Pakistan and India celebrate the 70th anniversary of their independence from Britain today and tomorrow, respectively. Almost three quarters of a century after these landmark events, the United Kingdom’s foreign policy is undergoing — with Brexit — one of its biggest transformations since decolonisation and the end of British Empire.

Following Brexit, Prime Minister Theresa May has asserted that she wants to rediscover the UK’s heritage “as a great global trading nation”, including with former parts of the Empire and now-Commonwealth, such as India; and other key markets such as China, the United States, and the Gulf Cooperation Council states of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. To this end, UK Secretary of State for International Trade, Liam Fox, has confirmed he is already discussing, informally, new UK trade deals with at least a dozen countries.

At the same time when informal talks have begun with multiple nations on these bilateral trade agendas, Fox has also opened discussions with the 164-strong body of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) over post-Brexit terms of membership. The UK’s current membership is governed by its status within the European Union (EU) with Brussels making commitments on trade tariffs and quotas on behalf of the 28 governments.

Over the next two years of potentially tough negotiations, Fox is seeking to replicate, as much as possible, the UK’s current schedule of WTO commitments. Upon leaving the EU, potentially in 2019, these obligations would serve as the baseline from which the nation would seek to negotiate new trade agreements. While these WTO negotiations contain significant opportunities, they are also fraught with risks. For, if the UK fails to achieve a new schedule of WTO commitments, the nation’s trading arrangements will be severely disrupted, with a proverbial cliffhanger scenario.

A central challenge for Fox with both these potential bilateral trade deals and his WTO agenda is that no agreements can be formally negotiated, let alone finalised, before the UK actually leaves the EU.

Thus, while there has been much fanfare over a potential new UK-US trade deal, for instance, any such agreement could probably not be secured until at least the second half of United States President Donald Trump’s four-year term, when the US administration could have lost much traction in Congress, which would also need to vote on an agreement.

Moreover, while there are key areas ripe for agreement between the two nations in such a pact, including lowering or eliminating tariffs on goods, there are potential disagreements too. This includes over-harmonising financial services regulations, while other possible icebergs lie on the horizon too, not least given the US president’s commitment to “America First”.

Likewise, Fox can only engage in informal talks with other WTO members until a final Brexit deal is in place. Until then, many WTO members are adopting a cautious, wait-and-watch approach to see the exact terms of the UK’s exit arrangements.

Outside of trade, May has re-affirmed that one key area of continuity, post-Brexit, is that the UK will continue to play a major role in international security, including through its membership of Nato. While London will play a genuinely global role through continued membership of forums such as the United Nations Security Council, its continued commitment to Europe will also be very important, going forward. Here, May has sought to emphasise that while the UK is departing the EU, it is not leaving Europe. Instead, she has stressed her desire to continue, if not intensify, cooperation with EU partners in areas including crime, counter-terrorism and foreign affairs.

To this end, the British prime minister wants the UK’s future relationship with the EU to include practical law enforcement partnership and working arrangements, plus those for sharing intelligence, given the apparently growing threat of terrorism across the continent. She has also highlighted that she wants close liaison with EU allies on foreign and defence policies to keep the continent secure, including the prospect of UK military personnel remaining for some time in Eastern Europe, given the perceived threat from an emboldened Russia under President Vladimir Putin.

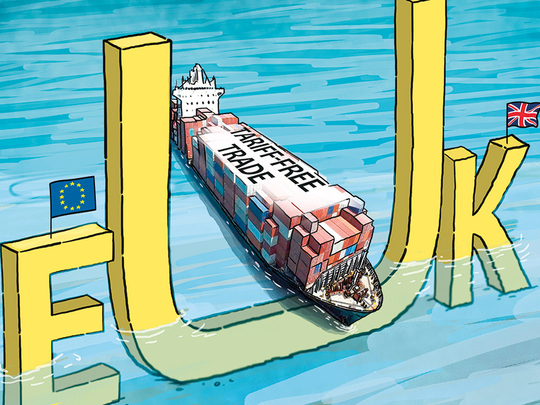

Now that the UK is probably leaving the European Single Market, this potentially extensive web of security and defence relationships would probably be most effective if moulded upon the type of “bold, ambitious, free trade agreement with the EU” with “the freest possible trade on goods and services” that May has set out as one of her key Brexit negotiating objectives. In the prime minister’s own words, this would allow for “tariff-free trade with Europe and cross-border trade that is as frictionless as possible”, while leaving the Common Commercial Policy and no longer being tied to the Common Commercial Tariff, thereby permitting the UK to pursue its own new trade agreements.

At this early stage of negotiations, the EU has not formally commented on post-Brexit security and foreign policy cooperation with the UK. However, it is likely that many national leaders, including those in Germany, France and Eastern Europe will particularly favour a strong working relationship in view of the growing array of external security challenges facing the union.

Indeed, it has been reported that at least one major EU country, Germany, will sign a new post-Brexit bilateral defence cooperation deal in areas including maritime patrol and cybersecurity. Both May and German Chancellor Angela Merkel have not just agreed on the need to show a common front in Eastern Europe, but also internationally too, in the campaign against Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) in Iraq and Syria, where Germany is supplying reconnaissance aircraft, alongside the UK’s bombing missions.

Taken overall, Brexit therefore offers a new opportunity for the UK to reinvent its global role, especially in the context of trade relations. However, it may not be clear until the 2020s to ascertain exactly how successful this agenda will prove to be, given that no new deals can be agreed upon until after Britain leaves the EU.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.