BANEJ, India: Deep inside a protected Indian forest, a Hindu monk cast his ballot on Tuesday, ensuring a 100 per cent turnout at the polling station where he is the sole registered voter.

India is in the midst of the largest democratic exercise in human history and the country pledges to reach every voter, no matter where they live.

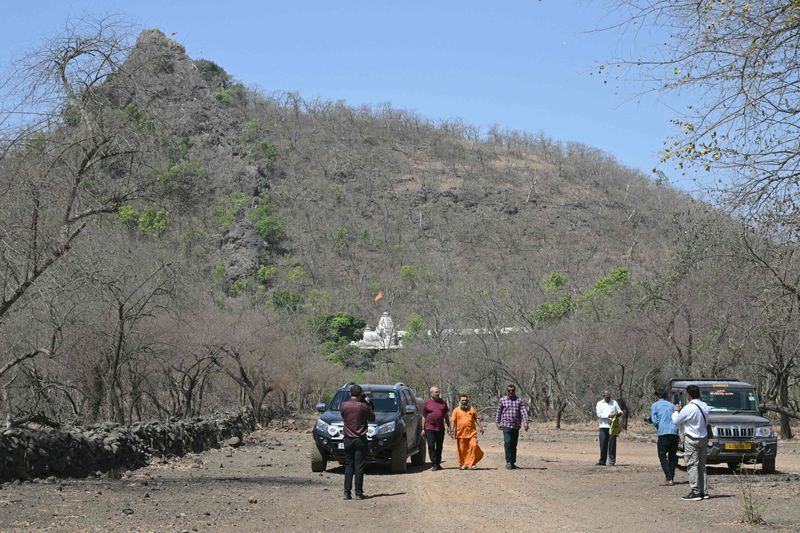

That has required polling officials to traverse through the Gir forest — the last remaining natural habitat of the endangered Asiatic lion — to set up a voting booth in Banej, where Mahant Haridas Udaseen is the sole resident.

“The fact that a team of 10 people came here in the jungle for just one voter shows how important each vote is,” the 42-year-old told AFP, holding up a finger marked with indelible ink to show he had voted.

Also read

More than 968 million people are eligible to vote this year, and electoral laws demand that each voter is no more than two kilometres (1.2 miles) away from a polling booth.

For polling officers in Gujarat, that meant a two-day trip including a long and bumpy journey by bus on unpaved forest roads to ensure the priest could participate.

Udaseen, clad in a saffron robe and his face smeared with sandalwood, arrived at the booth before lunch but election commission rules mean the booth must stay operational until the evening, even without another human for miles around.

The law also requires each polling booth to be helmed by at least six polling staff and two police officers.

“In a democracy, every single person is important,” said Padhiyar Sursinh, the presiding officer in Una, a town 65 kilometres (40 miles) away from Banej.

“It is our duty to ensure no one is denied his right to vote even if it means undertaking an arduous journey like this,” he told AFP.

After nearly three hours of travel in sweltering temperatures touching 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit), the team made its way to a remote forest department office where a polling booth was set up.

Sursinh and his team stayed overnight in the sparse building, sleeping on floors and having a simple meal of bread and lentils.

“We had to set up everything a day in advance so that the booth could be opened early morning at 07:00 am according to the electoral rules,” said Sursinh.

“There’s no cellphone network, so there is no room for errors here.”

Crocodiles and lions

India’s election commission goes to great lengths every five years to make sure not a single eligible voter is left out.

Braving freezing cold, a team will travel to Tashigang in the northern state of Himachal Pradesh to set up the world’s highest polling station at 15,256 feet (4,650 metres) above sea level when the constituency votes on June 1.

Udaseen is the custodian of a temple dedicated to the Hindu deity Shiva, sitting deep in the Gir forest next to a stream infested with crocodiles, moving there in 2019 after the death of his predecessor.

More than half a million people visit the forest each year, riding in open-top jeeps as they try to spot prowling leopards, jackals and hyenas.

But the main attraction is the Asiatic lion, of which there are only around 700.

Udaseen said he loved the sights and sounds of the forest and was grateful for the fuss being made over his electoral rights.

“I am loving the attention that I am getting as a lone voter in the forest,” he said.

“It shows the power of democracy and makes me feel like the most important person in the world.”