1. The unlikely openers

Though the years had advanced on both of them, neither Kiwi Dipak Patel nor England veteran Ian Botham were shock selections for their respective sides at the 1992 World Cup, but it was their specific tactical deployment that took the cricket world by surprise.

Botham was used a pinch-hitting opening batsman in a squad loaded with allrounders and Patel, to even his own surprise, was recast from journeyman batting all-rounder to off-spinning opening bowler.

Given the composition of the England squad - there was no specialist opening batsman picked to partner Graham Gooch - and his small measure of previous success in the role, it was perhaps less surprising that Botham should play the pinch-hitter role but even all these years on it remains a kind of oddity to watch 36-year-old Beefy opening up.

As is so often the case with novelty tactics, it wasn’t exactly a roaring success either. Botham’s 192 tournament runs came at 21.33 and included just a single half-century. Patel’s returns were modest, but the mere sight of a part-time off-spinner opening the bowling on the world stage took the cricket world by storm.

It’s hard now to even imagine how or why we found it so earth-shattering but we did and it was. It came as a slight shock to Patel too as it turned out; after an earlier suggestion during a team net session, New Zealand brains trust Martin Crowe and Warren Lees only informed Patel that he was taking the new ball at a team meeting the night before the tournament opener against Australia. Again, the figures are probably not as impressive as you’d think.

In New Zealand’s heart-warming charge to the semi-finals, Patel actually took just eight wickets in as many games but his economy rate of 3.10 was a tournament best and allowed Crowe to apply early scoreboard pressure on the unsuspecting Australians. Other opponents knew what was coming but still didn’t get him away.

To less impact still than Botham or Patel but spawning an enduring piece of trivia nonetheless, the 1996 tournament saw Warwickshire off-spinner Neil Smith partner first Alec Stewart and then his skipper Mike Atherton at the top of the England batting order. That was an unlikely turn of events given that Smith had slotted in at 9 and 10 respectively in his only two prior one-day international appearances.

His big moment came against the UAE. In sapping heat, Smith claimed three wickets during the UAE innings of 136 but, after racing to 27 from 31 balls at the top of the English order himself, a stricken Smith started vomiting violently and had to be assisted from the ground, retired ill. “He had a pizza last night,” explained the ever-quotable Ray Illingworth, “now it’s on the field out there.”

2. South African sacrifice

Jonty Rhodes is flying through the air like Superman to run out Inzamam-ul-Haq. For most of us it’s the first sighting of Allan Donald’s “White Lightning”. Then there’s Kepler Wessels - is he an enemy of the state or do we give him a cheer? Too dour for cheering, perhaps. Don’t forget the farcical sight of the SCG semi-final scoreboard against England. Before he’d even been granted the right to vote in his own country, South African all-rounder Omar Henry had represented his nation on the world stage, at that 1992 World Cup.

We always knew there’d be a political footprint to South Africa’s reintroduction to international sport, but they left plenty of cricketing impressions too. Understandable then that it takes a while to rake up memories of what happened beforehand, when the selection of that Proteas squad sent an entire nation into a state of turmoil. The decision to cut much-loved Clive Rice - incumbent national captain and holder of the kind of public approval rating that suggested he’d continue in the role - plus veteran batsmen Jimmy Cook and Peter Kirsten from the squad for cricket’s marquee event was scandalous.

It was worse than that, in fact. The veteran trio actually missed out entirely on a provisional list of 30 “probables” from whom the final squad would be chosen. But how to vent your spleen in such technologically austere times? Well, petitions of course. Lots of petitions. South Africans had waited 20 years for this moment and what, these selectors were just going to turf the stalwarts? “I was as staggered as the rest of the country,” South Africa’s coach Mike Proctor later told ESPNCricinfo .

3. The calculated gamble

You only have to look at the rapid turnover of national selection jobs to know that whilst being a national hobby in most cricket-loving nations, the art of choosing the perfectly balanced side is both taxing and difficult.

With multiple voices in the room, concessions and compromises are necessary and not a little bit of foresight. When and whom do you “pick and stick”? Has this guy got credits in the bank? Is this one ready yet? Is that one talented enough to warrant the hassle and justify the risk? Isn’t he too old?

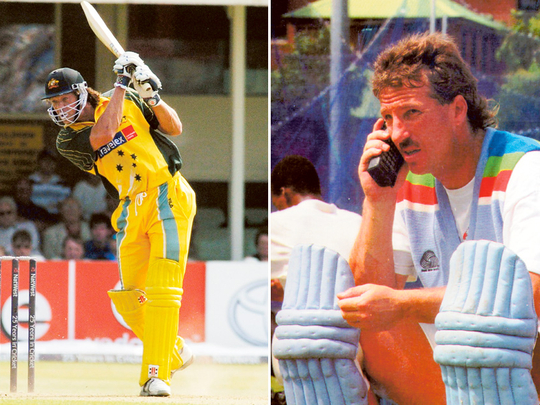

The selection panel for Australia’s 2003 World Cup squad had reason to ponder a few of these questions when it came to a decision on mercurial all-rounder Andrew Symonds. There were ample grounds on which to leave him out. Symonds’ 54 one day internationals to that point had left him with a rapidly-deflating batting average of 23.81 and the unbeaten 68 he’d scored in his third match - now four years into the rearview mirror - remained his best effort. His bowling? An acquired taste.

At the insistence of captain Ricky Ponting, Australia’s selectors cut Symonds some slack and picked him more or less on talent and potential alone. You couldn’t justify it any other way. On the tournament’s eve the defending champions were in a state of mild crisis too; Shane Warne sent home after a positive drugs test, Michael Bevan injured and Darren Lehmann suspended for racial abuse. Could a flake like Symonds turn it on when his team needed him most?

At 86-4 in the 16th over as Symonds strode to the crease in his side’s first pool game against Pakistan, the world was about to find out. Internal expectations were possibly a little higher than those held by the average fan but finally something clicked. Everything clicked, in fact. Watchful at first (his first 50 took 60 deliveries) Symonds launched an unforgettable attack on a rampant Wasim Akram, plus Waqar Younis and Shoaib Akhtar, raining 18 boundaries and a pair of sixes on his way to an unbeaten 143 from 125 deliveries. His second 50 came from just 32 balls. Symonds had arrived.

There was more to come too; 59 against Namibia, a match-winning 91 not out in the semi-final against Sri Lanka when no other man progressed pass the 30s and then a symbolic skittling of the tail in the Cup-winning triumph against India. By the time Australia had completed their three-peat at Bridgetown in 2007, Symonds’ blade drew a touch under 40 per redemptive innings.

“It was an example of a captain’s faith in a player,” explained Ian Chappell, “how important it is and how that faith can be rewarded, particularly if the captain has picked the right bloke.”

Not only was it the definitive Symonds but a catalyst too for everything else of value in his international career. With that you’d expect it lodged well in his mind’s eye. Well not quite. Symonds had to re-watch it on DVD before passing any judgment in his autobiography. Most of the rest of us remember it a little better.

4. Graeme who?

Even by the standards of the Packer era, when the establishment Test side’s changerooms boasted a revolving door of creaky veterans and greenhorn Sheffield Shield triers, Graeme Porter must remain one of the more obscure individuals to have donned a baggy green. Doubly so considering he never actually won a Test berth.

Porter wore the famous cap as perhaps the least recognised and recalled member of Australia’s 1979 World Cup squad which, despite having travelled to England weeks after the truce had been reached between Packer and the establishment, contained only players who’d rebuffed or been overlooked by the travelling circus of Packer’s World Series cricket. Not so the West Indies, who welcomed their stars back with glee.

Thus Kim Hughes, just 25 at the time, had come by the Australian leadership almost by default. In actual fact, the selection of a number of other captains was a major talking point pre-tournament in ‘79. India, on the mere suggestion that Sunil Gavaskar might have flirted with a Packer-funded excursion, replaced him with Srinivas Venkataraghavan. Pakistan’s Asif Iqbal had taken the job from Intikhab Alam just prior to the 1975 tournament and now he unseated Mushtaq Mohammad in the musical chairs arrangement.

Under Hughes, Australian Porter was joined by a host of other exotic selections; luxuriantly-moustached Victorian Jeff Moss, jobbing all-rounder Trevor Laughlin and ginger South Australian wicketkeeper Kevin Wright among them. This “B team” was rated only a 20-1 chance of taking out the tournament - potentially even a generous assessment - and for many it would be their last hurrah at international level.

Contrary to some accounts, Porter actually played his role to perfection. His debut came in an inglorious 89-run defeat to Pakistan at Trent Bridge - one that all but ensured Australia’s tournament exit at the group stages - though the miserly bowling all-rounder couldn’t have worn much blame on account of 1-20 from 12 overs of unerring line and length. There followed 2-13 off 6 as the Australians routed Cananda for 105 in a handsome but ultimately meaningless win.

Their World Cup was over and so was Graeme Porter’s blink-and-you’ll miss it career, witnessed in its dying moments by a dreary Edgbaston crowd of just 1,200. Not that anyone particularly noticed it at the time, but Porter had topped the tournament bowling averages. Quite a way to go out.

5. Pakistan’s calculated chaos

It’s hard to do justice to the head-scratching bafflement and unbridled joy of Pakistan cricket without resorting to cliche or at least mild condescension. As a cricket nation their story pinballs so frequently between the brilliant and the bizarre that sometimes the two qualities seem indistinguishable from one another. With Pakistan it’s mostly about the ride but in 1992 it was also about the destination.

We know them as Imran’s “Cornered Tigers” now, of course, but the selection process that led to Pakistan’s final tournament squad was perhaps appropriately bizarre and unconventional. Fourteen willing men were what tournament guidelines required but instead they sent a swollen advanced party of 17 in the hope of winnowing their number down to successful combination.

Much of the early selection debate focused on the availability of batting lynchpin Javed Miandad, then saddled with a serious back injury that had put his participation in doubt. Once declared fit, Miandad joined Imran as the only player to have turned out in all five tournaments since the first in 1975. No wonder he was feeling the pinch. Diagnosed with two stress fractures of the back just days before the tournament, bowling ace Waqar Younis flew home. In his place, pairing with the untamable talent of Wasim Akram, slotted the unlikely Aquib Javed. Imran battled on with a shoulder complaint.

Unlike any other visiting nation, Pakistan management went as far as organising two first-class fixtures (in Bendigo and Devonport, no less) among its six (yes, six) warm-up games in the Australia as players appeared from and disappeared to various airports at regular intervals. It seems so quaint now that the likes of Imran, Wasim and Rameez tuned up for their historic title against the likes of Paul Nobes, Darrin Ramshaw, Danny Buckingham and Bruce Cruse, but the elongated and unusual preparation can’t be said to have hurt their cause. Those warm-up games were hardly a pointer to global domination, mind. Losses came against Tasmania, South Africa and eventual strugglers Sri Lanka, with Pakistan beating only an uninspired ACT XI before the tournament proper kicked off.

Injured or else unrequired, would-be participants Shahid Saeed, Akram Raza and Saleem Jaffar were all sent packing and thus denied their place in history. Amusingly described as a “quasi-all-rounder” in one tournament guide (which, in the fine tradition of Pakistan player profiles, also gave him a markedly different birth date than in other publications), Wasim Haider didn’t figure in a single warm-up game yet retained his place in the final squad of 14. If you’ve ever looked at the photos of jubilant Pakistani players circling around the MCG raising the Waterford Crystal trophy and been unable to place one of their faces, Haider is probably your guy.

Imran would at one point label the 1992 tournament the worst organised of all the World Cups, but within the Pakistan camp’s unusual preparation, it could be said that no stone was left unturned. The skipper himself had never felt more motivated for success and in that final configuration of his team-mates it showed; what looked like chaos to outsiders was the beginning of something beautiful.

6. The cult heroes

Everyone has their favourite cult hero of the Cricket World Cup. It’s what sets the tournament apart from all other one-day cricket; have a day out in a far-flung bilateral series and you might become a momentary hero, do it in a World Cup and you’ll live forever. Gus Gilmour, Neil Johnson, Collis King, Eddo Brandes, Winston Davis, John Davison, Dwayne Leverock, Steve Tikolo, Nolan Clarke, Dave Houghton all probably did plenty that was good, but it was their World Cup heroics that keep them at the tip of the tongue for cricket lovers.

For every heroic deed like theirs though, there’s a host of other players whose names evoke warmth despite largely anonymous showings. To those of us enthralled by the 1992 edition, names like Willie Watson, Meryck Pringle, Iqbal Sikander and John Traicos mean far more than they really should. Perhaps then the concept that an international tournament like the World Cup is as much about the joy of participation as it is about winning is something we should remember.

On that note and in the continued interests of this blog presenting opinion as fact, when it comes to cult figures of the World Cup it’s hard to overlook 1987 Australian paceman Andris Karlis ‘Andrew’ Zesers, whose name alone made him a little hard to ignore. Like Graeme Porter eight years earlier, Zesers turned out for his country for the first and final times during the group stages a single World Cup campaign on foreign shores, going wicketless on debut in a loss to India and taking John Wright’s wicket in Australia’s 17-run win over New Zealand.

In truth his backstory is much more interesting than his actual World Cup deeds. Picked as a 17-year-old for South Australia, the son of a Latvian-born construction worker had been the youngest Australian bowler to reach 100 first class wickets but two years after playing his modest role in Australia’s World Cup triumph, a shoulder injury had prematurely ended his career at 23. Every time I look at the photo of the jubilant Australians celebrating their final win - Zesers grinning away anonymously behind Steve Waugh - I can’t help but smile. Was he any good? I don’t even think it matters.

— Guardian News & Media Limited, 2015