Most gardeners, amateur and professional, pretty much follow a set pattern when growing plants. They sow seeds and when the plant germinates, choose the stronger and healthier ones discarding the weak ones.

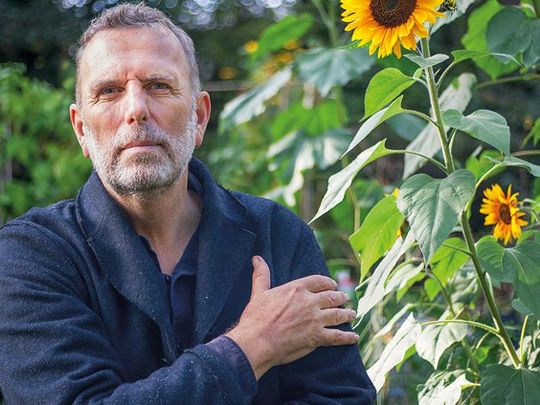

Allan Jenkins is unlike them.

Award-winning author, journalist and passionate gardener, he thinks differently. ‘I know the strong plants will be completely fine on their own,’ he says. ‘So, what I do is take the weak plant and find a really good space for them to grow.

‘That’s the plant that gets the most shelter, the most attention, the most light. I think the more attention, love and care something gets, the stronger it can become. [If nothing], at least I would have given it my best efforts for it to be strong,’ says the 63-year-old author.

In an exclusive telephone interview with Friday, the soft-spoken Observer Food monthly editor, whose latest book, Morning, has just been published, says that it is not just in the case of plants but ‘I try to give everything a chance and attention’.

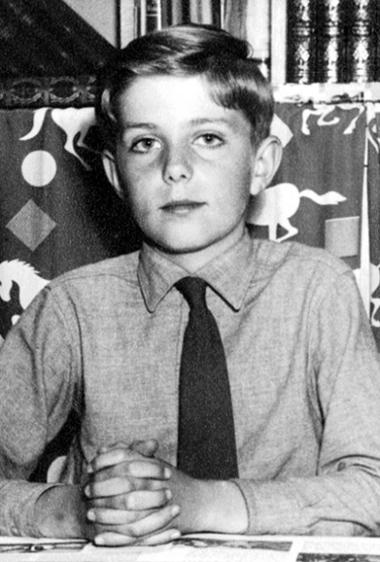

It perhaps stems from the fact that Allan himself was extremely lucky to get a second chance, perhaps several chances, in life. Raised in children’s homes and foster care in London, he and his brother Christopher were lucky to experience a new life when they were adopted by an elderly couple Lillian and Dudley Drabble. Christopher was six while Allan was five. In his first book, a memoir titled Plot 29, Allan recollects his early life illustrating it with vignettes about gardening – effortlessly grafting his passion for plants to his love for words. (The title of the book takes from the shared London allotment where he has been growing a variety of flowers and vegetables.)

A sense of hurt, loss and pain from spending early childhood in a care home frequently punctuates his work and his words. ‘Residential care was like a dogs’ homes,’ he says, ‘a place where abandoned pets are kept penned until someone might come along and take them.’

Fortunately for Allan, he could find comfort in the most trying situations. ‘I was just two months old and taken from everything - my mother, everything. Most orphanages in England during those years were not places where it would be easy to find contentment, yet I found it because I had a natural innate ability to find comfort. I was lucky; I had always a sense of safety that comes from my own self.’ He credits this facet of his personality to luck. ‘I don’t know what gave me that strength. The only thing I can say is luck.’ However, his brother Christopher did not share the same streak – an issue that continues to haunt Allan years after his brother’s death of lung cancer in 2011. Estranged for most of their adult years until an emotional reunion seven years ago, Allan says that the time spent in care home ‘left Christopher more damaged than me. He had a nervous tic and was very asocial. He had been harmed.’

Allan often wishes that he could have helped his brother in some way – provided him with more care, helped him grow better, done something more...

That emotion perhaps drives Allan to grow everything from seed. ‘It’s because of [the seeds’] helplessness,’ he says. ‘And the fact that they need caring. I think the garden gives me the ability to care for something. Like my brother wasn’t cared for. And perhaps I wasn’t cared for.’

The father-of-two believes that ‘It’s wonderful to be able to care for things, to give yourself in some way. It’s the ability to be able to use your privilege [to help] as best as you can.’

Having spent the early years of his life in residential care, Allan says that if there was one lesson he picked up it’s the importance to hone the skill of being lovable ‘so one could escape from there. ‘I do believe lovability is almost a skill,’ he says. ‘If you wanted to escape a children’s home – and if you were there you would want to because you would want to be part of a family – one way to do that is to hone the skill to be more lovable.’

Family is clearly a very important part of his life and not having had an opportunity to build strong familial bonds or be part of a loving one during his very young days continues to rankle him. ‘The need to be part of a family is such an iconic idea; to have a father, a mother… because you are very aware you are not like normal children. You are also aware you are quite like quarantined from other children.’

So disturbing and emotionally crushing was life in the care home that Allan doesn’t hesitate to liken it to ‘a dogs’ home’ to drive home the point of the importance of being lovable.

‘If you have decided to buy a rescue dog, then you go to a rescue dog home and you can’t but help noticing the happy dog; you are most likely to give a home to the dog – a happy dog – that runs up to you and appreciates you and gives you attention. It’s because we need rewards for our good actions. It’s a basic human thing,’ says Allan.

‘At the same time, if the dog moved to the back as you put your hand towards it or flinched, I promise you, it is unlikely to be the dog that you would want to take home.’

He sums it up in a line: ‘What it means is that lovable people are easier to love.’

While Allan honed his skills of being lovable, his brother Christopher could not because ‘he had been harmed. And people who have been harmed are less easy to love because they are nervous of it,’ says the journalist.

Apart from the need to love and be loved, a major quality that helped Allan come to terms with his past, is his optimism and gratitude not to mention enjoying the small pleasures of life.

Allan was five when his foster father gave his brother and him a packet of seeds each. ‘I grew these flowers and I couldn’t believe how miraculous it was. The winter brown ground became full of life and beauty, and I thought how wonderful that was; it was addictive in a way. It still is. We were told that you can plant three beans and they will become a hundred beans – which was amazing. So I was always attracted to planting.’

Allan, who clearly was born with green fingers, loved sowing and tending to the garden, lavishing his plants with love and tender care while watching them grow into sturdy plants. Aside from tending flowering plants, he also enjoyed raising vegetables.

‘Before a meal, my father and I would go out into the garden and we would pick some beans or peas or potatoes for the meal. Specifically for that meal. You would take what you needed. If you were having a Sunday meal and needed peas and potatoes, you would lift just enough potatoes and pick just enough peas for that dinner.

‘There was also the idea of freshness - something that is fresh from the ground or from the bush when it’s still full of life.’

The freshness, he insists, is something very difficult to duplicate. ‘I grow peas because to stand in a plot of land that was three months before just soil and is now green, and to eat what you have grown is so nice. I also believe that it’s important to give; it’s almost better than eating it yourself. It’s a lovely thing. Generosity is not celebrated very much.’

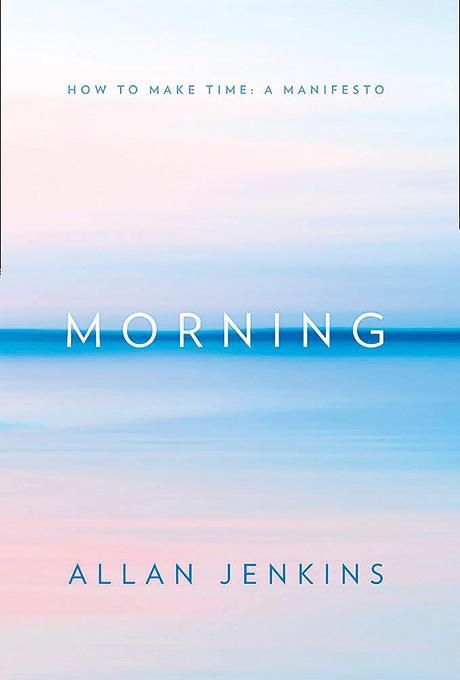

Another thing that is not celebrated much is the importance of making the most of mornings, a time of day that is extremely special to Allan. If you are a late riser, then getting up earlier once a week or even once a month can be life-changing, he believes.

‘Waking up early can free you to be more imaginative to maybe read, write, go for a walk…’ he says. Dawn and mornings should be celebrated – it definitely is the best time of the day, he exhorts, in his new book, Morning. To buttress his argument, he talks to a bunch of early risers from poets and painters to writers and chefs.

Also included is a neuroscientist who analyses sleep, a philosopher who discusses dawn, a fisherman reflecting on morning light…

Making the most of the early morning hours, Allan says, can throw open the doors to an amazing secret world, adding his book is a manifesto for dawn. He explores the Arctic Circle during the summer solstice to find out if dawn can exist when the sun never sets. Along the way, he chats with philosophers and priests, scientists and seafarers. Waking up when everything in nature is also waking up can be one of the most breathtakingly beautiful and mind-expanding things you could do, he says, making a case for larks.

An early riser, Allan says: ‘I write only in the mornings before its light.’ Up at 5am, Allan’s routine includes preparing a cup of tea – Early Grey from a single estate, sans milk – first thing in the morning. ‘Whether it’s dark or light, I never switch on the light. I know the room too well,’ he says. While the tea is brewing, he turns on the computer and starts writing. ‘If I’m writing an article or an interview, I plan beforehand the structure – how it starts and ends. It’s all very considered.’

The process is different if it’s a book that he’s writing. ‘In this case, I just watch and listen and then write.’

The book about his childhood took 15 months to finish. ‘Only twice in 15 months did I make a note of what I wanted to include in the book.’

Allan likens writing to fishing: ‘You cast out and then you wait and see if the fish bites and if it bites then you write it until it is finished. I give myself a couple of hours and it’s always quiet time; no one else is there. I can listen to myself as there are no distractions. I’m fresh, refreshed, alert, the world is awakening.’ Allan prefers sitting by a window facing East ‘so I’m aware of the dawn coming’.

He then runs a bath for his wife and prepares breakfast. ‘I think it’s a nice thing to do – run the bath and make the breakfast. ‘For men, it’s pretty easy – put on a shirt, a jacket and trousers and you are ready. But for wives it’s much more complicated. They have their hair to do, then decide on what they have to wear. So I take care of the other decisions that she doesn’t need to worry like the bath and breakfast.’

Breakfast over, he heads off to work. ‘I arrive slightly early while there is not many people in office. I then have time to think of how I want the day to go and how I want the magazine to develop. It’s easier to do the thinking and the planning when no one is around and fewer phone calls to answer.’ Once back home, he enjoys cooking – if he is not reviewing a restaurant. ‘Cooking is a great way to relieve stress. It’s very relaxing.’

Allan doesn’t use recipes relying instead on his instincts to prepare a dish – pan-fried halibut it is today. ‘That tastes good and is not complicated. I’m good at making fresh taste like it is supposed to.’

Despite a painful childhood, Allan prefers looking to the brighter side of life. ‘I don’t hold grudges, I don’t wish harm, I always believe in my own judgements. I have a wonderful family, an incredible wife. And am lucky enough to work for a kind of newspaper that reflects my views of the world,’ he says, the calm and stable positivity resonating in his voice. ‘I think what your parents can give you is the idea of how special you are. I think I always had an idea that I would be ok.’

Allan is convinced that his positivity is what carries him through life. ‘I always believe that things will be fine; that I can make them fine. I’m a great believer in making the best of things and actively working on things. I believe in generosity. I believe in kindness. In tenderness. I believe in recognising other people’s worth, of giving them attention. It works for me and it’s what I believe in.’

Also read: Writing, hiking and liberation with Cheryl Strayed

Also read: Being alive is extraordinary and should be celebrated, says author Caspar Henderson

He doesn’t forget to credit luck to working in a national newspaper. ‘I was born ridiculously lucky and have been working in national newspapers for some time. I can promise you - very few of my colleagues have been in children’s homes.

‘People who have been in the care system are highly represented in prisons and in addiction centres. Lack of safety is an extraordinarily powerful debilitating disease. You see that of people walking out of Syria. What’s important to them is safety.’

He admits that there were times when he wasn’t ok, ‘but I didn’t believe it would crush me’.

‘Truthfully, you are most likely to die early if you have not been looked after so well as a child. Poverty is also a disease as it is an economical state.’

Allan Jenkins’ book Morning is available in major bookstores in the UAE and on Amazon