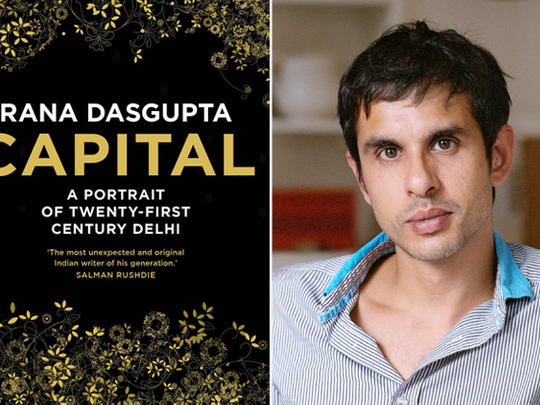

Capital: A Portrait of Twenty-First Century Delhi

By Rana Dasgupta,

Canongate, 512 pages, £25

In the final pages of this intense, lyrical, erudite and powerful book, Rana Dasgupta makes the most important of many perceptive points: there is no certainty, indeed little probability, that the city will eventually find the relative calm, order and hygiene of its counterparts in the developed world. There is no obvious reason why the evolution of this crowded, traumatised, violent metropolis in India in the early decades of the 21st century should follow that of New York, London or Paris in another place and another time. Delhi will remain as it is.

Judging by the content of the previous pages, this is a frightening prospect. Dasgupta has provided a welcome corrective to the reams of superficial travel writing describing the whimsical, the exotic, the booming or simply the poverty-stricken in India. His is a much more complex, darker story and it is no surprise that his book is peopled by the corrupt, the tragic and the terrified.

Dasgupta was born and raised in the United Kingdom and his work thus fits in a long tradition of nonfiction writing on India by outsiders who are also insiders.

The idea to take Delhi, and more particularly its new “bourgeoisie”, as a subject is a very good one. Through an unflinching portrayal of the arrogant, aggressive, ultra-materialistic new wealthy in the Indian capital he makes broad points about India a generation after the major wave of economic reform which unleashed a savage capitalism in the country.

“If I do something, I do it for myself, I do it for my family and I do it for my friends ... For nobody else,” says one interviewee, a hugely rich industrialist. Another, the troubled and driven scion of a big business dynasty, talks of the “contempt” he thinks he would feel for the workforce, who toil on the construction sites which make his family’s fortune. He “thinks he would feel” because he has not actually viewed their prison-like accommodation, with its filth, disease, danger and overcrowding. To these people, and many others like them, the poor are invisible, airbrushed out of reality.

But the book is more than a critique of global capitalism and India’s version of it. After all, Dasgupta’s talents are as a writer, a chronicler and an observer, not an economist. It is an investigation of the essential violence which underpins all relations in the city, that is the essence of the place.

Dasgupta traces this back to the destruction in 1947 of the erudite, spiritual, syncretic civilisation that united Muslims and Hindus in the city. There are many earlier traumatic events too — the razing of the city by a series of conquerors over a millennium — but it is the massive violence that accompanied the partition of British India, the exodus of so many Muslims, the influx of huge numbers of scared, stunned, bitter refugees from the Punjab, which defined Delhi’s dark soul. This marks, Dasgupta writes, “the birth of what can be recognised as contemporary Delhi culture. This is why the city seems so emotionally broken so threatening ... The residual trauma, like DDT in the food chain, became more concentrated with time.”

Delhi’s obsession with money, property, power and outward display is the “diametric opposite” of the detached, spiritual outlook of the city’s wealthy before 1947, Dasgupta says. Here, instead of meaning a celebration of community, the word “communal” indicates sectarian conflict.

The emasculation experienced by northern Indian men during partition, when women were subjected to atrocious violence, plays its role in explaining another significant feature of modern Delhi. In one of the bleakest passages in this bleak book, Dasgupta talks of the “low-level, but widespread, war against women whose new mobility made them not only the icons of India’s social and economic changes but also the scapegoats”. Independent women threaten a deeply fragile masculine identity and are punished, often publicly, as a result.

The gang rape and murder of a 23-year-old woman on a bus on Delhi’s streets in December 2012 marked an inflection point in the general narrative overseas about the city. The attention it attracted was due in large part to the previous perception of the city as the capital of a country that was “emerging”, a process which in the west is seen as a uniform and smooth ascent of hundreds of millions of people.

But change generates enormous tensions, which often lead to great violence. This is true right across south Asia. If major conflicts alive at the end of the last century such as those in Nepal, Kashmir or Sri Lanka have cooled, many others, at a lower level, have sprung up. These include anti-Muslim attacks in Myanmar, gang wars in the tiny island nation of the Maldives, the lethal street politics of Bangladesh, the criminals who kill in Pakistan’s Karachi, extremist groups on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, conflicts over land, water, mineral resources, caste and, increasingly, values in India. This is certainly an emerging region in economic terms. But it is also an extremely violent one. This does not contradict the growth story, but it is an inherent part of it.

Dasgupta’s unstated but apparent nostalgia for rural life — a feature of many critiques of the urban from both left and right wing — sometimes jars. There is nothing particularly bucolic about India’s villages, and urbanisation combined with industrialisation is almost certainly the only way that sufficient wealth can be generated for future generations to enjoy a better life. It is simply not the case that most people in India are worse off now than 20 or 30 years ago, as a glance at figures for literacy, life expectancy, maternal mortality and so on makes clear. Gains are grossly unequal, but real.

Perhaps this is clutching at straws. Dasgupta may well think so. His final warning is that Delhi as it is, not as it might be, is the future, and not just of India’s cities but of hundreds of others across the planet.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd