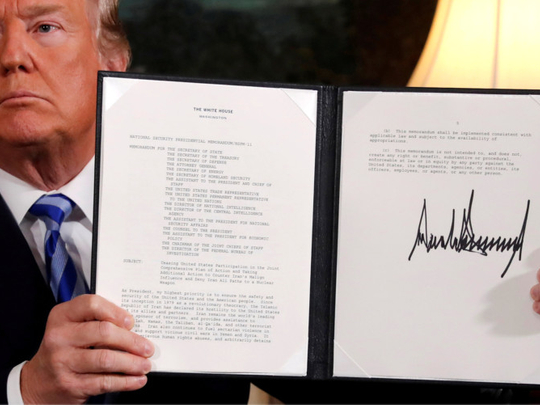

United States President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the nuclear deal signed with Iran and the European powers in 2015 doesn’t just make it likelier that Iran, too, will abandon the treaty and renew its push to make a bomb. It could also determine if the social unrest sweeping the Islamic republic deepens and further destabilises the regime. The government is facing perhaps its greatest opposition nationwide since the 1979 Islamic revolution. Trump’s decision will change how that story plays out in ways that will further destabilise the regime while giving conservatives more power for now.

The US decision is sure to exacerbate Iran’s economic crisis, promoting more political unrest. Although the Iranian regime will blame the US for an even greater decline of its economy if Washington reimposes sanctions, much of Iranian society no longer believes the claims of the regime. There is no doubt the Iranian economy is faltering. According to the BBC, in real terms, Iranians have become 15 per cent poorer during the past decade. While unemployment stands at an estimated 15 to 20 per cent in urban centres such as Tehran, it is 60 per cent in some rural areas. Unemployment for young people, who make up half of Iran’s population, is at 40 per cent, the New York Times reported.

The value of the Iranian currency, the rial, has plummeted from 36,000 to the US dollar (Dh3.67), when President Hassan Rouhani took power in 2013, to 67,800 to the dollar today. According to Iranian sources, Iran’s Central Bank has restricted Iranians from withdrawing dollars from their private bank accounts because there is a shortage of foreign currency, forcing Iran to funnel US dollars into the country from Iraq, where they are bought at reduced prices at auction. In 2017, the Iraqi Central Bank sold 15.7 billion in US dollars, and previous media reports, such as one by Reuters, have indicated that much of the money sold at auction winds up in Iran and Syria.

Trump says the plan is to reimpose sanctions, and when that happens, Iran will have more difficulty selling its oil on the world market, particularly in Europe, where firms are afraid of being penalised by US sanctions. Even if sanctions are not imposed now (the process is complicated), foreign investors will be less likely to take a risk by spending money in a country living under imminent threat of US sanctions.

Iran sells approximately 2.62 million barrels of crude oil per day. Approximately 38 per cent of these sales are to European companies, with the majority of sales going to patrons in Asia, according to the Financial Tribune, an Iranian economic publication. As foreign investors steer away from new investments in Iran, the country may be able to make up some of its lost sales by selling to China and India. (Before the nuclear deal was signed, it shipped just under one million barrels per day to Asia.) But Iran would be forced to do so at a discount. A reduction of oil sales, and thus a decline in foreign currency reserves, will make it difficult for Iran to meet its balance of payment obligations.

The European Union has suggested that it could put in place regulations to protect its firms doing business in Iran amid a new US sanctions regime. France and Germany, also signatories to the deal, indicated this week that they would remain in the deal regardless of the US decision.

But even if they stay in, there is a significant debate in the international business sector over whether companies should continue to buy oil from Iran if there are US sanctions. The so-called extraterritoriality of US sanctions applies to firms carrying out transactions in US dollars, even if these transactions are with non-US firms or branches. These sanctions allowed US authorities to fine French lender BNP Paribas nearly $9 billion in 2014. (The companies can carry out transactions in euros, but they have US subsidiaries that would be blocked.)

With new US sanctions, banks that did business with the Islamic republic or its trading partners around the world would be at risk of losing their accounts in the US. As Richard Goldberg, former lead Republican negotiator for several rounds of congressionally enacted sanctions against Iran, wrote in February: “Blocking regulations [by the EU] might shield a company from American-levied fines, but they cannot shield a British bank from losing its access to the US financial system. This time around, the downside of US sanctions would far outweigh the upside of Iranian trade.”

A further squeeze on the Iranian economy could have an unpredictable consequence, but more social unrest is almost guaranteed. In recent demonstrations, Iranians have blamed the regime for military spending that, they say, causes ordinary citizens economic hardship. This was never a major protest issue in the past. The opposition opposes the billions of dollars directed to Iranian military adventures and Iran’s proxies in the Middle East, such as Hezbollah and Shiite militias in Iraq. Analysts believe a large part of Iran’s $350 billion budget is spent on military and political interventions in Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Lebanon. A budget presumed to be leaked, according to Iranian sources, by President Hassan Rouhani this year put the figure at $10 billion projected for 2018. Iran’s leaders have overseen a 128 per cent increase in military spending over the past four years.

While the demonstrations began as complaints about the economy, they quickly turned to general opposition to the regime. Given the prospect of more sanctions, economic and political issues have become interlinked and are likely to inspire more protests. For example, women have been demonstrating for several months over the law requiring mandatory veiling. Even conservative women have joined other, more liberal women in the protests, which are ongoing. Rouhani has lost considerable power within the government and is weak with the political base that once supported him. The hardliners, too, have lost credibility, because of their corruption, their failure to deliver on economic promises and their military spending across the Middle East. The future could bring further polarisation in society — something the authorities in Tehran fear deeply — and could realign political power temporarily in favour of the hardliners.

— Washington Post

Geneive Abdo, a resident scholar at the Arabia Foundation in Washington, is the author of The New Sectarianism: The Arab Uprisings and the Rebirth of the Shi’a-Sunni Divide.