Malaysia Airlines’ two crashes in less than five months are sending tremors through the aviation insurance market — not least because the carrier’s $2.25 billion (Dh8.26 billion) overall liability policy is mysteriously missing a standard clause that usually limits insurers’ payments for search-and-rescue costs. The looming payments are coming as underwriters face other claims, because of the shelling of Libya’s main airport a week ago, with 20 planes damaged, and a pair of deadly Taliban attacks on Karachi’s airport in Pakistan.

For just one category of aviation insurance — war-risk insurance on the planes — claims for incidents in the past five months total an estimated $600 million for a sector that collects $65 million a year in premiums.

Airlines have many insurance policies. But the main one is an “all risk” policy that covers most crash-related expenses, including what is usually the biggest: paying for settlements with passengers’ next of kin. Malaysia Airlines’ broader policy has a high cap by industry standards — $2.25 billion for each crash — because the carrier operates big Airbus A380s, each configured for 494 passengers, and it wanted ample coverage.

But the policy is unusual in that it does not have a separate limit for search-and-rescue costs — it is limited only by the overall $2.25 billion cap for the policy, three people with knowledge of the policy said. It is unclear why the clause was omitted, they said.

The absence of a separate limit for search-and-rescue costs means that Malaysia Airlines could seek reimbursement for tens of millions — and potentially hundreds of millions — of dollars in search costs if the Malaysian and Australian governments decide to bill the airline for even part of their considerable expenses in looking for Flight 370, which vanished March 8.

An Australian delegation has been sent to Malaysia to broach the question of sharing costs for the Flight 370 investigation and seeking insurance reimbursement, said people with knowledge of the visit and the insurance policy, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

By tradition, governments do not seek reimbursement from an airline for search-and-rescue costs. As a result, the airlines do not typically need to ask their insurers to cover these costs; the insurers cover only so-called commercial costs, although their contracts do allow governments to seek reimbursement.

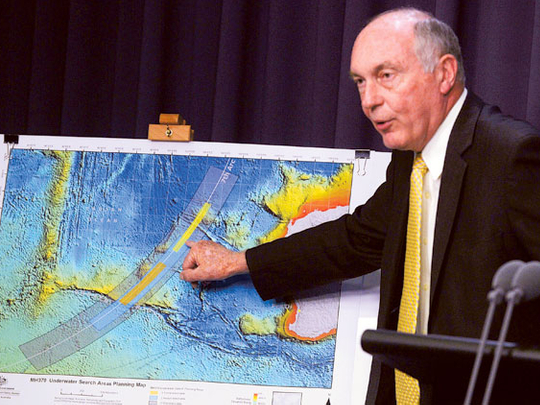

In the case of Flight 370, the Australian government is paying A$8 million, or $7.5 million, to commercial contractors for a survey of the floor of the Indian Ocean and has set aside another A$60 million to hire a contractor to tow deep-sea submersibles across 23,000 square miles to look for the missing plane.

Australian officials, Malaysian officials and the lead underwriter of the broad liability policy, Allianz of Germany, declined to comment, as did the broker who negotiated the insurance policy on Malaysia Airlines’ behalf, the London-based Willis Group Holdings.

War-risk insurance market

The crash of Flight 17 in Ukraine appears to have caught the war-risk insurance market particularly by surprise. Insurers often prohibit airlines from flying across dangerous areas, or cancel their policies, but most carriers kept flying over Ukraine until the crash.

The number of flights there dropped only 12 per cent in the month leading up to it. “One assumes that if the war-risk underwriters thought there was any risk, they would have prohibited airlines from flying or cancelled their policies,” said Paul Hayes, head of accidents and insurance at Ascend, an aviation consulting firm in London.

Malaysia Airlines’ war-risk policy has a separate, much lower limit than the overall policy for claims for search-and-rescue costs. As in most aviation insurance contracts, a provision caps claims for these costs to a small percentage of the overall value of the policy.

The Atrium Underwriting Group, the lead underwriter for Malaysia Airlines’ war-risk insurance, said in a statement that it had immediately approved payment for the loss of the aircraft in Flight 17.

Aon, a London-based company that is one of the world’s largest insurance brokers, said over the weekend that the plane had been insured for $97.3 million, but Atrium did not confirm the value.

The crash of Flight 370 triggered a half-payment from Atrium under the war-risk policy after adjusters concluded that there was a substantial but not ironclad case that the crash may have involved pilot suicide or other criminal action. War-risk policies also cover deliberate, malicious acts.

The Allianz-led policy — Allianz itself has only 9 per cent of the exposure, having reinsured the rest with other underwriters — paid the balance of the cost of that aircraft, which had been insured for $100.2 million, insurance executives said. Insurance adjusters agreed with the Malaysian government there was a strong but not fully proved possibility that Flight 370 was lost because of deliberate action, given that the plane made at least four turns over the course of an hour before heading south across the Indian Ocean and apparently running out of fuel.

The final compromise followed a precedent in other cases in which pilot suicide was suspected but not proved. “It was basically split between the two policies,” said Neil Smith, the head of underwriting at the Lloyd’s Market Association, a trade group composed of Lloyd’s of London insurance underwriters.

The crashes of Flight 370 and Flight 17 are not Malaysia Airlines’ first unusual insurance claims, however. The airline had an unusual claim in 2000 for the loss of an Airbus A330 travelling on the same route as Flight 370 but in the opposite direction.

In that case, a canister of a mysterious Chinese shipment destined for Iran broke open near the end of a trip from Beijing to Kuala Lumpur and began leaking, producing a smell that prompted the captain to conduct an emergency evacuation upon landing of all 266 people aboard.

A subsequent investigation found that the hold was contaminated beyond cleaning with mercury and other chemicals that may have been precursors for the manufacture of nerve gas. The Malaysian government ended up digging a large hole in the ground near the airport tarmac and burying the plane.

Insurers paid a full settlement of $90 million.

Airline insurance premiums are set through an annual process in which underwriters bid for which provider will offer the lowest premiums at the best terms.

Few airlines’ policies have been renewed yet; Malaysia Airlines’ has not. Until this year, Malaysia Airlines paid some of the lowest insurance premiums in the global aviation market, because it had a fairly young fleet of Boeing and Airbus planes.

Many leases and other contracts in the airline industry require carriers to be insured. Despite recent losses, Smith said, airlines were still able to obtain insurance, although he declined to speculate on the likelihood of increases in premiums.

“If it wasn’t available,” he said, “the airlines wouldn’t be able to fly.”

— New York Times News Service