Virtually everywhere you turn across the African continent, there is a significant Japanese presence.

Might these be investments by Hitachi for electronics production facilities? By Sumitomo for banking networks? By Asahi for breweries? Or by Komatsu for equipment assembly plants?

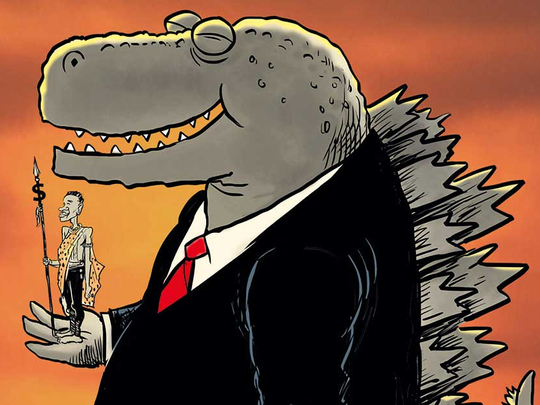

No; they are the legions of Japanese automobiles driven by Africans in their rapidly growing megacities as the continent’s urbanisation accelerates. As China and India increasingly shape the Asian footprint of business investment in Africa — exploiting precious first mover advantages along the way — Japan remains in the back seat.

It wasn’t always this way.

With the 1993 launch of the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD), Japan was the first large Asian country out of the gate to recognise the importance of African-Asian economic relations. Held every three to five years since then, it was only in 2000, when China commenced its triennial Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), that others in Asia began to catch on to Japan’s early recognition of the promise African economic development held for Asia’s own growth prospects.

India soon followed China’s footsteps, and in 2010 it began to hold India-Africa Business Forum Summits. Today, both the China and India summits are “must-attend” events by African political and business leaders, and participation is extensive.

Of course, the real story about the nature of the pace and position of each player in the African-Asian economic race lies less in how many such gatherings take place or who attends them, and more in what is the level of real cross-border commerce and resource flows taking place. Here, Japan has significantly fallen behind the pack.

While Japanese business leaders, eager to get in on the African game, have started to persuade Tokyo to pick up the pace, to date, however, the majority of Japan’s resource flows to Africa continue to be focused on development assistance rather than on commercial investment by Japan’s private sector.

China and India, on the other hand, have shifted significantly away from development assistance as the focus of their involvement in Africa. Beyond their sizeable investments in the continent’s natural resource development, they have increasingly concentrated on commercially-related activities in the construction of roads, railways, harbours and other facets of infrastructure, as well as in finance, retailing, education and medicine.

So what explains Japan’s tepid involvement in Africa? Over much of the past decade-and-a-half one reason can be found in Japan’s unduly inward focus as a result of the slow pace of domestic economic growth. Why “unduly”?

Because when economic policymakers keen on jump-starting growth do not find conditions at home ripe for such an outcome, the best policy stance is to not retrench but rather to expand abroad and tap into fast growing markets.

It is particularly poignant in this particular case because it was precisely over the last decade-and-a-half when much of Africa’s growth rates accelerated to new highs: average annual GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa was greater than 5 per cent over this period. While in the past few years parts of the continent slowed due to declines in commodity prices, a comeback is now starting. But Tokyo still seems poised to be taking too myopic a stance toward Africa.

While lower prices are driven in part by several supply-side factors, such as new North American oil and gas coming on stream and Saudi Arabia’s strategy of maintaining its large-scale production flows, there is little question that a key element to the story is decreasing demand in China, owing to the fact that its own economy is decelerating.

As a consequence, there are increasing reports from the field that Chinese investment in Africa has begun to stall (although systematic data assessing this phenomenon are lacking).

If true, does this not actually present a potential opportunity for the Japanese to now raise their game on the continent, taking advantage of China’s misfortunes? Japan would certainly benefit from increased access to African oil. And in the case of non-oil minerals, investing in Africa would enhance the diversification of Japan’s supply; for example, about three-fourths of Japan’s copper supplies currently are imported from Latin America.

Africans, in parallel, can gain much from a renewed effort by Japanese firms to increase their investment in the region. Some of the continent’s most critical needs, such as development of basic transport infrastructure; electric power generation and distribution; heavy industry; construction equipment; and machinery manufacturing are areas where Japan excels and thus significant contributions to Africa’s growth can be made.

But it is development of the services sectors — including finance, banking and trading; logistics and shipping; and education and health care — that in the long run will likely hold the key to the international competitiveness of Africa (as well as of most emerging markets around the world). In fact, to the surprise of most observers, cumulative foreign direct investment inflows in Africa’s services sectors have begun to actually outstrip that in either the industrial or agricultural sectors. Of course, it’s the services sectors where Japan has a strong comparative advantage relative to other Asian investors in Africa. Indeed, in contrast to China, where most expatriates living in Africa are unskilled or semi-skilled workers and believed to number one million, Japan’s expatriates in Africa are mostly skilled or highly skilled and amount to only about 100,000.

Together with the fact that Japanese firms operating abroad evidence a strong record for sharing of know-how and technology transfer, this could well help fill, in part, Africa’s human capital gap. And, as the ageing of Japan’s population continues to increase and thus its workforce shrinks, Japan has every incentive to move in this direction.

With sustained growth in Japan continuing to be elusive, isn’t it time for Japan to focus more on Africa?

The writer is CEO and Managing Partner of Proa Global Partners LLC, an emerging markets investment transaction advisory firm, and a faculty member at Johns Hopkins University.