In most dictionaries, a cleric is simply defined as a priest or a religious leader. In ancient times the role of a cleric was a vital one. The role of clerics has been particularly significant in the Christian, Muslim and Jewish civilisations in times past.

From priests to shaikhs, from rabbis to mullahs, theirs was a calling of reading, studying and analysing religious scriptures and presenting them in current day language to their societies.

As the rate of literacy within the societies rose, so did individual interpretation of religious scriptures and significant historical events. Questions were often raised, some which led to the formation of different sects within the same religion. As access to information grew, so also did the number of interpretations, some in direct conflict with each other.

The end of the Twentieth century perhaps signalled the greatest foray into the study of religion by many; individuals who were now enabled by the advent of the internet and the general ease of access to scriptures and manuals in databases from around the world.

In the Saudi society, edicts and fatwas came in bunches, covering diverse subjects from the understanding of the basic pillars of Islam to the correct application of the veil in pursuit of modesty.

As social networking began to take off at the beginning of this century, some preachers and self-appointed guardians of the faith who had previously rejected all forms of modernisation as the work of the devil began to gradually realise the value of this medium in the propagation of their message.

Many began sounding off their own understandings of the Quran and other scriptures and began attracting a great number of like-minded followers. There were those who had the qualifications to do so, as they had been diligent students of religion for years and also had a fair understanding of the role of religion in modern society.

But then there was also another breed. They were the ones using the medium to spread their brand of Islamic interpretations through edicts which were not necessarily substantiated by Islamic scriptures, but more so by traditional mores these individuals were brought up with.

The fact that many of these same people who in the past had dismissed the advent of the internet as the West’s grand design to subjugate the Muslim world was quickly forgotten by them. These so-called clerics with no meaningful religious credibility other than to attract the attention of those with similar inclinations began to take on the media with vigour.

Suddenly the net was flooded with all manners of fatwas or edicts. Some seemed sound and rational while others bordered on the ridiculous. There was a fatwa which called for the separation of the genders to prevent the mingling of the sexes at Islam’s holiest worship site in Makkah by adding extra floors around the Kaaba and dedicating one solely for women.

Another fatwa which defied foundation and drew a lot of ridicule was the one that called for working women to breast feed their male associates at the workplace, thus developing a symbolic bond between unrelated men and women who regularly come into contact with each other and making it permissible for women to mingle with the males there. And then there was the fatwa against women driving.

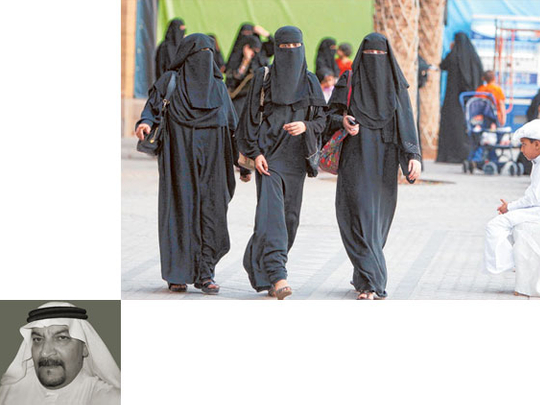

Women have been on the short end of many such edicts. Some of the extreme fatwas may be attributed to hatred towards women, as claimed by some psychologists. These specialists insist that such clerics conceal their venom behind the self-promoted cloak of religious morality.

It is fair to say that many of the outrageous fatwas in recent times have been disguised attacks against the growing empowerment of women in Saudi Arabia.

The recent appointment of 30 women to the Saudi Shura council was greeted by angry self-appointed clerics who crowded the Royal Court to express their discontent. Other such figures followed up their attacks on social media, some going to the extreme of labelling these women as “prostitutes”.

There was never a justifiable religious argument to support their objections; only foggy statements claiming the “specialness” of our society.

The Western media, unable to distinguish the credibility or reception of one fatwa from another began to take notice and react to some of the most outrageous ones, leading to further misunderstandings of Islam. Human rights organisations joined the bandwagon, assuming that these clerics were in fact setting up government policies, especially when it came to the oppression of women.

It came to a point that led the Saudi Islamic Affairs Minister to issue directives that Saudi scholars intending to publish religious edicts (fatwas) on contemporary issues must contact experts at the Ministry of Islamic Affairs or Dar Al Ifta (the Saudi fatwa authority) before releasing their edicts to the public through the media.

The minister pointed out that many of fatwas issued by individuals recently lacked balance or proper study. They were not to publish fatwas except after consulting with other experts. Members of the public were also advised to accept a religious edict only from authentic sources such as the Presidency for Scholastic Research and Religious Edicts (Dar Al Ifta).

That has, however, not stopped many self-styled clerics, who by sporting a beard and a Twitter or Facebook account, continue to release a barrage of their unsubstantiated interpretations, many of which that target the rights of women. The net allows that form of cowardice to continue.

Tariq A. Al Maeena is a Saudi socio-political commentator. He lives in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. You can follow him at www.twitter.com/@talmaeena