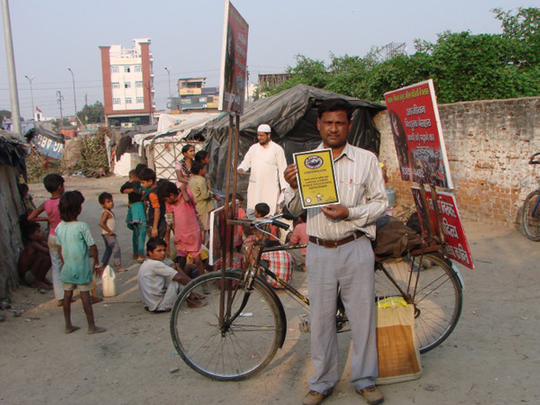

Lucknow: Every day, Aditya Kumar cycles around 64km with a heavy load of books and his few possessions on the back of his battered old bike to bring education to India’s slum children.

The science graduate has dedicated his life to teaching in the slums of Lucknow, a sprawling city in northern India that is home to some of the country’s most deprived communities.

He takes no money for his lessons, which he gives all over the city, parking his bike wherever he is needed and staging an impromptu outdoor lesson.

“These children do not know what a classroom looks like. Until I met them, they had no reason to visit a school,” Kumar said during one of his lessons, gesturing to a group of rapt-looking pupils.

A Right to Education Act passed in 2009 guarantees state schooling for children from six to 14 in India.

But education activists say schools are often overcrowded or inaccessible, or that the quality of teaching is so poor that children simply stop going.

Poverty is also a major driver, with India being home to the largest number of child labourers in the world.

Kumar, who does not know his exact age but thinks he is in his mid-40s, has been conducting his mobile school for around two decades, with no fixed curriculum and no standard textbooks.

Most of his pupils are under 10 and have no education at all.

Practical learning

He teaches them functional English and mathematics, with the aim of getting them to a standard where they can start going to a regular school.

“I can relate to the lives of these kids. I know how tough life can be for want of an education,” says Kumar.

As the son of a poor labourer who wanted his children in paid work as soon as they were able, Kumar had to fight to go to school.

He managed to find a place in a government-run establishment, but he ran away from home when he was a teenager because his parents insisted he stop studying and start earning his keep.

For a while, he lived on the streets, before meeting a teacher who spotted his potential and helped him graduate from university in science.

In return, Kumar helped his new mentor with his teaching — and found his vocation in the process.

He has no teaching qualifications, however, and says he never had any ambition to become a proper schoolteacher.

He believes he can make more of an impact on literacy through his mobile school, which he says reaches around 200 children a day.

Government figures show that around 97 per cent of children of primary school age are in education, but campaigners say the true figure is far lower.

Many of those who do attend classes are failing to learn the basics, according to a major, annual survey of schoolchildren in rural areas released in January.

Dismal figures

Only one quarter of children aged eight could read a textbook meant for seven year olds, the survey of 570,000 students found.

“Overall, the situation with basic reading continues to be extremely disheartening in India,” the survey, by Indian education research group Pratham, concluded.

Kumar’s solo efforts are applauded by child rights activists, including teacher Roop Rekha Verma who said it was “no mean feat” teaching from a bike.

“I am so glad that his efforts have exposed so many underprivileged children to the world of words,” the former vice-chancellor of the University of Lucknow said.

“And with this exposure these children now have a reason to attempt accessing newspapers and books,” she said.

But she stressed that much more needed to be done to help India’s millions of impoverished children facing bleak futures receive an education.

To earn money, Kumar occasionally undertakes paid tuition for private students. But mostly he lives on charitable donations, sleeping on the streets like many of his pupils.

When Limca — the makers of a soft drink that publishes India’s answer to the Guinness Book of Records — wanted to honour him for his work in 2014, the certificate had to be mailed to a well-wisher as Kumar has no fixed address.

“I am used to it,” he said. “I have learnt the art of surviving.”