A flock of snow-white cranes in flight, cherry trees in full bloom, elegant women coyly smiling behind hand fans ... these are all designs on a kimono! Shalaka Paradkar meets the Englishwoman whose exhibition of exquisite kimonos in Dubai was a delight

It isn't everyday that a section of a popular mall is made up to resemble the wardrobe department for Madam Butterfly.

It was a special time of the year for sure - the rainwashed air smelled clean, there was a sense of freshness all around, and scores of kimono, suspended from wooden frames, fluttered merrily creating a resplendent art gallery of silk and gold.

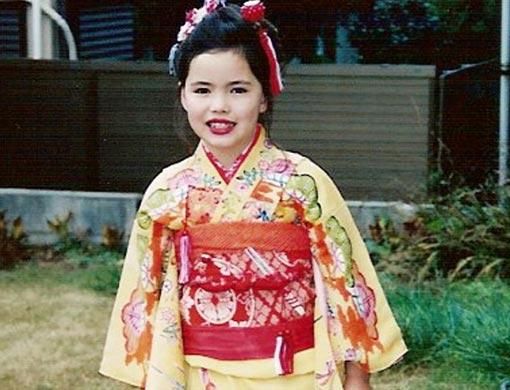

The famed Japanese minimalism was conspicuous by its absence - this was a riot of colour; lush, decadent and absolutely exotic.

Chrysanthemums were abloom, village brooks were gurgling, snowy white cranes were taking wing, elegant women were fanning themselves in gardens that were bursting with flowers in a profusion of colours - from eye-popping saffron to muted greys to bright magentas to soft blues.

These kimonos had never before been seen in the UAE. They were the private collection of Sheila Cliffe, an English textile artist now settled in Japan, and were on exhibition at the BurJuman mall as part of its recent annual art event, Art and Fashion 2006.

Cliffe, a graduate in art and drama from Roehampton Institute, London University, first visited Japan as a student in the summer of 1985. She was there to study shintaido - a martial arts form a bit like karate - during her summer vacation. But so deeply did she fall in love with the country that she decided to stay on for a few years.

"I have continued to be in love with the country and the culture to this day,'' says Cliffe, who enjoyed exploring the mountains of Japan with some friends "and a small pocket dictionary".

It did not take long for the British lady to fall in love with the splendid costumes of the land of the rising sun that she signed up for a textile dyeing class and another on kimono dressing. She also honed her Japanese language skills on the job.

Cliffe then went on to study the art of kimono dressing and qualified as a kimono dresser and teacher.

Cliffe's love affair with kimonos was sparked off by her visits to flea markets to look at pottery, another of her passions. "I almost always found a rack of old kimonos and innerwear there," she reminisces.

"I was absolutely captivated by the bright red silk of what I thought were some plain kimonos. I bought one and then someone told me it was innerwear. It is a good thing I didn't wear it outside! I was amazed by the gorgeous fabric. I became fascinated by the kimono ... and all the wonderful textile decorating techniques that you cannot see in the West."

A kimono requires about 12 metres of cloth that is 36 centimetres wide. It is wrapped around the body and belted at the waist with a wide sash called an obi. Kimonos vary in their material, patterns and motifs, and the width of the obi. A kimono is hand-sewn in straight lines, with no cutting or shaping.

There are many fascinating aspects to a kimono. What Cliffe loves the most are silks and ancient Japanese designs. "It's not just about whether (the material) is thick or thin,'' she says, adding there is a lot of thought that goes into the making of a kimono.

"Japan's clear-cut seasons inspire the designs and themes. Pattern, material and the lining cloth reflect the season in which the kimono is worn. So you have spring kimono, summer ones that are unlined, autumn and winter designs ... ," she says.

A full formal set of kimonos and accessories will include about 20 different pieces, which again can be coordinated in many ways.

Many of the fabrics for kimonos are, to this day dyed and woven by hand - a process that can take months, says Cliffe. "They are all handsewn, respecting the traditional techniques. Also, a high value is placed on the work of the craftsman.

"It takes longer to get dressed (in a kimono) - so I feel good about myself when I wear one. (When I am in a kimono), I take care about the way I move or speak. It makes you feel more feminine. It can also be very alluring, without being revealing."

Cliffe has the rare distinction of being the first non-Japanese to graduate from a kimono school.

"At first (the Japanese students) were wary of me. I, (too felt) strange being the only foreigner in the class. I attended classes for two hours a week for two years. Soon my classmates and teachers realised I loved kimono as much as any of them, and sometimes they went out of their way to help me.

"There are many special words to learn as part of the course, and that was very difficult. Also, you are expected to learn by watching, and I am the kind of person who always wants to ask "why?", so compared with the Japanese girls, I was a noisy student."

At the final test at kimono school, which she had to pass to become a qualified dresser and dressing teacher, she took pains to memorise long passages of text and repeated them correctly.

"This was really hard, as I had to remember so many difficult words. I also had a take-home written test about designs, kimono care and so on. Then I had a final dressing test where I had to dress a model and tie an obi beautifully within 15 minutes. Everyone practised really hard for that."

Cliffe has been collecting kimonos for 18 years, and has about 150. Not all of them made the cut for the exhibition, though. Also, there are many different styles that she is still to include in her collection. Some of the finer examples of kimonos of different weaves are very expensive.

Like most collectors, Cliffe trawls antique and junk shops, flea markets and any place where she hopes to find kimonos. A few have been donated to her by friends and a few people who saw a television programme about her work.

What's amazing is that she has rarely bought a new kimono for her collection. Most of them have either been sourced from flea markets or given to her by friends and well-wishers.

One of her favourites belongs to the Taisho period of the 1920s, when kimonos were so bright they verged on the gaudy.

"I love the outrageous colour schemes and big designs that were used (during the period). I have a few. They are popular now and quite expensive. I also love the raw silk ones. They have a kind of knobbly and rough feel to them and can be worn on casual occasions."

The Dubai show also had a fine example of a kasuri kimono from her collection. It is in a very deep brown shade and has designs of cranes and turtles - symbols of longevity.

Each thread is tie-dyed individually, and the rich brown hue is achieved by dipping the threads in a certain kind of mud more than 40 times.

This brown kimono comes from an area of Japan called Amami Oshima, where the soil has a very high iron content. Dipping the thread in the mud of this area gives it the particular brown tinge. Quite simply, it is unique.

Another kimono that holds a special place in her heart came to her when she was in England. It was a family heirloom that was given to Cliffe by an elderly English lady named Joyce Yuki Ritson.

Ritson's mother met a Japanese language student in the south of England, fell in love with him, and got married. When Ritson was born, her father's relatives sent her a kimono from Japan. She lovingly preserved it for many, many years before giving it to Cliffe.

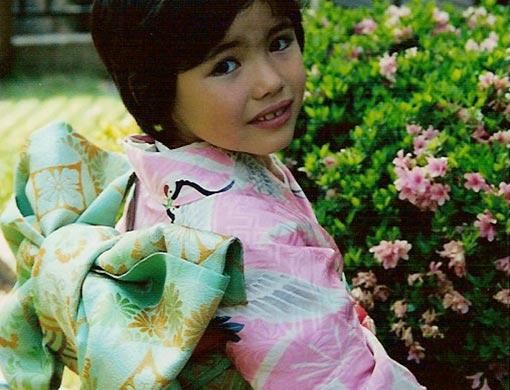

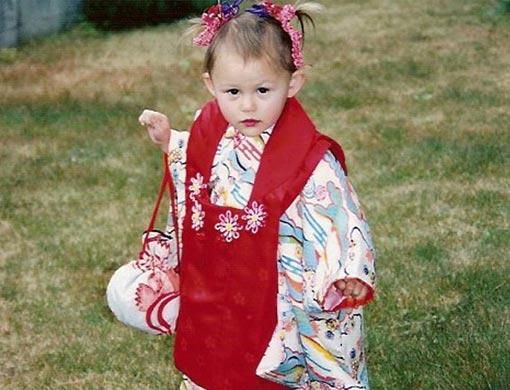

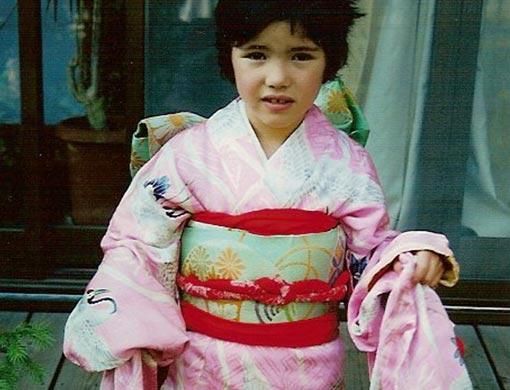

"That kimono is so very romantic. I put it on my daughter, but I don't lend it," says Cliffe.

Today, kimono wearing is on the wane. Yet Cliffe believes the Japanese will never say sayonara to their national costume. It is still the preferred garment for weddings and formal occasions.

"Unlike many national costumes though, it is difficult to get dressed in and one needs to take lessons on how to use it. Of course, this knowledge was handed down from mother to daughter until the (Second World War). The young girls of today, however, do not know how to use it. So there are kimono schools," she says.

The kimono has inspired many Western designers, as evidenced by the Memoirs of a Geisha-inspired

runway fashions a few summers ago. And in Japan, there has been a revival of the lightweight summer cotton yukata.

Cliffe says that woven, casual kimono are also now popular

as a choice for business or entertaining. Kimono are also sported by women who study other Japanese arts like flower arrangement or tea ceremony, and a certain section of waitresses and hostesses in Japanese clubs.

Cliffe's marriage to a Japanese man lasted 13 years (she is now single). "I think maybe he was unhappy with my busy and active lifestyle!" she muses. She now works at Jumonji Gakuen Women's University, in Japan, teaching English and also a little about kimono and textiles to Japanese girls.

Cliffe's kimono collection has been shown five times in the UK, with a different selection each time. One of the challenges has been finding appropriate venues: she wants to showcase it in London, but can't find a suitable gallery.

The Dubai show was the first time her collection travelled outside the UK. She now has her sights set on New York and Paris.

"It is still difficult to find people who want to put on the show. It attracted more than 3,000 people in a very small northern English town, but many galleries are still not convinced (about the kimono's popularity)," she says.

Cliffe's sister in England, Helen Stewart a nd Dr Graham Worth, of Manchester Metropolitan University, have played key roles in planning, arranging and hosting exhibitions.

Cliffe has three children.

"My two daughters have kimonos that I dyed for them, and they also love kimonos, especially my older daughter. My son, though, is just not interested," she laughs.

Little wonder that Cliffe describes her collection as a living one. "It is not dead in a museum. I wear the kimono, people wear them. I dress people in them. (Kimonos) are ambassadors of culture. Neither are they very extraordinary garments that normal people do not have. They have not been designed by great designers. They are the type of kimonos that people might have in their kimono chest at home."

Of the kimonos exhibited in Dubai, the most valuable piece was actually an obi woven using the tsuzure technique.

"Tsuzure weaving is done by hand and can only be performed if one of the nails of the weaver is cut into grooves through which silken threads are passed. It is a very exacting process," says Cliffe.

Apart from getting her kimonos to travel the world, Cliffe still has a couple of dreams she still wants to realise.

One is to do a doctoral thesis on the knowledge and feelings of Japanese about kimonos today to learn what craft techniques are considered valuable, and which ones will die out.

Thanks to the internet, the kimono business is changing dramatically, she feels.

The other dream is to share her knowledge of kimonos with others through a beautiful book. "Of course I would like to share some stories too, but it is essential that the book be published by a good art publisher who can render the kimono into a visual feast.

"Some publishers showed an interest in the project, but none offered to put up the money and make it actually happen. So it remains a dream."