The once-catatonic corner of moviedom dedicated to merchandise has suddenly come alive as studios — walloped by vanishing DVD sales and determined to keep fans engaged between sequels — look at themed toys, clothes and home decor with renewed vigour.

And Pam Lifford, president of Warner Bros. Consumer Products, is in many ways leading the charge. “To gain marketshare, it has to come from somewhere,” she said with a mischievous grin, padding in sparkly shoes past a “Hobbit”-themed pinball machine at Warner headquarters here.

Before Lifford joined Warner in January 2016, the studio’s merchandising unit in some years had no growth at all. Last year, profit increased 47 per cent compared with 2015. Revenue from licensed products — Wonder Woman action figures, Harry Potter iPhone cases, Scooby-Doo pyjamas — totalled $6.5 billion, an 8 per cent increase.

Lifford, described by License Global magazine as “savvy, seasoned and supercharged”, credits toy-ready movies that were already in Warner’s pipeline, like the Potter prequel “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them”. Kevin Tsujihara, Warner’s chief executive, credits the way Lifford came in guns blazing.

“I’m confident we can build on the momentum Pam and her team have created,” he said in an email. “It’s a great growth opportunity for the company.”

With the decline in DVD sales speeding up and the box office stalling on a global scale — even as movies become more expensive to make — studios like Warner for the first time are looking to merchandise as an engine.

Film companies will release 25 movies with toy tie-ins this year, according to Bloomberg analysis, up from roughly eight annually in the past. “Jumping headfirst into the space” is how a Sony spokesman described its new approach, which will be on display in July with the release of “The Emoji Movie”.

This summer, stores worldwide will be flooded with items for “Wonder Woman”, “Spider-Man: Homecoming”, “Cars 3”, “Transformers: The Last Knight” and “Despicable Me 3”. Mountains of “Justice League” and “Star Wars: The Last Jedi” paraphernalia will arrive in the fall.

More than ever, consumer products are influencing moviemaking decisions — namely, sequels and more sequels. Retailers are more willing to devote shelf space to tie-in products when there is already proven interest. (Notably, there was almost no merchandise tied to “King Arthur: Legend of the Sword”, which flopped badly for Warner this month.) But how much movie bric-a-brac can the market bear? Some analysts worry that the public will eventually say enough is enough. That happened in 2002, when retailers were stuck with a vast array of “Treasure Planet” items nobody wanted, leading to a Hollywood-wide pushback.

Consumer products can also be a surprisingly fraught business. Some studios have recently found themselves caught in social-media storms involving gender parity — why are some female characters less prevalent in stores than male ones? — and items that overreach, like a “Moana” costume that turned children into tattooed Polynesian warriors.

But the opportunity is too great for studios to pass up, and Exhibit A is Disney. Over the past five years, operating income at Disney’s consumer products and video game business has roughly gone from $1 billion to $2 billion, fuelled by hits like “Frozen”. Disney is the world’s No. 1 licenser, with themed products generating $56.6 billion in retail sales last year.

“Disney does a great job of using consumer products to keep fans energised,” said Anthony DiClemente, an analyst at Nomura Instinet.

It is not a coincidence that Warner, Universal and 20th Century Fox have turned to Disney veterans to invigorate their merchandise divisions.

Lifford spent 12 years at Disney Consumer Products, leaving in 2012, when she was an executive vice-president. Jim Fielding, former president of Disney Stores Worldwide, took over consumer products at Fox in January. Vince Klaseus became Universal’s consumer products and video game chief in 2014 after a long run at Disney.

When Lifford arrived at Warner Bros. Consumer Products, which has about 330 employees worldwide, she was shocked to find that licensing efforts were scattered across 437 shows and films from the studio’s library. “That was not an efficient approach,” she said.

Warner now concentrates on three areas: all things Harry Potter; DC Comics superheroes; and classic cartoons, including Looney Tunes (Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck) and Hanna-Barbara (the Flintstones, Tom and Jerry).

Mindful of increasing upheaval in the retail world, as more consumers move away from traditional stores toward online shopping, Lifford also insisted that Warner become an “active” licenser instead of a “passive” one — the Disney way, which involves extensive retail hand-holding.

“We needed to be curating retail experiences so that each one is special,” she said. “In today’s environment, no one can afford to look the same.”

Lifford sees particular promise in grouping together female DC Comics characters like Wonder Woman, Supergirl, Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy. “I think we can rival princesses with that one,” referring to Disney Princess, a line that annually generates more than $4 billion in sales.

“We love Pam’s hands-on approach and openness to new ideas,” said Cindy Levitt, senior vice-president for merchandise and marketing at Hot Topic, the shopping mall mainstay. “Warner used to have a very traditional approach, and she has really shaken things up.”

The highest-ranking African-American executive at Warner, Lifford grew up in Southern California, where her father owned a small tool business. She studied fashion design at a community college but dropped out to work at a women’s clothing company, eventually going on to work for Nike and Disney.

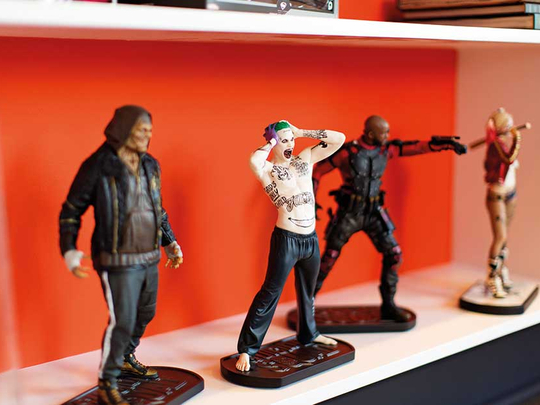

At Warner, which is Hollywood’s largest studio, with vast television, movie and video game operations, the office culture can be sombre and hierarchical. But it is not like that in Lifford’s division, where she had walls painted orange, yellow and teal and brought in pool and foosball tables.

“You’ve got to have fun and let loose now and then,” she said, letting loose a booming laugh. “It gets the creative juices flowing!”