Dubai: Pakistani businessman Abdul Sattar Pardesi came to Dubai intending to stay a year or so during which he would run a small general trading shop.

He ended up staying 44 years.

“I was thinking what every new arrival was thinking: make some money, don’t spend it, and take it home. There wasn’t much else to do here those days,” says Pardesi, now 67.

Pardesi grew fond of the city and its people, and the fact that business was growing didn’t hurt either. However, back then, in 1970, it was a simple life with few luxuries, he said.

“When I got here, there was no UAE. January 24, 1970 was my first day in Dubai.”

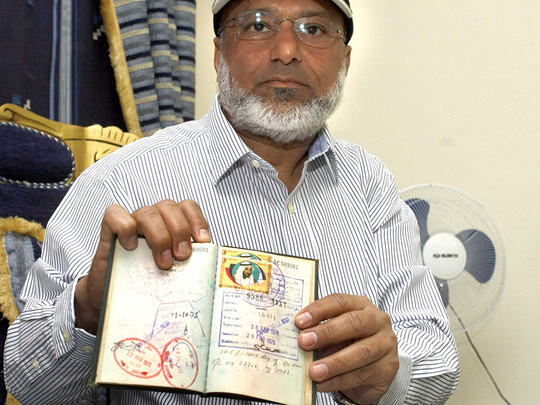

The UAE, then known as the Trucial States, gained independence from British rule in late 1971. Pardesi is among a small group of expatriates who experienced the colonial administration in the UAE. “Even my first visa was actually issued in Karachi by the British ‘for and behalf of the Rulers of the Trucial States’. It’s like a piece of history that I’ve kept with my first passport,” he said. “My Dubai-issued visa in 1973 was only for one year.”

Also in Pardesi’s possession are handwritten documents of his company’s trade licence.

“In 1975, the then Ruler of Dubai allowed us to form a limited liability company without a local sponsor. I still have that exemption. I want to thank the previous and current leadership for allowing me this continued facility. You cannot get something like that today, it’s very rare.”

Pardesi said he continued his father’s “honest and hard work ethic” to gradually build a Dh80-million corporate group.

It all started humbly. His father had arrived in the UAE in 1964 when basic facilities such as air conditioning were a status symbol, Pardesi said.

“When I got here, my lifestyle was of a labour camp standard. Ninety-five per cent of people [expatriate population] in Dubai were bachelors. We read newspapers that were a week old, after they got here from home by ship,” he added.

“There were no sports, no TV or radio in English, no fancy restaurants. The biggest thing to do entertainment-wise was see the open-air cinema on Fridays.”

Phone calls, even letters, were not common.

He added: “We used to get telegrams when there was important news from back home. I remember people used to fear a loved one had passed away if someone said ‘a telegram has come in for you.’

“You could make a trunk call, after requesting the operator. They would send someone to collect the money for the call a day or two later. There was no billing system.”

Pardesi said when he looks back at the years gone by, he still has to come to grips with the UAE’s transformation.

“This is a desert. All what you see here today – of the fruit markets selling fresh imports, the tigers in zoos, the glamorous skyscrapers, the perfect roads, and modern services – is supposed to be impossible for this kind of climate. But the leadership made it possible.”

Pardesi said “this was a place people came to reluctantly, if nothing worked out back home. Now people from the West are flocking here. It’s because there was, and is, a vision for excellence, which is being fulfilled.”

However, there is a place in Dubai that “has not changed one bit. It’s the creek. You still have the abra boats and the old buildings lining the creek, the small fish in the water. It even smells as I remember it when I first landed on shore as a young man.”