When Nermine Hammam pushed her way through the crowds into Cairo’s Tahrir Square, five days after the occupation had started, she found people dancing, smoking and playing music.

“I hadn’t known what to expect,” she says. “The jokes were fantastic, the slogans were so creative. I was amazed and I was emotionally moved — but I didn’t trust. In my mind there was always a doubt about what would happen next.”

The photographer and visual artist had been in France for an exhibition of her work when the square was occupied in January 2011. She recalls: “I turned on the American television and it said ‘democratic revolution in Egypt’. I turned on British television and it was ‘democracy, maybe, perhaps. We’ll see what’s going to happen.’ On Iranian TV, it was like an Islamic revolution was happening. Then I turned on Egyptian television and there was a film. It made me realise that you see what you want to see — there’s no reality to anything.”

She has gone some way to identify her own, very individual, sense of reality with 70,000 photographs she took during the Tahrir revolution, a selection of which are on display in her first exhibition in the United Kingdom, “Cairo Year One”, held at the Mosaic Rooms, a centre for Arab culture, in west London.

But it is what she has done with that selection which lifts the exhibition out of pure reportage. Using a mix of Photoshop, her design skills and knowledge of film to subvert the original images, she has created two series of works — one entitled “Upekkha”, the other “Unfolding” — which investigate what constitutes the reality of those heady, violent days.

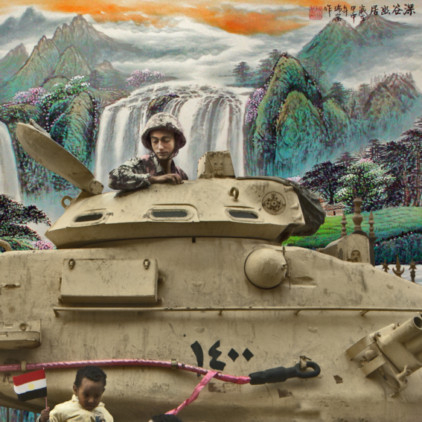

“At first, the surprise to me were the soldiers,” she says. “They were wide-eyed youths, showing a mix of military tenderness, virile coquetry and masculine frailty, not so much heroic but young and effeminate. They were just poor boys, with backgrounds as deprived as the protestors around them. They became almost domesticated, with their military vehicles used as climbing frames by children or with washing hanging from their tank gun barrels.

“It dawned on me that power is a myth — a perception bolstered by its images. In the square it was as if it was the protestors who were conferring power on the soldiers by letting them coexist with them. For me, it proved the terrible frailty of power.”

In “Upekkha”, which is a reference to the Buddhist ideal of equanimity, Hammam parodied the “masculine frailty” of the troops by replacing the setting in the square with a backdrop of postcards showing mountains, waterfalls and verdant landscapes.

“They were like the propaganda posters from the 1940s and 1950s which feature strong men and young women in idealised settings,” she explains.

We see smiling lads gesticulating amiably at the camera against the backdrop of a lake; two soldiers taking a break, spooning up a snack while standing in a field of flowers with white peaks in the distance; a sweet-looking boy in a tank staring incuriously at a child with a flag while a waterfall cascades behind him.

“I have always collected postcards. Some are 50-60 years old and many have poignant letters on the backs. Somewhere in my subconscious, the idea had developed of using the cards to emphasise the discordant presence of armed men among civilians. It was as if they were men of war in the paradise of Tahrir,” Hammam says.

Much of her work is influenced from her time working in film in New York and by her passion for cinema —“People make fun of me because I watch a film every day come rain or shine”. But she has also spent many years running a branding company for shops and restaurants in Cairo. “Commercial knowledge gives you an edge on technicalities,” says Hammam, who was born in Cairo in 1967 and had her first exhibition, on the scenes of the city’s religious festivals, in 2001.

Not that her work is remotely commercial. Her most striking works include “Metanoia” (2009), a photographic essay of patients in a Cairo mental asylum, which the Ministry of Health censored heavily, and the surreal “Anachrony” (2010), which depicted two figures wrapped in massive sheets of coloured cloth in desert landscapes. “Each project is important because you learn something,” she says. “You remove a layer every time.”

What characterises her original photographs from the square is their immediacy. “I was very careful to take them as snapshots, not iconic images,” she says. “The whole idea was very important to me because the square was full of people with their phone cameras and that was very equalising.

“I didn’t care about the cropping because I could not wait for a person to talk to me like I did in the asylum piece. Everyone was rushing about or hanging out, but definitely not waiting to have their picture taken. I did have some which were well composed but I discarded them. It was done with a certain abandon and for that I was much freer. I just wanted to catch the moment.”

But that moment of euphoria turned to despair — as she captures in the second set of pictures, “Unfolding”, which was compiled a year later.

“At the beginning, I felt safe when I entered the square because we were all united in one cause, which was to get rid of that one man,” she says — the name Mubarak was never mentioned in the interview. “The night, that one man let all the chaos break loose. Women were molested and the troops turned violent with truncheons and tear gas.

“We were bombarded with images of the violence from Reuters, AP, all the agencies and newspapers. You know, you could be sitting in the pub and there would be a scene of violence in front of you but then, because it is all happens in an instant, it is quickly forgotten or taken for granted. So I thought, let me put those images in another setting and how would we see them?”

In “Unfolding”, she has superimposed those scenes on to Japanese and Korean screen prints.

“I cannot explain why I chose them,” she says. “I think it is because the screen allows distance and pulls back from the images of violence and death that filled our TV screens. A wall would just block out the picture but a screen is shadowy. They look pretty and have a formality that contrasts with what is going on behind them so you have to look very closely to really understand what is going on.”

She adds, “It is as if the ambiguity emphasises the pain of the reality” — the infamous picture of a young woman being dragged away has her assailants partly obscured by flowers; a visored soldier, baton in hand, attacks a man huddled on the ground while storks stalk past, stately and poised; a clash in the square, in which the soldiers are dismantling a small tent city, is superimposed on a silk screen of the Korean Choson dynasty, its fluttering birds contrasting with the angry faces.

Now, that niggle of distrust which struck her when she first visited the Square has been confirmed. “That sense of unity has drained away. Women wearing dresses or going out not covered with the niqab are being harassed. I don’t know by whom, maybe Muslim extremists or a political faction which is following some Islamic doctrine,” she says. “Disillusion was expected. The army is behind the violence. Maybe they were part of the coup right from the beginning because he [Mubarak] was the leader of the army and they did not want his son to take over.

“Now I think it depends which side you are on. The non-Islamic side is extremely apprehensive while the ones with Islamic sympathies are ecstatic. But that is what the core of my work is about; everything is fleeting — so what is reality, what is the moment? Reality is subjective. There are many gods. Look at India, where they have a thousand gods. What I learnt from the mental hospital is that if you have a nervous breakdown or get hit on the head, your whole reality changes.”

Will the reality, as conjured up in her pictures, ever be shown in Cairo, or will her work be censored once again? “I don’t know,” she says. “The pictures are a bit shocking for Egyptian men. A man would not have taken those pictures because it hits you somewhere, but as a woman I just zoomed into situations that traditionally are not allowed for women.”

People would ask her, “How could you do this?” Her response would be: “But I didn’t do anything. I didn’t make them pose like that.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

Cairo Year One will run at the Mosaic Gallery, Cromwell Road, London, until August 28. Three works from the Upekkha series will be shown as part of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Light from the Middle East: New Photography from November 13.