Minneapolis: It was a friendship that began in high school and ended in militancy.

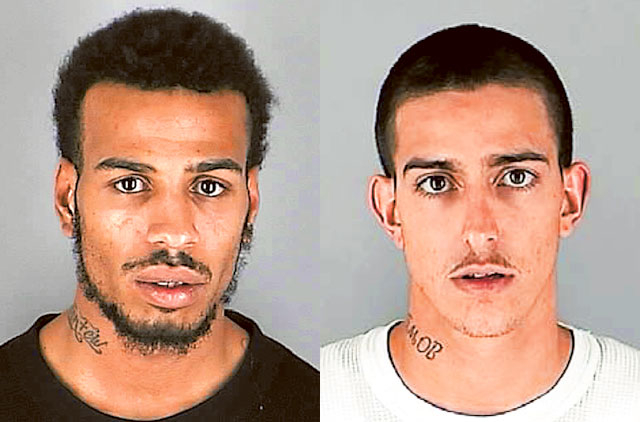

As Minnesota teenagers growing up in the 1990s, Troy Kastigar and Douglas McAuthur McCain shared almost everything. They played pickup basketball on neighbourhood courts, wrote freewheeling raps in each other’s bedrooms and posed together for snapshots, a skinny white young man with close-cropped hair locking his arm around his African-American friend with a shadow of a moustache.

They walked parallel paths to trouble, never graduating from high school and racking up arrests. They converted to Islam around the same time and exalted their new faith to family and friends, declaring that they had found truth and certainty. One after the other, both men abandoned their American lives for distant battlefields.

“This is the real Disneyland,” Kastigar said with a grin in a video shot after he joined Islamist militants in Somalia in late 2008. McCain wrote on Twitter this past June, after he left the United States to fight with the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant, “I’m with the brothers now.”

Cedar Avenue in the Cedar-Riverside district. Leaders in the Somali community say they are losing a battle to keep new waves of young men and women from turning to the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Isil).

Today, both are dead. While their lives ended five years and over 2,000 miles apart, their intertwined journeys toward militancy offer a sharp example of how the allure of Islamist extremism has evolved, enticing similar pools of troubled, pliable young Americans to conflicts in different parts of the world. The tools of online propaganda and shadowy networks of facilitators that once beckoned Kastigar and Somali men to the Horn of Africa are now drawing hundreds of Europeans and about a dozen known Americans to fight with Isil, according to American law enforcement and counterterrorism officials.

“Troy and Doug fit together in some ways,” Kastigar’s mother, Julie Boada, said at her home here. “They’re both converted Muslims. They both have had struggles.” She added, “They’re connected through that.”

Investigators are looking into what led a handful of other people from Minnesota to follow the same path, said Kyle Loven, an FBI spokesman in Minneapolis. American intelligence and counter-terrorism officials say McCain, 33, and a second American believed to have been killed while fighting for Isil travelled in the same circles in Minneapolis and knew each other.

Officials still have not publicly confirmed the identity of that man, but he has widely been reported to be a Somali immigrant in his late 20s who went by at least two names, calling himself Abdirahmaan Muhumed on his Facebook page. He spent much of his life around Minneapolis, worked at the airport over several years and ended up in Syria this year, declaring in a text message to a friend, “With out jihad there is no islam.”

Pathway for recruits

To law enforcement officials and community leaders here, the pathway for many recruits remains murky and difficult to uncover, but the latest wave of volunteers is a chilling replay of recent history. Beginning in 2007, over 20 men, mostly of Somali origin, left Minnesota to join the Shabab militants who seized territory across Somalia and besieged the capital, Mogadishu.

The radicalisation of the men prompted federal investigations and brought enormous scrutiny to the Somali population in Minneapolis, the largest in America. (Estimates put Minnesota’s Somali population around 30,000.) As Shabab forces withdrew from Mogadishu under pressure from African forces supported by the United States, people here held anti-Shabab rallies, and prosecutors eventually won convictions against eight local men on charges stemming from the flow of money and recruits to the militants.

But now, leaders in the Somali community say they worry they are losing a battle to keep another round of young people from turning to another Internet-savvy and brutal group, Isil. Community leaders say several families have reported that their children have vanished.

“We need to open our eyes,” said Ahmad Hirsi, a banker who has led youth groups in the Twin Cities. “This is not going to stop.”

Officials say Isil is not specifically targeting Somalis but is instead using social media, chat rooms and jihadist forums to recruit men and women susceptible to its message — a target audience that includes Somalis in Minneapolis. Community activists and a friend said one Somali was Muhumed, whom they described as a mostly secular man in his late 20s or early 30s whose family had emigrated from Mogadishu. He always seemed more interested in working out and basketball than in religion, acquaintances said.

“He would talk about LeBron James and Kobe Bryant, and then, the next thing you know — pfft! — he’s gone,” Hirsi said.

Farhan Abdullahi Hussein said he had met Muhumed when they worked at the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport. Patrick Hogan, an airport spokesman, said a man named Abdifatah Ahmed, an alias Muhumed had used, had worked there on and off from November 2001 until May 2011, refuelling planes and cleaning. (Shirwa Ahmed, an ethnic Somali who blew himself up in a suicide bombing in Somalia in October 2008, also had a job at the airport, pushing passengers in wheelchairs.)

‘My best friend’

Hussein, who described Muhumed as “my best friend,” said Muhumed used to fume about violence in Libya and Gaza, asking, “Is this fair?” Muhumed dreamed of joining the Ogaden National Liberation Front, a rebel group trying to carve out an independent state in Ethiopia for ethnic Somalis. When he drank, Hussein said, Muhumed’s anger boiled up. Once, at a shopping centre popular with Somalis, he even punched a community advocate named Abdi Abdulle who had spoken out against the group’s violent tactics.

Abdirahmaan Muhumed is widely reported to be the second American killed while fighting for Isil. He dreamed of joining the Ogaden National Liberation Front. “He always wanted to be a freedom fighter,” Hussein said. “He always wanted to be a hero.”

In April, Muhumed sent Hussein a text message saying jihad was his path now. “God gave us jihad,” he wrote. On July 8, he sent a short message celebrating the Islamic holy month. It was the last Hussein heard from him.

McCain and Kastigar grew up in a different world from the towering apartment complexes and rows of Somali barbershops and restaurants that were a backdrop for Muhumed’s life. But they found a passion for Islam and, ultimately, a path to militancy.

Traces of the friendship between Kastigar and McCain are bound up in a few photo albums in Boada’s home. In one, they wear nearly identical plaid shirts. This is how relatives say they want to remember them: Kastigar as an energetic, open-minded boy who climbed up walls, and McCain as someone who made music and fiercely loved his younger sister, Lele.

“They had a similar sense of humour,” Boada said of the men. In his teenage years, Kastigar began drinking, smoking marijuana and failing classes, and Boada said she had seen “a sadness and a darkness” settle over him. He dropped out of high school, got his equivalency diploma and worked at a mortgage office or cutting hair. But he was often unemployed. And a series of arrests compounded his troubles finding work, Boada said.

McCain, whose family moved from Chicago when he was young, attended Robbinsdale Cooper High School with Kastigar until 1999, then switched to Robbinsdale Armstrong High for a year, the district said. He never graduated. Court records show he was arrested several times, for driving violations, theft and a marijuana charge.

While both men converted to Islam around 2004, it is unclear whether one man’s religious decisions steered the other’s. Hatim Bilal, a high school friend who comes from a Muslim family, said Kastigar had told him that Bilal’s family and the cohesion among Bilal’s brothers inspired him to convert. A spark returned to Kastigar’s eyes after he discovered his new faith, his mother said.

“They just wanted to be a part of something,” said. Bilal, who knew both men but was close to Kastigar. “They were just trying to find something that just accepted them for who they were.”

But problems persisted. Kastigar was crestfallen when, after training to become an X-ray technician, he was told that his criminal history would make it difficult for him to get a job in the field.

In 2008, Kastigar told his mother that he was going to Kenya to study the Quran. He bought a one-way ticket and left that November. He spoke with Boada five times, telling her that he was eating well and helping people. He was killed in September 2009 at age 28.

Kastigar’s death may have shaken McCain, friends and relatives said. Around 2009, McCain moved to San Diego, where he had relatives and worked at a Somali restaurant, according to a cousin, Don Urbina. He enrolled at San Diego City College, a college spokesman said. Urbina said the family was shocked at his decision to join a jihadist group that has beheaded two American journalists and massacred thousands of Syrians and Iraqis.

Alicia Adams, a high school friend of McCain’s who last spoke to him in 2013, said his faith was “such a small piece of who he was,” adding, “He was still Doug.” But Urbina described his cousin as “very serious about God.”

“His mother doesn’t know how it got to this point,” he said. “None of us really want to know.”

Boada said she still did not know exactly how her son had ended up in Somalia, hoisting an assault rifle and wearing a checkered head scarf. She said he had never been motivated by hate, but by a belief that somehow he could be a hero. Sometimes, she said, people will ask her about his death. But more often than not, she does not discuss it.

“I just don’t tell people,” she said. “I just say that my son passed away in 2009. If someone asks why, I just say, ‘It was a tragedy.’ ”