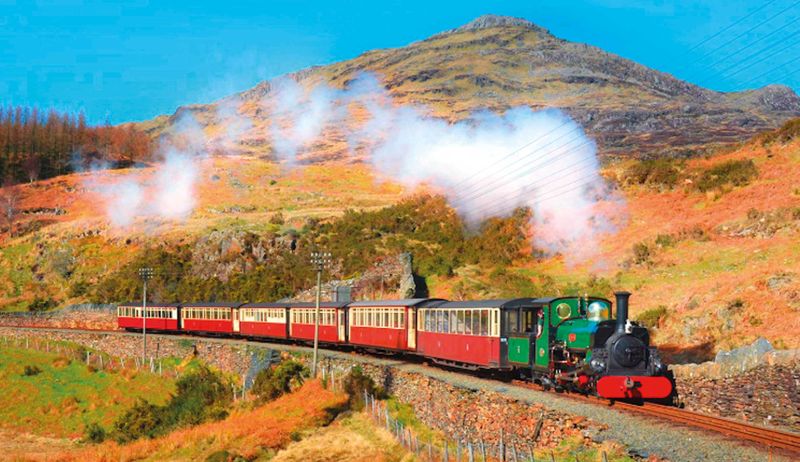

PORTHMADOG, WALES: With a puff of steam and a chuff of coal-fuelled smoke, the little engine seems to be breaking into a Victorian sweat as it eases forward on the track ahead.

This is Porthmadog, a small town on the coast of North Wales that sits at the head of a tidal estuary and fits snugly into the broad and deep shoulders of the mountains of Snowdonia – and it is railway nirvana for enthusiasts of little steam trains and tourists alike – or at least those who appreciate the oil and grease, coal and steam, engineering and signalling that still make the 170-year-old narrow-gauge railways function as they did in their working heyday.

The Festiniog Railway uses narrow tracks that are laid 59.7cms apart whereas regular trains up and down Britain use a much wider gauge, with those rails laid 1.435 metres from each other. The result is that everything is on a smaller, narrow scale.

John Greyfield from Chester, just over the border with England, is a retired chemist but is still awestruck by the alchemy that makes the Festiniog run almost like clockwork.

“She’s so beautiful,” he enthuses, focusing his camera on the finer points of the driving mechanist of Engine NG143, a double-engined locomotive with a single tender in its middle. It was originally built to journey on a narrow-gauge railway in South Africa but was rescued and restored by the volunteers who keep the Festiniog line and others across Wales, Scotland and England up and running.

“These railways really are a reminder of how British engineering and steam technology opened up the world and powered the Industrial Revolution. They helped us open up India, Africa, Asia. They are like the computers of today. Only these are coal-powered and a lot more fun.”

Across Wales, there are 11 such steam powered small railways functioning, drawing more than a million tourists each year to the principality.

Nora Williams is a teaching assistant for children with autism and lives in Liverpool but is spending her week’s half-term break riding the rails of the trains in North Wales.

She sits at the rear of the eight little cream and brown carriages that make up this lunchtime train that will soon be puffing and huffing up through the hills from Porthmadog to Blaenau Festiniog some 40 kilometres away – a journey that will take 90 minutes. No one said these old steam trains were quick.

“When you sit here you can video the full train ahead as it takes a curve,” she says. “You can’t beat the smell of the steam and coal. There’s something very magical about it.”

She grew up around trains. Her father worked for British Rail, the former national train company that was broken up and privatised between 1994 and 1997.

“Thankfully, these old railway lines are still operating,” she says, listing off those she’s travelled on and where she’s heading next. “I think that I would like to volunteer to help keep them running. It’s a real community and there must be tremendous satisfaction in knowing that you’re keeping part of history alive for future generations.”

Like most other little trains across rails, the Festiniog line began life as a means of getting Welsh slate from quarries and coal mines to ports where it could be shipped around the world to house and power the machines of the British Empire.

Today, the dour and grey village of Blaenau Festiniog is surrounded by towering slag heaps, the cast offs from where millions of tons of Welsh slate was extracted from the mountains, split by craftsmen into thin slices, then shipped around the world.

The material was cheap to produce, easy to work and was waterproof, used mainly as roofing tiles for the cities and towns that sprang up as housing for factory workers as the Industrial Revolution took root. The slate industry reached its heyday by the 1920s, with other cheaper materials then replacing it, putting thousands out of work – and spelling the closure of scores of similar narrow-gauge lines.

Back in the heyday, trains on the Festiniog line ran downhill back to Porthmadog on gravity, with often 90 or more little slate-laded wagons using just the power of gravity and the skilled techniques of three brakemen to stop them.

Now, it’s a more sedate affair, with all of the carriages following the strict protocols of today’s railway operating codes.

After 20 minutes climbing, the crew stops at Minffordd station – nothing moves for a good 15 minutes. An elderly train guard comes happily through the carriages, checking tickets. “Oh, we’re having signalling problems today,” he says cheerily. That’s little surprise – the Festiniog was the first in the UK to have a telegraphic signalling system – state-of-the art technology when it was installed back in 1912.

Soon again, it’s under way, stopping once more at Tan y Bwlch station where the two crew on the steam tender clamber up and fill its two side saddle tanks with hundreds more gallons of water for the second-half of the steep climb up to the terminal at Blaenau Festiniog. These are trains where time is a commodity to be enjoyed, moving to their own rhythmic sense of time and place.

The little trains of Wales

Bala Lake: A 15km return journey along Bala Lake in Snowdonia National Park.

Brecon Beacon: An 18km return journey through the superb scenery from Pant to Merthyr Tydfil

Fairbourne: A short train that more that 100 years old near the town of Barmouth and the coastal Mawddach Estuary.

Festiniog: A 40km line that runs from Porthmadog to the former slate-quarry village of Blaenau Festiniog.

Welsh Highland: Connecting the town of Caernafon with Porthmadog and running through the heart of Snowdonia.

Snowdon Mountain: A spectacular steam-powered train that climbs to the peak of the highest mountain in Wales.

Llanberis Lake: An 8km line that travels along the shores of LLlyn Padarn Lake.

Talyllyn: The world’s first preserved steam rail line covers 12km of spectacular scenery along the Fathew Valley.

Vale of Rheidol: Opened in 1902, the line climbs more than 200 metres over its 16km length.

Welshpool and Llanfair: This steep-gradient narrow-gauge railway features tight curves over its 25km route.