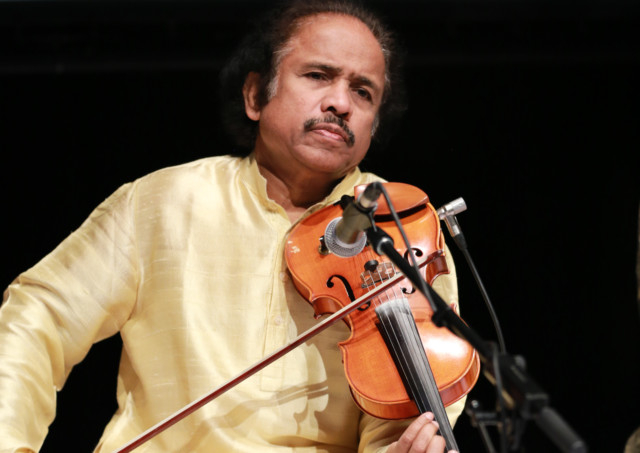

The calm composure and the placid voice of Dr Lakshminarayana Subramaniam is a bit of a deception – when his violin unleashes a relentless gust of melody in the quickest conceivable tempo and his fingers glide between notes in a tempestuous burst of agitation, you wonder whether this is the same person who spoke so sedately about the music he was going to play.

That powerful virtuoso performance was on display at the Dubai Community Theatre and Arts Centre (Ductac) on Friday night, when Dr Subramaniam returned to the city as part of the third season of Emirates NBD Classics — a series of monthly musical concerts designed to showcase a wide variety of classical traditions and their exponents.

A legendary violinist from the south Indian Carnatic tradition, Dr Subramaniam is equally at ease playing the instrument in the Western style, apart from being a conductor and composer who has dabbled into films – scoring the music for Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay and Mississippi Masala and performing as a solo violinist in Bernardo Bertolucci’s Little Buddha. A trained doctor (he earned an MBBS from Madras Medical College and registered as a general practitioner before giving it up to pursue music), Dr Subramaniam’s career has also seen him collaborate and perform with global music maestros as diverse as George Harrison, Yehudi Menuhin, Stanley Clarke, Stevie Wonder, Herbie Hancock, Jean-Pierre Rampal and Zubin Mehta.

But his Dubai concert, where he was supported by his son and violinist Ambi Subramaniam, was all about the celebration of Carnatic music.

The highlight of the evening was the violinists’ exquisite rendition of Kalyani, one of the most popular ragas (the melodic foundation of Indian classical music) as well as a parent musical scale in south Indian music. Following a leisurely exposition of the raga, Dr Subramaniam and Ambi worked towards a fitting finale in 16 beats, displaying throughout the traditional melodies and complexities of Carnatic music with sublime finesse. The duo often returned to the core melodic mode and employed it as a refrain, improvising on the taal (rhythmic pattern) as they delved deep into the heart of the cadence.

The second composition stood out for the brilliant interplay between the accompaniments – the mridangam (a double-headed percussion instrument), the tabla played by Pandit Tanmay Bose, the ghatam (a narrow-mouthed clay pot used as percussion) played by T.N. Radhakrishnan, and the morsing (a south Indian jaw harp) played by G. Satya Sai – with the violin duo joining in for the beginning and Ambi capping the coda.

Unlike its Western counterpart, Indian classical music thrives on the improvisation of ragas and taals, and such improvisations could take anything from a few minutes to a few hours to accomplish, depending on the synergy and the mood of the artistes. It was thus quite disappointing when the curtains came down on the concert after only three compositions and about 90 minutes of performance.

However, barring the odd issues with the audio output (perhaps balancing the right intonations between the electronic drone box and the acoustic instruments proved a tad difficult?), this was a night of soul-stirring music by one maestro at the height of his power and another in the making.