It’s a staggeringly hot day in California’s San Fernando Valley. Out on the street, amid the malls and palm trees, the entire desert suburb seems to ripple and throb under the morning sun. Down in the morgue of the Walt Disney Company, however, I’m trying hard not to shiver. Yes, that’s right – morgue.

“We keep the temperature at a steady 15.5C with 50 per cent humidity,” explains Fox Carney, the rather unsettling figure who has agreed to show me around this little-known facility. Plump and mustachioed, he is dressed entirely in black, aside from a jazzy purple tie and white Mickey Mouse gloves. The gloves serve an entirely practical purpose – more on that later – but you get the sense that he enjoys the look.

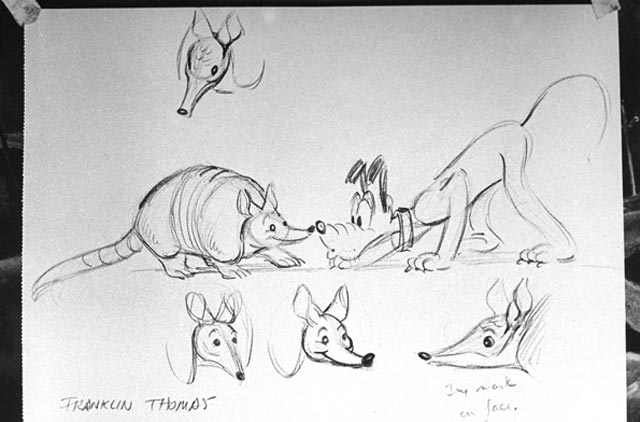

This isn’t any normal kind of morgue. The bodies kept here in refrigerated vaults are not those of terminated studio workers, but cartoon characters drawn in pencil and ink. They’re the rejects, the weaklings, the has-beens and the never-quite-weres... creatures who emerged stillborn from the imaginations of Walt Disney and the hundreds of staff illustrators who have worked at his company over the past 89 years.

Some of the artwork is signed, but much of it is not. A few of the drawings are on fast-food burger napkins, necessitating the services of a chemist who specialises in disposable utensil preservation. There are close to 65 million items in the building, a testament to the company’s foresight when it comes to guarding its intellectual property. No other animation studio in Hollywood has held on to its discarded scraps in such a way.

Disney has only recently undertaken the hugely expensive and painstaking task of digitising its archives for the on-demand age, however. Now, three years into the project, the company says this crypt of material – including drawings and storyboards featuring Mickey Mouse’s long-lost brother, Oswald, and a thwarted Second World War collaboration between Walt Disney and Roald Dahl – will be opened for all to see. The process began with the release of a video game, Epic Mickey, that has now morphed into a bigger budget sequel, Disney Epic Mickey 2: The Power of Two, and is likely to become a fully fledged franchise, complete with movie and TV adaptations. All of which explains why I have today been granted rare access to the Walt Disney Animation Research Library, as the morgue is officially known.

“When people come here, they often ask what all this is worth,” says Fox, as we enter a room with a giant table – an autopsy table, you might say – upon which are lost characters that in an alternative universe might easily have been as famous as Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck. “Our answer’s simple,” Fox says. “It’s priceless.”

Controversy and copyright

Anyone familiar with Walt Disney might find it surprising that the company is prepared to reveal its history in such a way. After all, this is an organisation that has been criticised – at times ridiculed – for its early output, some of which seems almost comically jarring to modern audiences. The website Cracked.com maintains a list of “The nine most racist Disney characters”, for example, and as recently as July, The New York Times accused the company of keeping its 1946 film Song of the South locked away “because of its idyllic depiction of slavery”.

Even today, Disney is loathe to discuss such controversies, but the hyper-sensitivity over its vintage releases is clearly diminishing. Perhaps it’s because the company no longer needs to prove its inclusiveness: its current line-up of star characters includes Tiana (an African-American princess), Doc McStuffins (an African-American six-year-old who wants to be a doctor, like her mother), and Phineas and Ferb (from a blended transatlantic family).

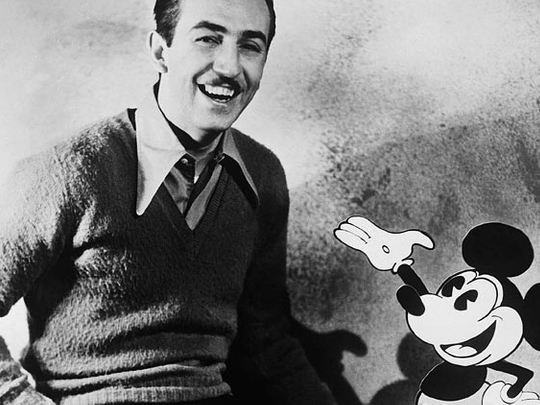

There’s another, more humdrum, reason why Disney has waited so long to exploit its past – copyright. Take Oswald. Walt created his “lucky rabbit” in 1927 after working on a series of films known as the Alice Comedies, starring a live action little girl – Alice – and a cartoon cat. Having no money at the time, Walt sold ownership to Universal Studios, only for his bosses to reject Oswald’s debut film, Poor Papa. Another followed, entitled Trolley Troubles, in which Oswald was upgraded to a younger, neater rabbit with a black body, white face and baggy dungarees. This time, the cartoon was a success, but Walt soon gave up on his creation because of money and control.

Oswald’s career continued for a while at Universal under the producers Charles Mintz and then Walter Lantz, but he suffered from a lack of creative direction, and, more importantly, Walt’s talent for brand exploitation. Before long, Oswald was an ex-rabbit. “It’s very possible that Oswald could have taken off in the same way Mickey Mouse did,” says Dave Smith, who founded Disney’s first archive in 1970 and has since written an encyclopedia of the company. “But Walt didn’t have access to him any more, so he couldn’t do anything. That’s why he had to come up with a new character; Mickey.”

For six decades, nobody gave much thought to Oswald. That changed in 2005, when Bob Iger was appointed chief executive of Disney, ending a tense and embarrassing period for the company during which its management fell out spectacularly with Walt’s relatives. Iger’s first move? After buying Pixar animation studios from Steve Jobs for £4.6 billion (Dh27.2 billion), he traded the ESPN sportscaster Al Michaels – along with a few broadcasting rights – for Mickey Mouse’s forgotten, long-eared brother. “I’m going to be a trivia answer someday,” complained Michaels at the time.

Oswald was back. Not only that, but Pixar’s chief creative officer, John Lasseter, had also started to take a keen interest in Walt’s early creation, along with the millions of other unused drawings kept in the morgue – which, by then, had moved location twice since its original home in the basement of the “ink and paint building” on Disney’s studio lot.

“John asked the question one day, ‘Hey, why can’t I see the Animation Research Library on my desktop?” says Fox, who manages the closely guarded facility. “That was three years ago. Of course, we’d been scanning things before then, for at least a decade, but not on an industrial scale like we’re doing today.”

Security and inhuman patience

With that, Fox leads the way through the rest of the building. The cold is getting almost as uncomfortable as the rules – no pens are allowed, photos must be taken at specific angles (so the artwork cannot be reproduced), and leaning too far over an image prompts an intervention by one of the many security guards. Skin contact with original material is not allowed, which is why Fox and most of his colleagues wear gloves.

There are 11 vaults in total, each filled by towering grey cabinets on rails, along with layer upon layer of rolling walls, upon which framed examples of the morgue’s secrets are hung. The latter are protected by UV curtains so heavy they could probably stop bullets. The work is familiar and strange, a lot of sketches were created for well-known Disney productions, such as Lady and the Tramp, but didn’t make the final reel. One particularly curious vault, meanwhile, contains films that were halted before completion, including My Peoples, about Abe Lincoln (alternative titles include A Few Good Ghosts), and Wild a Life, based on George Bernard Shaw’s 1912 play Pygmalion.

Although thousands of these items were catalogued under Disney’s previous, antiquated library system, many more were not. “Each month we get another pile of undetermined artwork, and we have to figure out where it came from,” says Fox, as we enter a hangar-sized darkroom in which technicians use a gigantic 240-megapixel camera (to put that into perspective, pro photographers’ cameras rarely have more than 25 megapixels) to photograph decades-old illustrations one by one, which then appear in crude animated sequence on an equally huge flat-screen display.

The process looks exhausting. The camera takes pictures in such detail, it takes two minutes for the shutter to open and close. Yet the effect of seeing a stripped-down, 57-year-old sequence from Lady and the Tramp come to life in such a way – there’s no backdrop, just a pencil-drawn dog on aged white paper – is quite beautiful, as though the ghost of the illustrator were in the room. In the bottom right corner of each image, meanwhile, you can make out the original, meticulous frame-numbering system; a reminder of the almost inhuman patience required back then to make such a film.

A second chance at fame

When the digitisation of the morgue began, the enviable – if intimidating – task of choosing which creatures to exhume came down largely to one man; Warren Spector. A grey-bearded video-games designer from Austin, Texas, who wears brightly coloured bowling shirts and a Mickey Mouse watch, Spector’s solution was to set the Epic Mickey games in a dystopian universe known as the Wasteland, which he describes as “a repository for all Disney’s forgotten, discarded stuff: the concepts that didn’t make it, even the Disneyland rides that have been shut down”.

Oswald, unsurprisingly, is the hero of this world – albeit an Oswald who is improved in every way, from the 3D roundness of his face to his more elastic limbs and more sophisticated backlighting. As for the rabbit’s personality, “We had to come here to the archives to find out who he was,” says Warren, grinning.

From the early storyboards and drawings, the game designers quickly deduced that “he’s lovable, naive, a little too trusting, a force of anarchy... and of course very lucky, so he can get away with anything.” Until Epic Mickey, Spector hadn’t designed a children’s video game – he’s best known for the cyberpunk titles System Shock and Deus Ex – but Disney reassured him that it was happy with the characters from the morgue being darker than usual. The old rule for Mickey – that he’d never be “less wholesome than sunshine” – wouldn’t apply.

Spector takes me back to the autopsy table to demonstrate what he means, pointing out the storyboard produced by Walt Disney and Roald Dahl during the war for an adaptation of The Gremlins. “They worked on it for a year or so, but had trouble making these destructive characters who sabotaged RAF aircraft very likeable,” he reveals. The film was never made.

Spector, of course, doesn’t care about likeable. Hence the gremlins’ prominent role in Epic Mickey 2, alongside the Mad Doctor (a diabolical scientist who appeared briefly in a 1933 Mickey film) and the Phantom Blot (from a 1939 comic strip – “one of the lamest villains in Disney’s history – but now we’ve done something interesting with him”).

The rest of the cast is made up of the rejected versions of better known characters. “The dwarves, for example,” cites Spector. “Even Tinker Bell. Look!” – he walks excitedly to the other side of the table – “Here’s a new kind of version of her. Wow, she looks kinda like a combination of every famous 1940s film star who ever lived!”

Finally, there’s Ortensia, who appears as Oswald’s “steady gal”. She’s based on Sagebrush Sadie, a cat whose brief career involved starring in a deeply obscure short film released by Disney in 1928. Some claim that Sadie later inspired Minnie Mouse, but it’s debatable.

To Spector, however, the point of reviving such characters isn’t to establish or analyse their place in history; it’s to allow them to climb out from their tombs and get another shot at fame.

“I actually think Oswald’s a little resentful of Mickey’s success,” he laughs, before we head back outside, the tour over. “When you consider that as a foundation for a story, it’s almost Biblical, or like Homer – two brothers, fighting for attention.”

He catches the ridiculousness of what he’s saying. “I mean, OK, it’s about a mouse and a rabbit,” he adds. “But it’s also about all of us.”