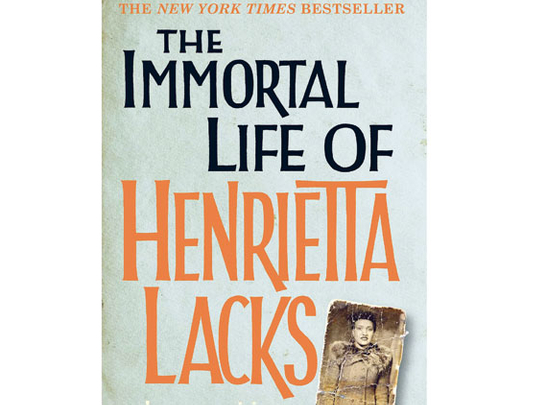

Unless you are a scientist, you have probably never heard of Henrietta Lacks or HeLa cells. The fact is, her cells could have helped conceive your firstborn, protected your children against polio or cloned the first sheep.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by first-time author Rebecca Skloot aims to lift the anonymity behind the cells, which have been used for decades in scientific research, with great advance.

Right from the start, the book is gripping — firstly the premise is fascinating, and as the story develops, the poignant story behind Henrietta and the suffering of her family is revealed.

Henrietta died of cancer in Baltimore in 1951. Before her death at 30, a tissue sample was taken without her knowledge or consent and became the first cells to be grown and reproduced in culture in a laboratory (hence "immortal").

The cells were sent by the scientist at Johns Hopkins hospital, George Gey, to other scientists for research purposes. Since then, the cells have been used in research around the world, bought and sold by medical companies making a lot of money on their "immortality". To date, the Lacks family has not received any money from the proceeds of HeLa cell sales and cannot even afford their own health care.

Before the days of any type of informed consent, members of Henrietta's family were asked to come to the hospital under the premise that they needed to be tested for cancer. Samples were taken from them and also studied without their knowledge.

Striking the right chord

Skloot spent 11 years researching and writing the book, which took her on sometimes traumatic journeys with the Lacks family, and around the United States.

Eventually she managed to convince the distrusting family to speak to her about Henrietta, to discover what happened to her cells and what happened after the "immortal" discovery was made.

Suffering from ill-health, Deborah Lacks — Henrietta's daughter — accompanied Skloot on many of her research trips. The discoveries made on one of these trips almost gave Deborah a stroke.

One of the reasons that the story is so captivating is that Skloot as a science writer takes on a role herself in the book akin to a detective.

The science-writer turned detective makes unbelievable discoveries in her search for the truth behind HeLa; sometimes shocking, poignant, horrifying and upsetting at the same time.

The story becomes more about Skloot's journey to finding out the truth about Henrietta than about Henrietta herself — admittedly having died at 30, not much actually happened in her life.

It also raises ethical questions about tissue sampling — there is not yet any kind of consensus or regulation on informed consent for patients. Henrietta's cells were taken without her knowledge or consent and used by scientists who made great discoveries. In one case explained, a man's spleen was removed (because of disease) and thereafter used in research without his knowledge. When he found out that his tissue had been used to the advantage and great profit of medical companies, he took the case to court. He lost the case as the judge deemed his spleen to have been "waste" as it was diseased and therefore removed. This raises another question about whether tissue samples taken and tested in research are still the property of the person after they have been removed.

Skloot explains the science behind HeLa well, making the most complicated, scientific parts of the work easy to read and understand — even for those uninterested or unknowledgeable about science and its complexities.

Although Henrietta died decades ago, her cells and the ongoing debate about informed consent make the book relevant today.

The tale is wracked with tragedy and injustices done to the Lacks family who still struggle on low incomes. It is an unbelievable true story, which is a product of intense research, hard work and determination on Skloot's part.

Skloot takes the reader on her journey — and the journey of Deborah Lacks — with great finesse and honest representation. It ends with sadness but also hope for the Lacks family, after Skloot herself set up a foundation for Henrietta's descendants.

She has also established an education fund, both of which readers can donate to via the internet.

With HBO and Oprah Winfrey taking steps to make a film of the life of Henrietta Lacks, Skloot has ensured that this very important woman — with famous cells — will become known, respected and thought of not only among scientists, but around the world.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks has been on The New York Times and Los Angeles Times bestseller lists.