Our intercontinental ballistic missiles are on standby... If we push the button, they will blast off and their barrage will turn Washington, the stronghold of American imperialists and the nest of evil... into a sea of fire.”

That is the kind of rhetoric that you might expect from a Dr Evil figure in a Hollywood film. Unfortunately, that threat to incinerate Washington was issued, just last week, by a real person, in a real country, with real nuclear weapons.

The chilling statement by Kang Pyo-yong, North Korea’s deputy defence minister, brought to mind President George W. Bush’s famous pledge that “the United States of America will not permit the world’s most dangerous regimes to threaten us with the world’s most destructive weapons”. Bush’s “axis of evil” speech in 2002 has been widely denounced as the apogee of idiocy — leading to a misbegotten war in Iraq. But, in the light of North Korea’s threat, Bush’s concerns seem rather prescient.

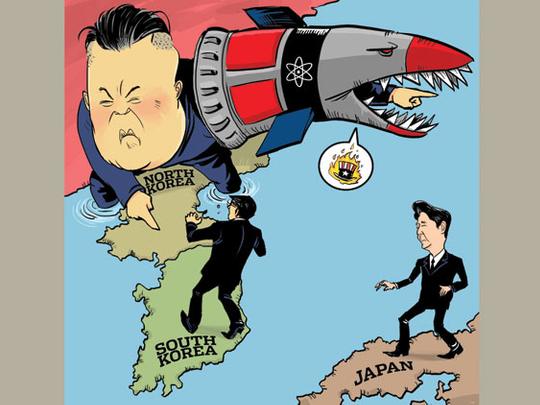

Despite its recent tests of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, few experts think that North Korea is yet capable of hitting the US with a nuclear weapon. But South Korea is clearly at risk, as is Japan. North Korea could also pass nukes on to Iran or to terrorist groups. The North Koreans have sponsored terrorist attacks overseas in the past — and Iranian observers are thought to have been present at the most recent nuclear test.

So it is clear that Bush was identifying a real threat when he linked the dangers of rogue states, weapons of mass destruction and terrorism. The problem is that, 11 years on, no one has found an effective response.

Bush’s own approach — based on armed intervention — failed in Iraq, not least because the weapons did not exist. Barack Obama’s strategy — based on sanctions and diplomacy — is failing in Iran. And China’s approach — based on dialogue and persuasion — is failing in North Korea.

Tacit acknowledgement

It might seem harsh to blame China for the current state of affairs in North Korea. Others — notably the Americans and South Koreans — have had no more success. But North Korea is both a neighbour and a close ally of China, as well as being utterly dependent on Chinese economic largesse. To date, the Chinese have relied on quiet diplomacy. The Global Times, a Chinese newspaper, was peddling the traditional line when it recently declared that the nuclear crisis should be dealt with by “dialogue and negotiations, instead of confrontation”. But China’s decision to back tougher UN sanctions last week is a tacit acknowledgment that this approach has failed.

Behind the diplomatic failure lies a broader problem of strategic vision. China still regards the maintenance of the present regime in North Korea as preferable to the possibility that a reunified Korea would ally with the US. Yet any clear-eyed strategic reassessment in Beijing must surely conclude that the status quo is now more dangerous to China than reunification. The ramping up of North Korea’s nuclear threat may well persuade both South Korea and Japan to develop their own nuclear weapons — starting a nuclear-arms race in China’s neighbourhood.

There is also clearly a growing risk of military skirmishes between North and South Korea, perhaps in the next few weeks. And there must also be a chance that the North Korean regime will ultimately use its weapons — unleashing a nuclear war, just 800km from Beijing.

Many in the west are calling on China to force change, by choking the economic life out of the North Korean regime. China could do it. But any such action would undermine the logic of mutually assured destruction that traditionally keeps the peace between nuclear powers.

Faced with the prospect of its own imminent collapse, the North Korean regime might no longer be deterred from using nuclear weapons. Certainly, a regime that has been prepared to see millions of its own people starve or die in labour camps is unlikely to be frightened by the prospect of mass civilian deaths.

That has led to some making the alternative suggestion that the outside world should offer a security guarantee to North Korea — guaranteeing the regime’s survival, in return for nuclear disarmament. But such a policy would be both immoral (given the regime’s murderous nature) and ineffective. No outside power could guarantee the survival of the Kim regime.

And, anyway, the North Koreans seem to have concluded — following the fall of Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi — that it would be suicide to give up their nuclear weapons.

The only thing that could definitively remove the North Korean nuclear threat would be regime change. But the point at which the regime was toppling would also be the moment of maximum danger that it would use nuclear weapons.

Faced with so many dangers and dead-ends, the Americans and the Chinese need to think together about the most threatening scenarios. The Americans will have contingency plans to try to seize and secure North Korean nuclear weapons, in the event of a catastrophic breakdown of order. Perhaps it is time that they discussed those plans with the Chinese — and maybe even developed them jointly. The idea of a joint Chinese-American operation to deal with North Korea’s nukes sounds like another Hollywood movie. But, then again, so does the idea of a North Korean Dr Evil threatening to incinerate the US.

— Financial Times