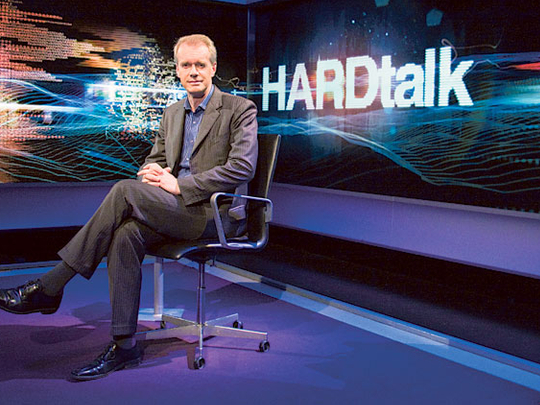

Stephen Sackur is a man who needs no introduction on how to conduct an interview. The presenter of BBC’s flagship interview programme, “HARDtalk”, has interrogated everyone from heads of states to famous entertainers and business leaders. “People say to me what the key is to a good interview,” he told Weekend Review. “And I will say, actually, the success of an interview has in some way been decided before we even start recording, because if I don’t have the right research, knowledge and background in detail, I can’t dig deep enough to make it a good ‘HARDtalk’.”

My interview with Sackur took place at the BBC’s office in Shepherd’s Bush, London. Prior to our meeting, I had spoken to Sackur on the phone, and he had suggested it would be a good idea to come in at the time of the recording of his programme. At the reception I was taken by a producer to a small room which had a TV set tuned in to ‘HARDtalk’, which was about to begin recording in a few minutes. As I waited I had an interesting chat with the make-up woman, who started complaining to me about some heavy bags she had to bring in from the shop that day. As I looked around the room I could see pictures of well-known personalities on the wall, including Prime Minister David Cameron, former prime minister Gordon Brown and Hollywood actor Antonio Banderas. Suddenly Sackur appeared and, after a brief chat and a visit to the makeup room, he disappeared to do the show.

The guest on the show that day was Bahraini human rights campaigner Mariam Al Khawaja. I watched the recording as she and Sackur talked about protests in Bahrain, accusations of double standards and sectarianism. “There are certain regions around the world where we have more impact than others,” Sackur later told me. “I am glad to say that across the Gulf region we still have a big impact because a lot of people obviously speak very good English there. And almost everybody has satellite or cable TV and has access to BBC World News — and we cover the Middle East in some detail.”

The recording for the interview lasted more than 30 minutes, after which we went to Sackur’s office. For such a personality on BBC, I was surprised to find that his room was non-extravagant, with a desk and some files and a copy of “Nowhere Home” by Carlos Acosta. Sackur had gone to get some tea and while he was away on the door to his room I spotted a sticker with the numbers “0666”. When he returned, he explained “HARDtalk” is moving offices and apparently had these stickers all over the place. On the wall behind him was a quotation by Rachel Naomi Ramen on the importance of listening — something Sackur clearly has to do a lot of as presenter for “HARDtalk”.

I began the interview by asking Sackur the story of how he came to work for the BBC. “I wanted to be a journalist since my childhood,” he said. His career started when he was 17 years old, working with a local newspaper in Yorkshire, in the north of England, with a circulation of about 4000. Later he attended Cambridge and Harvard, after which he joined the BBC, initially as trainee producer. But as he worked with other reporters on documentaries and projects Sackur realised he fancied the idea of being in front of the microphone and not behind the scenes.

Yet it wasn’t easy switching from being a producer to a journalist. So he left the BBC to work freelance for radio programmes and to write for newspapers such as The Guardian and The Telegraph before being invited back to work at the BBC as a foreign correspondent.

An important break came in 1991, when Saddam Hussain invaded Kuwait. Sackur covered the first Gulf War and became very much involved in the post-invasion story there.

After the war, a series of his essays were published as a book called “On the Basra Road” by the London Review of Books. It was based on his experience of the British army. Sackur had spent eight weeks with the British troops in action. For most of the time nothing much was happening because the war was largely fought in the air, with the ground war lasting only about 72 hours.

“At the end of it, my unit of British forces came across this huge convoy of vehicles which had been bombed by the Americans; they were trying to escape from Kuwait city on the road to Basra. I wrote about it,” he said. “And I wrote about the ethics of war — so many people had been killed even when it was clear that Saddam Hussain and his forces had been defeated.”

At first it wasn’t clear who these people were because their convoy was burnt and bombed to a point where you could not identify the individuals. “But it was clear to me that many of the people on this convoy were civilians and were not even Iraqis,” Sackur said. “Many of them were guest workers who had been forced to stay by the Iraqi troops, and who were fleeing as the Iraqis fled Kuwait city and got stuck in this convoy which was destroyed.” His work caused a stir at the time and was chosen as one of the books of the year by Spectator magazine.

Another major achievement was interviewing US president Bill Clinton in an airbase in Germany. “It was during the Balkans war,” he said. “The Americans had eventually decided that there should be a military campaign against Milosevic. So that was a very strictly controlled interview where I was only interviewing him about the Balkans and about the US military involvement in the former Yugoslavia. And I was only given a few minutes with him.”

Then in July 2001, as the BBC’s Washington correspondent, he interviewed Clinton’s successor, George Bush. Meeting president Bush in the White House was quite an experience for Sackur because of all of the minders, press people and protocol. “It is a very controlled environment,” he said. “You are given a very short time. And if you go one minute over, you have the White House press team looking at their watches and making gestures with their fingers. The press team in the White House is perhaps the most heavy-duty operation I have ever seen.”

At the time Bush was about to go on his first trip to Europe. “We in Europe did not know what to make of this president,” Sackur said. “He was new and was perhaps underestimated in Europe, in the sense that he was seen as the guy who got the job partly because of his family name. He was seen as a guy who was not interested in many of the issues the Europeans were interested in, including environmental issues. Some people called him the toxic Texan. And so it was a chance for me to try and get an impression of the man. But of course everything changed on 9/11. Whatever president George W. Bush might have been, everything changed on that day. And we cannot know what sort of president he would have been had it not been for the attack on 9/11.”

In that interview Sackur discussed global warming, views on Tony Blair and the missile defence controversy with Russia. Noticeably absent was any mention of Afghanistan. “It is interesting to look back at that interview and to consider that before 9/11 terrorism and Afghanistan were not the top issues on the agenda,” he said. “They only became top issues after 9/11.”

After this rather interesting experience, he spent three years as a correspondent in Brussels. By now Sackur had reported from different corners of the world including Europe, Washington and the Middle East. “My children were growing up and I was beginning to think perhaps it was time I moved back to the UK,” he said. At the same time Tim Sebastian, who was leaving “HARDtalk” as the presenter, asked Sackur out of the blue if he wanted do a few episodes just to see if he liked it. “I really enjoyed it,” he said. “It really suited me. As soon as I sat on the ‘HARDtalk’ chair I actually felt that this was a job I could actually do and that I would enjoy doing. And luckily for me, they agreed that I could do it. And so I was offered the job, and I took it.”

Sebastian had been well known for confrontational style of interviewing. Did Sackur find him a difficult act to follow? “Well, I think what I felt was it would be a big mistake to try to copy Tim Sebastian,” he said. “You know he has a unique style, a unique look. For a start he has a moustache and I don’t. You know there are lots of ways in which we are different people. And I think the trick to being successful on television is to be comfortable in your own skin, not to try to be something that you are not, but to try to bring out the best of your own personality and your own journalistic ability. I probably would agree that I am perhaps a little less overtly confrontational, a little less aggressive on screen, but I hope that my argument, my use of facts, my use of the evidence, is just as challenging and rigorous and just as able to put the guest on the spot as Tim’s was.”

Since taking on the role of presenter one of the difficult interviews he did was with former US vice-president Al Gore in Oslo in 2007, after he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his campaign on climate change and for the film “An Inconvenient Truth”. “Prickly” and “defensive” is how Sackur described him. “In the course of the interview, when I challenged some of his claims in the film, and some of the things that have been said by him and other campaigners, he began to accuse me and the BBC of having a clear agenda to damage the climate change campaign and him in particular as though it was personal,” he said. “Of course, it wasn’t personal. I had no agenda. I was just trying to ask interesting and important questions. So the more personal it became for Gore, the more difficult it was to keep this interview going. It became bad-tempered.”

Another one of Sackur’s more prominent interviews was with former Pakistani president Pervez Musharraf in November last year. While some guests have been intimidated being in the “HARDtalk” seat, others such as Musharraf actually appeared to relish engaging in a verbal combat with Sackur. “I think he quite enjoyed it,” Sackur said. “You can divide leaders and top politicians into two categories when it comes to “HARDtalk”. There are those who resent my constant questioning and my refusal to let issues go. And there are others, and I would say Musharraf was probably one of them, who enjoy the sense of combat.” Sackur feels ego might also have something to do with it. “There are quite a lot of powerful politicians with big egos,” he said. “I think they — both women as well as men — regard it as something of a badge of honour to come on ‘HARDtalk’ and show Stephen Sackur who is the boss.”

Another combative interviewee was President Hugo Chavez in Venezuela. “He doesn’t do many interviews but he finally agreed to see ‘HARDtalk’,” recalled Sackur. “Once we got into the room with him in his presidential palace, he was so up for it. His adrenaline was flowing, he couldn’t stop talking, he kept waging his finger at me, he became furious, but also he was enjoying it. And in fact, the US presidents, Chavez couldn’t stop talking. We had 45 minutes with him. We had to edit it down because it was too much. We only have 25 minutes. But he just wanted to keep going and win the argument.”

Sackur started laughing as he described his meeting with the Venezuelan leader. “Chavez is one of my best memories because he was so fully engaged,” he explained. “Sometimes ,frankly, you meet politicians who are going through the motions, who are so rehearsed in their answers and so determined not to answer the question that you have asked but to answer the question they wished you had asked that the interview itself can become very formulaic — very dry and for the audience very dull. But if a politician really engages and sort of forgets that it something that he wants to control but instead regards it as a genuine exchange of views then it can be very exciting.”

I read out to Sackur a quote of Sir David Frost, critiquing the aggressive style of interviewing by some presenters: “You have to get people to open up, not shut up. It’s all about the testing quality and the intellect of the question, not the style.” What is Sackur opinion on it? “Well, he is absolutely right,” he says. All I would say is, I don’t regard it as my job to be aggressive. I don’t regard going in and doing ‘HARDtalk’ as entering a boxing ring. And I don’t hold the view that for me to win is what the interview is about. In fact it is not about winning and losing at all. It is about extracting the right kind of information.”

Sackur spoke with admiration about Frost for the immense amount of research he did in his famous interviews with president Richard Nixon. “He talked to Nixon for hours and he produced some of the best interviews that we have ever seen in the age of television,” he said. “So David Frost is an extremely talented guy but obviously in a long career his style has developed, along with his desire to entertain. I mean, the kind of interviews ‘HARDtalk’ does can be entertaining. But entertainment isn’t their only purpose.”

I mentioned Julian Assange, the WikiLeaks founder who presents an interview show on Russia Today, to Sackur. “You have to judge somebody by the company they keep to a certain extent,” Sackur said. “And I have talked about the reputation that we have built up over many years on ‘HARDtalk’, and we carefully guard our reputation, and we regard it as very important. Personally I can’t take very seriously an interview show which is aired on a media platform which is owned by the Russian state, which claims to be challenging rigorous questioning of power. Because I am not sure the Russian state is very open about how it exercises power, and I think if Julian Assange was serious about his desire to question power in all its forms, he would find it very difficult to take this money from a Russian state media organisation.”

It is interesting to note some of the differences between Sackur and Assange, as both have interviewed guests such as Imran Khan and Noam Chomsky. “To be absolutely fair and honest I haven’t watched Julian Assange’s programmes, but from what he said about his programmes, I think there is an inclination to interview people with whom he has some sympathy or can at least find some common ground with,” Sackur said. “I mean my aim isn’t to find common ground, my aim is to keep myself out of it. I don’t want to have opinions — I want to have the intelligence to ask the right questions. I repeat, I haven’t watched the programme, but Julian Assange is a highly opinionated person. And I think his interview style is perhaps more an exchange where he is an active participant, where his opinions count for something. Whereas I don’t think my opinions count for anything. What matters for me is my ability to ask the right questions. I am not there to express my opinion or my sympathy with anybody.”

Sackur is also apparently not a big fan of another well-known TV presenter who replaced Larry King on CNN last year. “If you were to ask me today about the interviews I see on TV,” he said, “I’d say the best example of what ‘HARDtalk’ is not is probably the Piers Morgan show on CNN. Because mostly Piers Morgan, it seems to me, has an ambition to entertain but not much else. And I think a lot of people are on his show on the understanding that they won’t be vigorously tested.”

While Sackur has interviewed some of the biggest names in the world of politics for ‘HARDtalk’, notably missing are two controversial former leaders — George Bush and Tony Blair. When can we expect them on the show? “Both are on our list and every so often we approach their offices and say, ‘Is now the time?’” Sackur said. “They are very difficult. I just interviewed a former prosecutor from the International Criminal Court, and there are many people around the world who want to see Bush and Blair answer the most challenging questions about their involvement, for example, in the Iraq war. And both of them, I think, are aware that a programme such as ‘HARDtalk’ would ask them very tough questions about their decision-making on the Iraq war, and that may be one reason why neither of them wants to do ‘HARDtalk’ right now.”

Syed Hamad Ali is a writer based in London.