Manila: Traffic in Metro Manila recently earned top rank as the “worst in the world for a Metro area”. Decongesting the bustling capital has become an impossible dream. It's the single-biggest challenge for any Philippine leader.

Why is the traffic so bad in the Philippines? It’s the wrong question. Why is Manila traffic so bad? Now, we're talking.

The Philippines is a huge place. Luzon island alone, with a land area of about 110,000 km2, is similar in size to The Netherlands, Belgium and Switzerland put together. And there’s no, or next-to-none, traffic in most towns and cities outside the capital.

Most are getting hallowed out of people.

Where do they go? In cramped Manila.

The Philippine capital had an average travel time of 25 minutes and 30 seconds per 10 kilometers in 2023, compared to 24 minutes and 50 seconds in 2022. It has a congestion level of 52 per cent.

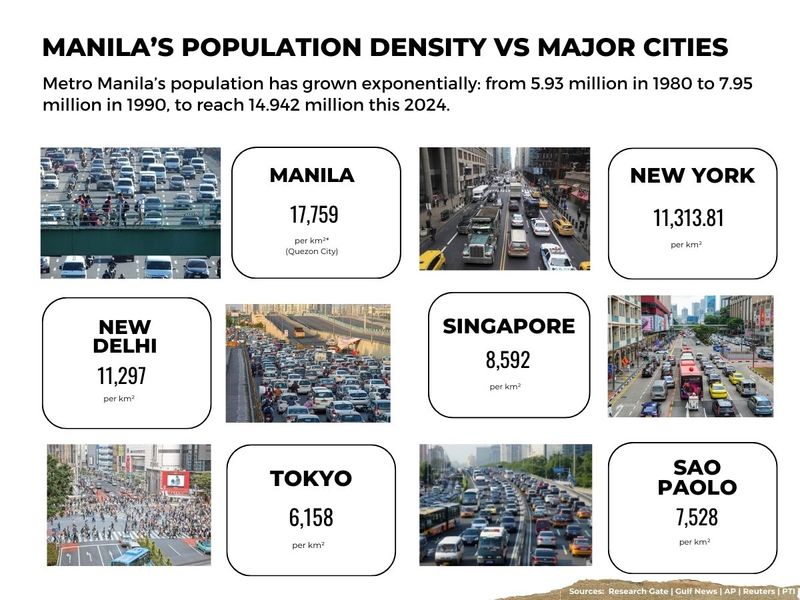

It's a complex problem. For one, the Philippine capital has more people per square kilometre (km2) than New Delhi, the capital of India, the world's most populous nation. It's one of the few megacities without a subway system (the under-construction Manila subway project won't roll until 2029).

The high demand for private vehicles, coupled with inefficient public transportation, underinvestment in infrastructure and continued outward expansion contribute to the situation.

Manila's being a congestion magnet is a sign of a deeper malaise.

On Wednesday (April 10, 2024), President Ferdinand R Marcos Jr. convened a “Bagong Pilipinas” Town Hall Meeting, focussing specifically on traffic concerns – where problems and solutions were discussed.

During the meeting held in San Juan City, the Philippine Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) unveiled several big-ticket projects to decongest traffic in the capital.

Observers readily point to “overpopulation” and overconcentration of jobs in the capital. While true, these must be viewed against the bigger context.

There are more fundamental reasons which are tougher to solve: under-investment in infrastructure, corruption, and a lingering lack of independent economic policy-making outside this economic and political hub.

More importantly, specific provisions in the 1987 Constitution keep the lack of economic freedom in the 17 regions outside Manila – that way. Outside the capital, no major economic decisions (specifically on investments and taxation) can be made.

It's an age-old conundrum. This republican-unitarian orthodoxy, anchored on "trickle-down" economics (vs. a partliamentary-federal setup), was etched in stone by the ultra-nationalist Charter writers back in 1986.

Let’s look at the challenges, and potential solutions:

#1. “Overpopulation”

The “overpopulation” tag applies only to Manila, home to more than 15 million inhabitants. One study even gave a much higher estimate – at 19 million.

Each day, Manila residents endure nightmarish congestion on roads and “highways”. The rest of the country is nearly empty.

To illustrate, visit a town or city just 100 km south or north of Manila. In Quezon province, for example, the population density is only 223/km2, versus Quezon City ("QC", one of the 16 component cities of Metro Manila), with 17,759 residents/km2, about 80 orders of magnitude higher.

That’s more than double the population density of tiny Singapore at 8,592/km2, whose land area is just one-fifth of the island of Masbate (with a population density of 556/km2).

Even worse, Manila has about three times the population density of either Tokyo (6,158 per km2) or Hong Kong (6,801 per km2).

If you think New Delhi (11,297 people per km2, the most in India), New York (11,313.81 per km2, the most in the US), or Shenzhen (7,000+ people per km2, the most in China ) are “overpopulated”, you ain’t seen nothing yet.

Ironically, the Philippine population growth, or “fertility rate”, actually shrunk to negative in 2022. There are deeper, institutional reasons why Manila is bustling at the seams – and a workable, long-term solution – which we’ll get to in a bit.

• In science and philosophy, it represents a foundational proposition not derived from any other.

• First-principles solution (FPS), or thinking, draws inspiration from this approach. It aids in analysing complex issues across engineering, business, or product domains by clarifying cause-and-effect relationships, facilitating innovative problem-solving, and promoting efficiency.

#2. Uneven development

Metro Manila’s population has grown exponentially: it has expanded from 5.93 million in 1980 to 7.95 million in 1990, 9.93 million in 2000 and is estimated to reach 14.942 million this 2024.

This took place while the country’s population growth rate – which stood at 2 per cent for much of the 20th century, is declining in most regions of the Philippines, according to the US National Institutes of Health data.

The most recent five-year survey of the Philippines’s headcount, in 2022, saw this "negative fertility rate", dropping below 2.1 live births per woman – the level at which a population naturally replenishes itself. So while the rest of the country is hollowing out of people, Manila continues to get cramped.

#3. Inefficient, insufficient public transport system

Manila’s public transport network has been a constant challenge. Big projects are on the way to help solve this, i.e. the Manila Subway, and more Metro lines. But these take time to build.

Manila has only 3 light rail lines currently working, with the extension of LRT 1 to Cavite bogged down for more than 20 years by right-of-way (ROW) snags and reports of corruption. According to Top Gear Philippines, the under-construction MRT-7 line is also facing ROW hitches, pushing back completion and full operations by another two or three years, with only 12 of the 14 stations set to be operational by end-2025.

ROW issues usually arise from court challenges lodged by owners of affected land who want the most compensation, while paying the least amount of taxes. Result: timelines of engineering solutions are dealt with primarily by lawyers.

By comparison, Sao Paolo (population density: 7528 per km2), already the most populous city in the southern hemisphere with 12.33 million people, has 12 rail lines: a five-line Metro system, a six-line suburban rail network and a monorail.

It’s no surprise that infrastructure in the Philippine metropolis is unable to keep up with vehicle sales, leading to daily scenes of traffic nightmare.

This, despite the 42-km “Skyway” built to cut traffic from Manila’s northern to southern corridors.

The inefficient public transportation has been decried by President Marcos himself, who has cited London and New York for the dominance of mass transport systems in those cities, used by both rich and poor.

In the Philippines, private vehicles – especially armoured cars of politicians – have a distinct swagger.

#4. Limits on economic policy-making outside Manila

The Philippines is a unitary republic. It has two legislative chambers, a 24-member Senate and 300+-member House of Representatives). Crafters of the 1987 Constitution were concerned that a federal set-up would “fragment” the country.

The result: all economic decision-making is concentrated in Manila. So are the economic opportunities.

Added to the inadequate planning and sub-urbanisation is the proliferation of informal settlements in city centres – mostly from the provinces looking for job opportunities in the capital.

Moreover, the establishment of central business districts along major thoroughfares has created a cornucopia of headscratchers.

Constitutional challenge

A key challenge springs from certain provisions of the 1987 Charter itself: it provides that the 24 Senators must be elected "at-large", i.e. under plurality voting. This means the entire country, with a 36,289-km coastline, the fourth-longest in the world, forms only one "district" in its senatorial elections.

This has led to an absurd situation: out of the 17 regions of the Philippines, most of the 24 Senators are from Manila – some of them are siblings, parent-and-child, or are popular entertainers/sports personalities and their offspring.

Each senator has a budget of several hundred million pesos, making the cost of legislation unjustly high for the great majority of Filipinos, with 40 per cent living on less than $2 per day, according to the ILO data.

The only sure and meaningful legislation passed by both chambers is the General Appropriations Act (the annual budget), which in 2024 has balooned to 5.6 trillion pesos (about $99 billion).

Skewed representation

Senators serve six-year terms with a maximum of two consecutive terms, with half of the senators elected in staggered elections every three years. This skewed representation has been the cause of self-inflicted harm, and frustration, among the Filipinos.

There’s been an on-and-off drive to amend the Charter, which has stood unchanged since 1987. Nothing’s come out of it. Current members of the Senate, understandably, are against any tweaks that would effectively scrap the chamber in its current form.

There’s been a growing call for a federal Philippine setup, where power is divided between the central government and local, or “state” governments.

Again, nothing.

Except for BARMM. The Philippines already has this sort of arrangement – the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) has its own ministers of health, education, public works, social services, planning and development authority and others.

BARMM’s economy has been growing at a faster clip than most parts of the country: 7.5 percent in 2021 and 6.6 per cent in 2022.

Fundamentally, the key to solving the Manila traffic mess, aside from the usual engineering solutions – more ramps, expressways, public transport – is the first-principles-driven development of the 17 other regions.

Here's why: While building more roads and skyways in the capital might seem like a solution, it can actually induce more demand. Meaning more cars will fill the new space, and more people who flock to the city, creating a net increase in traffic.

Solution: Whole-of-nation approach

Besides the engineering solutions, it requires a comprehensive action to address the underlying cause.

To start withstart: a change of vision.

How? By empowering the regions to handle their own economic laws, taxes/finances, development plans, health, education, infrastructure, and Customs, among others.

Let the regions compete with each other in good governance, infrastructure, human indicators.

By unleashing economic potential beyond the confines of Manila and implementing (or copying from other countries) simple engineering solutions – clearing obstacles, swiftly resolving ROW disputes, building new links, circling roads, and enhancing public transport – the suffocating congestion gripping Manila from all sides can be dramatically alleviated.

This is easier said than done. Yet, having the worst traffic in the world for a metropolitan area is just a sign of worse things to come. Do Filipinos and their leaders have the clue and resolve to do what it takes?

Only time will tell.

The grim alternative is this: if we keep on doing what we’ve always done, we’ll always get what we’ve always got... till Thy Kingdom come.