SAN FRANCISCO

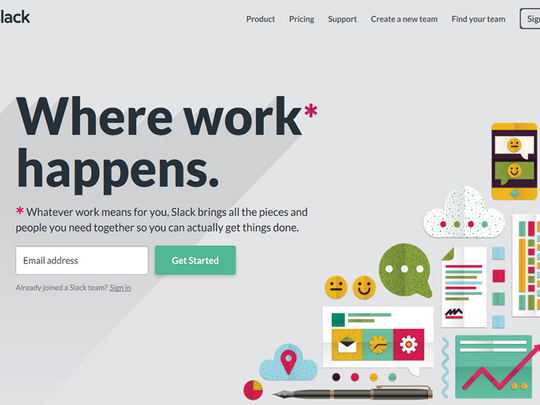

Slack is the classic Silicon Valley accidental success. Born three years ago, with roots in a failed video game, the messaging software is now used by five million people.

The company behind it, Slack Technologies, found success by combining something that Silicon Valley fetishises — rich data on how people use a product — with something it often overlooks: How do people actually feel while using it?

This combination produced an unlikely hit that, when it became available in 2014, grew mostly by word of mouth, which is unusual for corporate software. Last year, the privately held company was valued at nearly $4 billion.

Now Slack faces a significant new challenge. It has become big enough to draw a competitive response from giants like Microsoft, but not big enough to have the roster of large corporate clients that it needs to compete with the giants.

Last fall, Microsoft announced a direct Slack rival called Teams, to be given free to all 85 million users of its Office 365. At the same time, Facebook made its work collaboration tool, Workplace, widely available free. Atlassian, a smaller company, has signed big customers, too.

As a result, Slack, which built up momentum as a lovable underdog, must fend off some of technology’s largest and fiercest competitors if it wants to be more than a niche tool for small businesses and teams.

Microsoft already offers ways for employees to collaborate. And while its offerings have not been viral hits, they have offered boring but important features that big companies demand, like strong data security and regulatory compliance controls.

There is no illusion within Slack that success is certain. But Stewart Butterfield, the chief executive, said small tech companies with new ideas had long defeated larger rivals that tried to copy them. Think of Apple’s beating IBM in personal computing, Google’s beating Microsoft in search and Facebook’s crushing Google in social networks.

Slack is the product of Butterfield’s second failed attempt to make a video game. His first, Game Neverending, had a photo-sharing feature that became more popular than the game. It became Flickr, which was sold to Yahoo for $25 million in 2005.

In 2011, he introduced another game, Glitch, in which people cooperated to build a shared world. (Misbehaving players got a timeout.) At its height, the game was costing the company $500,000 a month and bringing in $30,000, so Butterfield shuttered it in late 2012. A few employees stayed on to build out the messaging platform that Glitch engineers had used to talk among themselves. That project became Slack.

Slack was officially introduced in February 2014 and today has 5 million daily users, up from 4 million in October. Most users are on a free version, but about 1.5 million pay Slack $6.50 to $12.50 a month for features like message storage and search. The 800-person company is on track to generate more than $200 million in revenue this year, but it is not profitable.

Initially popular with small teams of software engineers who wanted to work remotely without cumbersome videoconferences or email, Slack was not designed for big companies. Users chat in “channels,” typically organised around a few well-defined tasks.

“The overhead of working among different offices becomes less of an issue” with Slack, said Nick Coronges, chief technology officer at R/GA, a 1,000-person design and marketing agency with offices in several cities.

Collaboration software like Slack is not new. Google’s Wave, which started in 2009 and shut down in 2012, was supposed to replace email with a messaging tool, but conversations were too hard to follow and track. Atlassian, an Australian software company, released a team collaboration platform in 2004 and acquired Slack’s nearest start-up rival, HipChat, in 2012.

But Slack has focused on making a product that people love, a strategy that is more common among consumer companies like Apple, Snap and Spotify.

Unlike some Silicon Valley companies, Slack believes humans are as important as robots. All executives, including Butterfield, have fielded the 6,000 customer support calls and 2,800 Twitter messages that come in each week. The average turnaround time for a help request is under an hour.

“I get worried if I see customer satisfaction scores dip below 97 per cent,” said Ali Rayl, Slack’s head of customer experience.

If Slack can dovetail seamlessly with how people behave, feel like second nature to use and strongly appeal to employees, taking it away could become “like taking off your astronaut helmet in space,” Butterfield said.

— New York Times News Service