In one of his rare foreign policy interviews before being elected, Donald Trump told the New York Times in July 2016 that he is a “fan of Kurds”. The candidate also said that if elected, “very early on” he would work to fix relations between Turks and Kurds.

The paper asked him how. “Meetings,” he said. “So if we could put them together, that would be something that would be possible to do, in my opinion.”

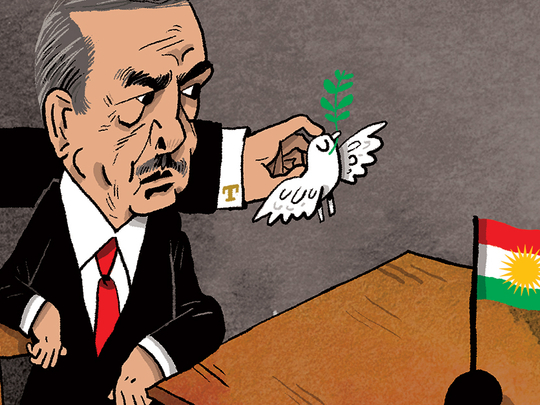

That may not be much of a plan, but it’s the last time any American politician spoke about securing a Turkish-Kurdish peace. Two years after the collapse of Turkey’s peace talks with Kurds, instead of “meetings,” what we have is a sprawling Turkish-Kurdish war across Turkey, Syria and Iraq, pitting a Nato ally against Washington’s main partners in the fight against Daesh [the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant].

Turkey considers the Syrian Kurds to be terrorists who are affiliated with its own Kurdish insurgents and has embarked upon a military incursion in the Syrian Kurdish town of Afrin. US policymakers are scrambling to avoid the spread of the conflict or worse — a direct confrontation between the Turkish army and the US special forces who work with Kurds further to the east. They go about it the usual way: urging restraint, promising Kurds continued cooperation, pledging to address Turkey’s security concerns and so on. The clumsy balancing act has been the hallmark of US policy in the north of Syria since the beginning of military cooperation with Kurds in 2015.

What Washington is not doing is working on a comprehensive political settlement to the Kurdish issue — with a peace plan between Turkey and Kurds as its centrepiece. This is based on the wrong assumption that there exists a Chinese wall between Turkey’s own Kurdish issue and the one in Syria, and that it is possible to juggle Turkey’s concerns with Kurdish aspirations simply by smooth-talking both sides. In reality, the Kurdish conflict has been there since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War and has now come to a boiling point. The conflict runs across Syria and Turkey with the same actors on both sides (yes, the Syrian Kurds are ideologically and politically affiliated with Turkey’s own insurgents, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party — or PKK) and, if unaddressed, will ruin any US efforts to stabilise northern Syria.

The Kurdish conflict is also at the heart of the strain on Turkish democracy. Much of the government pressure on Turkey’s academics, journalists and civil society has to do with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erogan’s recent reincarnation as a Turkish nationalist with an iron fist pursuing hardline policies on Kurds. Under both the Obama and Trump administrations, US governments hoped that turning a blind eye to Turkey’s democratic decline and heavy-handed treatment of its Kurds would give Pentagon a free hand to work with Syrian Kurds.

That was wrong. The real price tag on arming Syrian Kurds ended up being the destruction of Turkey’s democracy. What a raw deal to attempt to stabilise a war-torn region at the cost of destabilising a Nato partner!

Normalisation with Kurds

But, people often ask me, isn’t it a little Pollyanna-ish to ask mercurial Erdogan to return to democracy — and hence the peace process with Turkey’s Kurds? Not really. Erdogan is a pragmatist who at the moment has a dire need to consolidate his dwindling support base before next year’s presidential elections. After that, he could be amenable to a new round of talks — the “meetings” Trump talked about. Also, for a good part of the past decade, Erdogan’s government saw Kurds in its neighbourhood as an asset to expand regional influence — instead of a liability for its territorial integrity. Turkey was engaged in talks with the PKK and hosted Syrian Kurdish leaders in Ankara on many occasions. That only ended in mid-2015.

Kurds make up almost a fifth of Turkey’s population, and almost everyone here understands that at the end of the day, to secure Turkey’s long-term territorial integrity there has to be some type of normalisation with Kurds — rather than fighting them across Iraq, Syria and Turkey forever. Ankara’s current game plan seems to be shrinking the territory for Syrian Kurds before a final political solution there. Here is what to do. Washington must also urge Turkish forces to avoid civilian casualties and not to enter the densely populated city centre of Afrin — to prevent urban fighting that could inflame communal tensions between Turks and Kurds inside Turkey.

It is equally important to push the PKK to declare a ceasefire inside Turkey. That would ease off of the repressive rationale for continuing with a state of emergency — or embarking on cross-border operations.

Since Trump has a good personal rapport with Erdogan, he can then use his famous deal-making powers to urge his Turkish counterpart to return to peace talks with Kurds after the 2019 elections. To do so, Turks will almost certainly need assurances that Syrian Kurds will not seek independence or continue to run non-Kurdish towns such as Raqqa or Manbij. That can be addressed by providing inclusive local representation and a certain level of decentralisation in Syria’s north. Coupled with that, Ankara must start a peace process at home, with its own Kurds and their representatives.

The alternative to all of this is prolonged and transnational struggle between Turks and Kurds — further pushing Turkey into the abyss of a retro national-security state and Syria into a new level of destruction.

And who wants that?

— Washington Post

Asli Aydintasbas is a columnist and senior fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.