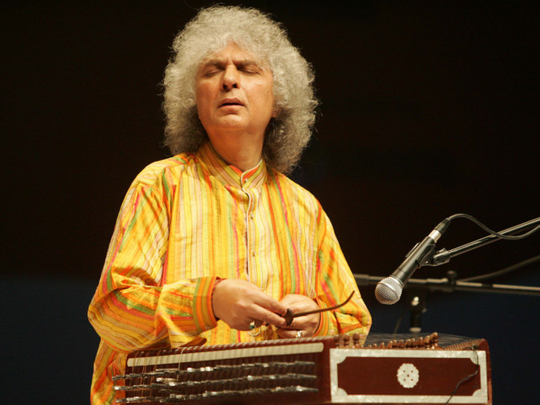

Performing on the world stage for six decades, Pandit Shivkumar Sharma is not just a renowned musician, he’s also the pioneer of an instrument that was thought unsuitable to play Indian classical music: the santoor.

“I played the tabla professionally for a long time. My father Uma Dutt Sharma was a versatile musician and a performing vocalist. He taught me to play the tabla,” Sharma told tabloid! “I used to accompany musicians such as Pandit Ravi Shanker, Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, Siddheshwari Deviji, Begum Akhtar and others when they came to perform at Radio Jammu & Srinagar in the early 1950s. And then came a time when I had to decide between the tabla and santoor.

“My father — my guru — had a vision and I believed in him. It wasn’t easy for me to establish the santoor as there was a lot of scepticism — critics said it was impossible to play classical music on this instrument. He used to tell me: ‘One day, your name will be synonymous with the santoor. And here I am today”.

Sharma will perform at Ductac in Dubai on Friday as part of the Emirates NBD Classics II series, accompanied by Bhavani Shankar on the pakhavaj, an ancient percussion instrument used in the Drupad style of music, Ram Kumar Mishra from the prominent Benaras gharana on the tabla and Dilip Kale, one of Sharma’s senior santoor disciples, on the tanpura.

When tabloid! asked Sharma on what new he would bring to the stage as he’s been a frequent performer in the city, the maestro laughed.

New experience

“The beauty of Indian classical music is that it is not planned or rehearsed. Yes, there are timings of the raagas [melodies] but we use no written words or notations. So, even if it is the same artiste performing or the same raaga being sung, it’s always a new experience”.

Sharma believes that the audience for classical music has increased tremendously in the last 60 years, though the knowledge of the genre hasn’t.

“In the 1950s, the number of classical music listeners was much less. Exceptions were there, such as in Kolkata where we performed to packed halls with less than 1,000 people and speakers were placed outside so people on the road could listen to us. Moreover, the average age of a listener was over 40, who were more knowledgeable about the intricacies of classical music.

“Today, music festivals such as Bhimsen Joshi’s Sawai Gandharva in Pune attracts 12,000 to 15,000 people, with a lot more younger faces. Yet, 90-95 per cent of them don’t know classical music at all, they simply enjoy listening to it”.

He, however, agrees that santoor is a more difficult instrument to learn to play as compared to other stringed instruments such as the sitar or veena.

“First of all, there are 100 strings to be tuned. Secondly, santoor is a comparatively young instrument to other stringed instruments such as sitar, sarod or veena, even though we’ve found mention of it in ancient scriptures: the shata tantri veena [the veena of 100 strings],” Sharma added. “It was only used in Kashmiri Sufi music. Today, no classical music festival is complete without it, inside or outside India. I’m sometimes surprised about its popularity.

Transcending genres

“If we are talking of evolution, it’s in the music created by it rather than the instrument itself. It has crossed over from classical to world music. My son Rahul Sharma, who is a pure classical musician, has given a new dimension to it. Rahul’s compositions have been played by Richard Clayderman, the renowned pianist, and he’s also collaborated with Kenny G, the saxophonist. But if you wish to learn it as a hobby, it’s definitely difficult”.

Sharma has also dabbled in Hindi film music with legendary flautist Hari Prasad Chaurasia, composing for the late Yash Chopra’s films such as Silsila, Chandni and Lamhe. He agrees that the classical element is missing from Hindi film music, yet feels it’s a question to be answered by the filmmakers.

“This is feedback I get from many. I’ve worked with a director like Yash Chopra who had such great taste in music and poetry. We used to be told: ‘This is my location: Amitabh Bachchan and Rekha are in a tulip garden in Holland and then in the next scene, they’ll be in Kashmir. I want music to suit that’. And we created music keeping that in mind.

“What we see today is also the director’s concept and liking — probably the kind of films being made require that kind of music. I’ve been told that some directors have asked composers to create tunes that sound good as a cellphone ringtone. If the director demands that, then that’s how the music will be”.