Modernisation is a violent process. Settled forms of existence are uprooted, ancient beliefs are abandoned and familiar hardships give way to unknown dangers. But risks also bring opportunities. India's post-independence settlement was paternalistic socialism — the state discouraged vulgar capitalism and the people remained untouched by material ambitions — that is, they stayed poor. Few got rich except gangsters and politicians.

In the past 20 years, though, there has been an explosion of free-market capitalism. Foreign companies such as Coca-Cola, once banned, are now welcomed. The growth of call centres, computer technology and car manufacturing has seen the country become the world's third-largest economy. The "million mutinies" V.S. Naipaul saw stirring in his 1990 book about India are now a billion and counting. In The Beautiful and the Damned, Siddhartha Deb has taken up Naipaul's mantle.

Five scenes from the new India are subjected to his sharp yet sympathetic eye. The central chapters about engineers, farmers and factory workers contain the most startling facts: In 1997 an Indian sold Hotmail to Microsoft for $400 million (Dh1,468 million); between 1995 and 2006, 200,000 farmers committed suicide, mostly by drinking pesticide; 77 per cent of the population live on less than 30p a day.

But the book comes to life with the character sketches in the opening and closing chapters. For his portrayal of India's new rich, Deb chooses the management guru Arindam Chaudhuri. The author of the (apparently) bestselling Count Your Chickens Before They Hatch, who sports a scraped-back ponytail and a cheesy smile, runs a business school for those unable to afford elite business schools. As he tells Deb during the five-hour monologue at their first meeting, he had little business experience when he put on his first leadership workshop. Nonetheless it was a "super-success". Chaudhuri is ripe for mockery, but Deb admires his audacity. For the lower-middle classes who attend his seminars, his high-pitched voice and nervous manner are reassuring signs he is one of them. He also drives a Bentley Continental, but the duality is part of his appeal.

Born in a small town in northeastern India, he worked at a magazine in New Delhi and now lives in New York. His humble origins allow him to gain the confidence of the low-paid factory workers and struggling farmers he speaks to.

Esther, the book's final subject, is also from the northeast. She has moved to New Delhi, where she works at a fancy restaurant called Zest. After a two-hour journey to work, she puts on heavy make-up and arranges her hair into the shape of a Z. Twelve hours later she makes the long journey home. Northeast women are prized in India for their light skin and good English. This also makes them vulnerable to exploitation. But Esther's disappointments are the everyday sort. She quit her old job at the Shangri-La Hotel when they forced her back to work soon after a road accident. Zest is pretentious and tiring but she gets good tips. On her urging, her boyfriend moves abroad to earn money, and then cheats on her. For a while Deb's confessional meetings with Esther verge on the romantic. But while she considers returning to her village to become a teacher there is little chance he will return to live in his hometown. Global capitalism, though it brings suffering, has given Deb the chance to become a metropolitan writer. And if his voice in the book sometimes shades into that of a campaigner rather than an observer, it is because he feels uneasy about publishing a beautiful book about the damned he has left behind.

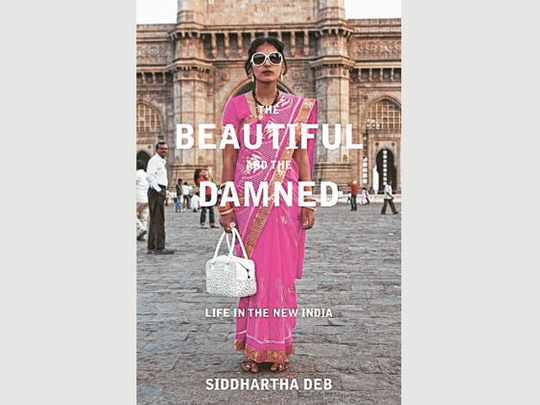

The Beautiful and the Damned: Life in the New India By Siddhartha Deb, Penguin, 253 pages, £14.99.