Jessie Childs’s account of cloak-and-dagger intrigue in “Tudor England, God’s Traitors: Terror & Faith in Elizabethan England” (Bodley Head, £25/Dh144), conjures a John le Carré-like underworld of political double-dealing and “spiery” (as the Elizabethans called it). This was a time when moles were planted in Catholic seminaries and Elizabethan diplomacy created a looking-glass war in which priest was turned against priest, informant against informant. In crisp prose, Childs recreates a world of heroism and holiness in “Tudor England”.

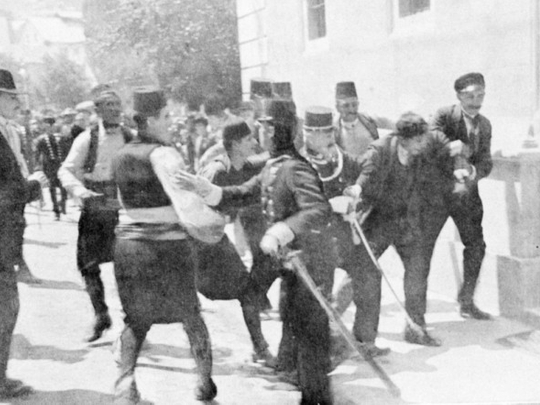

Tim Butcher’s study of the Bosnian Serb who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914, “The Trigger: Hunting the Assassin Who Brought the World to War” (Chatto & Windus, £18.99), is a triumph of punctilious scholarship and research. Gavrilo Princip set in motion an unintended chain of events that culminated in carnage such as the world had never seen. At 19, Princip was not of an age to be executed; instead, he died in captivity in Theresienstadt in 1918, having contracted tuberculosis. Butcher (the author of the bestselling Congo narrative “Blood River”) has written a marvellously absorbing book on the nature of one man’s political grievance and its terrible aftermath.

“Partisan Diary: A Woman’s Life in the Italian Resistance”, by Ada Gobetti (OUP, £22.99), was originally published in Italy in 1956 with a foreword by Italo Calvino. (The author displays an “ironic modesty” and “simplicity” in the writing, Calvino wrote approvingly.) The act of keeping an anti-fascist diary of this sort during the German occupation of Italy carried an automatic death penalty. Gobetti jotted down her entries in a cryptic English that only she could understand; at the war’s end, she deciphered the jottings for eventual publication. By a fluke, the Germans never suspected her Turin address — the now legendary 6 Via Fabro — as a Resistance nerve centre. Her diary, a key historical document, is thrilling and unforgettable.

Eric Hazan is not a professional historian, but he has the historian’s gift for trawling archives fruitfully. “A People’s History of the French Revolution” (Verso, £20) chronicles the 1789 upheaval in all its guillotine gore and popular fury. Hazen has chosen to write an “everyman’s story” that concentrates on the experience of ordinary housewives, journalists, printers and sans-culottes. The combination of bottom-up testimony with quick authorial intelligence lends the history a vivid immediacy.

Carrie Gibson, a former “Guardian” journalist, sees the West Indies as a “crossroads” for people, commerce, plants, animals, slaves and disease. “Empire’s Crossroads: A History of the Caribbean from Columbus to the Present Day” (Macmillan, £25) is an ambitious undertaking. Apart from the accident of their having been under British rule, Barbadians, St Lucians, Guyanese and Jamaicans have little in common with one another. Were you to superimpose a map of Europe on the Caribbean, Jamaica would be Edinburgh; Trinidad, north Africa; and Barbados, Italy: the islands are that far apart. With rare narrative verve and a gift for synthesis, Gibson compresses the islands’ histories into a wide-ranging, vivid narrative.

Hugh Trevor-Roper, the conservative Cambridge historian, served in British intelligence during the 1939-45 conflict and became expert on the subject of Soviet and Nazi espionage. His Cold War essays, collected in “The Secret World: Behind the Curtain of British Intelligence in World War II and the Cold War” (IB Tauris, £25), condemn the “squalid trio” of Cambridge agents — Maclean, Burgess and Philby — who betrayed compatriots to the Soviet Union. Trevor-Roper sees a priestly or hieratic aspect to their treachery as they sent unsuspecting novices to “our friends” in the Kremlin and a certain death. The essays, first published in the Spectator, Encounter and New York Review of Books, radiate a waspish elegance.

Richard Vinen, in “National Service: Conscription in Britain 1945-1963” (Allen Lane, £25), provides a fascinating history of British call-up and its personnel and personalities. The subject has been rather neglected by academics, but Vinen fills the gap brilliantly. The notion that conscription fulfilled a disciplinary purpose (the “short, sharp shock”) is a retrospective one, according to Vinen. The reality is that Britain needed reserve troops in the event of a nuclear conflict and to fight its various wars of decolonisation.

In “Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War” (Bodley Head, £25), Jerry White portrays the British capital as a teeming nerve centre of the allied war effort. Whether they liked it or not, Londoners of all backgrounds were implicated in the carnage of the trenches. Each day, blinded and disabled servicemen arrived by hospital train at Waterloo from Flanders and the Somme. With the mud still caked on their boots, they brought the battlefield into the heart of the metropolis. White deploys sources ranging from unpublished memoirs to diaries and interviews to write a first-rate social history.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd