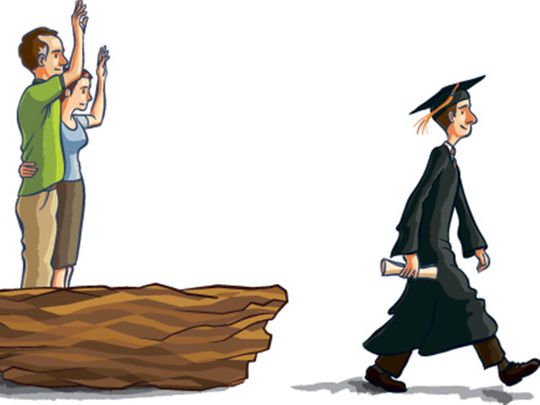

It was a 20-minute window of conversation that Simora Spazzini, an Italian expat based in Dubai, missed the most. “When it was getting dark but it wasn’t dinner time yet, I used to have the longest and best conversations with my daughter in those moments,” she explains. And so, to keep from spiralling down the staircase of misery those first two months after her second daughter had moved out, she kept a full calendar at all times.

“I was organising an event every night, like going to the cinema or grocery shopping at that time or meeting a friend or sports or walk or something. We had a very intense social life for a couple of months,” she explains. It was all to cope with empty nest syndrome. (Her elder daughter had left a couple of years earlier, she says, but the second send-off was worse.)

The term empty nest syndrome, which flares up around university admissions time each year, was first coined in 1914 by American author and activist Dorothy Canfield, and used to describe the feelings of gloom and doom that affected some women as their youngest left the nest. The syndrome got still more recognition in the 1970s and grew to include both genders’ behaviours and moods.

Fortunately for Spazzini, this was a grey cloud that moved on. She says as the months rushed on, she and her husband discovered a sort of time crawl; they had slipped into routines of decades gone by. “I realised that we had slowly adapted and we were happy, and we were moving back into a routine we had 20 years earlier, before we had kids. So we each had our days planned, we had our own things to do and our jobs. We found we could improvise and we were free to do things - and we didn’t have the mental responsibility of [providing for the kids during the day]. That translated into mental freedom. And we really are in a very good place and we have learnt to appreciate when we have the girls and we can also be quite content when it’s just the two of us in Dubai,” she laughs.

US-based Psych Central, an independent mental health information and news website, says empty nest syndrome has three phases:

Grief: “Empty nesters can feel a deep sadness and may even begin to experience the five stages of grief,” it says. These include denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

Emptiness: “You may feel adrift like a boat without a rudder,” it adds.

Fear and worry: “You might be uncertain and afraid of your life ahead. You may be preoccupied with your child’s well-being, too,” it says.

This uncertainty - caused by a metaphorical umbilical cord stretched taut - and the access of time one finds themselves with gives rise to new anxieties. Mandeep Jassal, Behavioural Therapist at Priory Wellbeing Centre, Dubai, explains: “Many parents naturally become attached and constantly focused on prioritising their child’s needs, interests and overall wellbeing, be it with school and academia, having fun and being creative together or rituals of connecting through shared mealtimes. When children leave home, it can cause a significant adjustment for many parents, often resulting in feelings of loss, frustration, depression and fear.”

For the children getting ready to explore a new home, perhaps a new country, the reel of adventure and homesickness compete. Swati Mulchandani, a 17-year-old Indian expat who will be flying out to the UK for university next year, explains that one of the hiccups of setting the new goal was to alleviate her parents concerns. “When I told my parents that I wanted to go abroad for university, they were slightly reluctant at first because they didn’t want to leave me all alone in an unknown place. They were worried about whether or not I would be able to deal with the pressure that comes with living alone but when I explained to them the reason behind my choice, they started coming to terms with it slowly,” she says.

However, she does add that her parents have grown a little overprotective since then. “At times, I definitely feel like they just want me to be with them all the time but I think that’s just their way of showing that they care. My parents are now my biggest cheerleaders, and they try to help me in whichever way possible.”

Seventeen-year-old Anooshka Chiddarwar, who is also eyeing a UK degree next year, recalls a similar response to her wanting to study abroad. “I wish I could tell them not to worry as I will always try my level best to make them proud both in terms of my personal and professional life, even when I go away from home,” she says.

Some parents like a hands-on approach to getting their kids settled in. “They [my parents] are very involved and they make sure that I’m writing my essays on time,” expat Anwesha Parida says. “I want to leave the nest and be more independent and my parents are quite supportive of me because they want me to have a successful future. They helped me with the whole admissions process. They’ve helped my elder brother, and so they are quite well informed.”

Who misses whom?

Once the novelty of a new situation wears down, that’s when the feelings of loneliness begin to settle in. “While you are in the process of [getting admission, planning things out], you don’t really come to know what it’ll be like once they leave the house,” says Dubai-based mum Jaishri Jaiswal. “The first three months were very difficult for me. Whether I was cooking anything or watching anything, I used to miss her. I didn’t cook anything that she liked for so many days. That was my way of coping.”

Her pet rabbit helped her heal, she recalls, by being a needy companion. “I would say at least six months a mother will take to understand that this is how things will be,” she says.

And the other thing that gave relief, she adds, was making plans and scheduling time for one another. “We were missing each other so we would call each other at night, when both were free and we would have a chat. We made a routine and we still follow that routine,” she laughs.

Coping mechanism

Behavioural therapist Jassal offers the following tips for empty nesters trying to cope:

1. Build a support network of family and friends: Talk to those going through a similar situation, as this will help you feel less isolated.

2. Develop hobbies and interests: Always wanted to learn salsa, but have been putting it off for the longest time? Now is the time to give it a try!

3. Be kind to yourself. There will be moments or days it doesn't feel the same, and that is okay. Notice the thoughts and feelings, allow and accept them, then gently continue bringing your attention back to the present moment with the activity you are doing, such as watching television or reading.

Write to us at parenting@gulfnews.com