In March, international pop icon Pharrell Williams released the album GIRL. Now, he’s opened a new exhibition at Galerie Perrotin in Paris with the name, which is meant to engage with gender and its standing in the art world. Williams and gallerist Emmanuel Perrotin have known each other for eight years, but this is the first time an exhibition has come out of their partnership.

The show claims to “celebrate women who are, above all, free, liberated by artists and their boundless, unfettered imagination”. And there are some powerful and empowering pieces. Those include works by Cindy Sherman (a 1982 C-print self-portrait in which she’s draped in pink terrycloth), Marina Abramovic (posed with artist Ulay in a still from their performance, in which a bow loaded with an arrow is pointed at her heart), Yoko Ono’s 1964 Cut Piece (a still from her performance in which she invited the audience to snip her clothes off), and Sophie Calle’s The Breasts (a black-and-white self-portrait that shows her naked chest, accompanied by a text about her late development). Each is a maestro of the art world; each artist’s work is commanding, stunning, and makes sense in the context of an exhibition that intends to examine feminine identity.

But the show fails otherwise in so many ways. Ashok Adicam, senior adviser at the gallery, notes of the ratio of just 18 woman artists to 19 men: “It’s almost perfect parity between men and women artists, minus one woman.” A symbolic statement: almost-perfect parity is pointedly not parity.

Some of the artworks confront this knottiness head on. The collective Guerrilla Girls tackle the issue most explicitly, with graffiti announcing discomfiting statistics: “Less than 4 per cent of exhibited artists are women but 76 per cent of nudes are female.” Agns Thurnauer’s painting is a none-too-coy restructure of patriarchy, in which a reproduction of Courbet’s The Origin of the World is plastered over with feminised names of French male artists (Francine Picabia, Jeanne Dubuffet, Eugnie Delacroix). Artist Dan Firman’s Caroline addresses female marginalisation with a startling sculpture of a woman propped against a wall. Her silhouette is burrowing facelessly on to a piece of green fabric, as if she’s ducking for cover or being punished: words that certainly encapsulate the female experience in art for much of history.

There are also pieces that say much less about female identity than about the showmanship of putting an international pop icon on the masthead. Rob Pruitt’s Ikea couch graffitied with Pharrell doodles, or Daniel Arsham’s Future Pharrell sculpture based on a mould of the man himself, are nothing more than shrines. They are the GIRL of the album, and it’s a shame the two concepts get muddled.

But the real shame comes in the form of a Terry Richardson photograph. The image is a slice of girl shown from belly button to upper thigh, a chocolate heart covering her modesty with the words “Eat Me” scrawled in pink. Even if one were to repress the allegations that the photographer is a loathsome sexual predator, the image is a baffling inclusion.

Perhaps it was a purposefully incendiary choice? Apparently not. “Terry has been a friend of the gallery for a long time,” Perrotin says breezily during a tour of the show. “We could have selected an image that is, how can I say this, ‘easier’, less ‘ambiguous’ ... this is a vision of women that exists, and is represented. He’s a photographer that’s very important.” He continues: “We’re behind him. He’s a very good guy.”

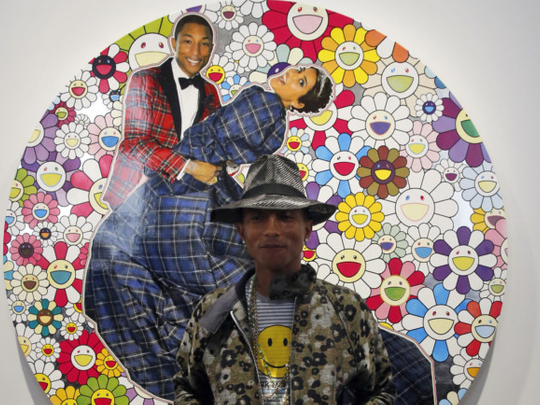

At the press opening, I confronted Pharrell about this. Wearing a large hat that now sums up his whole style, plus a smiley-face T-shirt, he was personable and deferential. “He has his own expression ... What we were trying to accomplish with this project was to house many different facets of women,” he said. “This was meant to be a democracy, where people could contribute their views as long as we didn’t see it as being outside of what we were trying to do ... We want people to talk about these issues; we want to spark conversation.” Then, peculiarly, he continued: “Just because you’re a good girl doesn’t mean you don’t have naughty thoughts” — as if naughty behaviour were somehow in question, rather than misogyny. (The issue was all the more complicated because, in fact, Richardson was Pharrell’s wedding photographer). Perrotin’s tone differed: “I saw [Terry Richardson] on many occasions doing photoshoots, and it’s a real big party all together; I promise you the woman part of the photoshoot doesn’t look a victim of anything.”

After the press conference, Pharrell approached me to say he appreciated my question. Perrotin approached me mere moments afterwards to tell me the Richardson allegations were fabricated.

It’s one thing to talk about how women are portrayed, but it’s another when you contextualise that. As Perrotin himself said, his gallery represents 17 per cent woman artists — an upgrade from the recent 14 per cent. (“We’re getting better,” he said proudly). This means that, from among 83 per cent of male artists — and 100 per cent of all artists possible — this was a selection deemed worthy of representing women, and generating conversation about women. Richardson’s picture not only depicts women in a demeaning way, but is taken by a man accused of abuse and intimidation in real life. For GIRL to include this is all the more absurd in the light of the proclaimed “almost-perfect parity”.

The incredible artists in this group show deserve their dues. But it is a bewildering, heartbreaking blindspot that Richardson is deemed worthy of inclusion. Curation is above all concerned with choices of taste and representation, and including Richardson undercuts any constructive narrative the show could bring to a much needed spotlight of the role of women in art. There can be no progress in the art world when resting on work full of misogyny shoddily disguised as provocation.