The day after the 2016 election, Conor Oberst called his old friend Michael Stipe from R.E.M. for condolence.

“He’s someone I look up to as a voice of reason,” Oberst said. “He was torn up about it all, but good to talk to. He said that now’s the time to find more resolve than ever to donate to Planned Parenthood and all the institutions that we’re going to have to rely on.”

The two had performed, with Bruce Springsteen, on the Vote for Change tour in 2004, hoping to rally support for John Kerry’s ultimately unsuccessful presidential campaign. That was the last time the singer-songwriter felt so despondent about American politics. Until November, that is.

“I think this is worse,” Oberst said of the election of Donald Trump as president. “But I felt more freaked out in ‘04. Maybe because I was younger and less cynical.”

People like to joke that at least the protest music will be good in the Trump era. Right now, though, it’s hard to imagine dancing. But for fans around the 36-year-old Oberst’s age, listening to his older music now can stir up those same feelings of being young, outraged and despondent about politics. His new music might be even more harrowing.

Bright Eyes’ 2005 album I’m Wide Awake, It’s Morning was lauded for its 10 songs of immaculate, articulate folk-rock that will probably stand as Oberst’s lasting achievement. It had moments of shuddering fury, but for many fans, it brought a quiet dignity to what felt like total helplessness in the face of an election loss. They were afraid that the Iraq war would never end, that gay marriage was impossible, that America had re-elected (by an even greater margin than before) a president who to many seemed a distillation of America’s darkest tendencies.

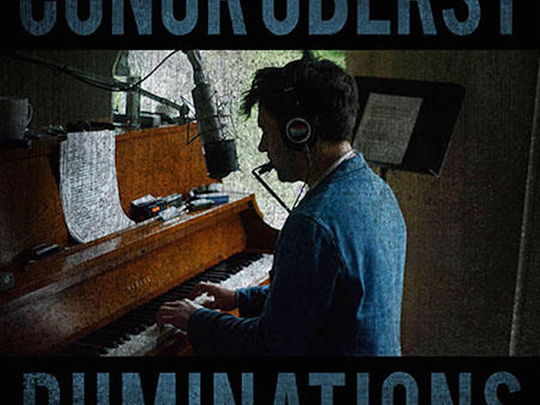

I went to see Oberst last month at Immanuel Presbyterian Church in Koreatown. He played a few solo dates to support his new album, Ruminations, which has earned comparisons to Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska for being a minimalist, almost demo-quality recording that nonetheless captures a bleak mood of its own. It’s spare and harrowing in a way we haven’t heard from Oberst since he was a quivery 19-year-old, spinning gothic folk tales from his frigid corner of the Midwest.

But mostly, I went because Oberst’s voice had walked me through my last bout of dark thoughts after a presidential election, and for the first time in a long time, I felt like I needed it again.

Vignettes

Oberst had one of the few good protest songs of the George W. Bush era. I still remember seeing Oberst perform When the President Talks to God in an outsize cowboy hat on The Tonight Show With Jay Leno, and thinking that somewhere, an FBI file was being hastily assembled.

“At the time, we felt like we had to do something,” Oberst said. “I was nervous when we did the [stage] blocking, and started to freak out. I was just wearing a hoodie, and I thought, ‘No, I need a cowboy suit, something to hide inside where if you were just flipping through the channels in the South, you’d think, “Hmm, he looks like a nice lad.’”

But even in protest, his music at the time of Wide Awake was graceful. It was richer and more personal than much more overtly protest music usually is. It wasn’t just railing at bad policy; it was 10 vignettes of feeling utterly lost and packing up and moving to a place where you felt more wanted.

A great comfort

For me, that was LA for Oberst, it was New York. To this day, few records better capture the transcendence and loneliness that comes from being young and starting anew. Flasks on the subway after dark; protest marches that did nothing but meant everything; a dawning of how big and terrifying the world was, but also how rare and valuable your refuges were in the midst of it all.

“Music is unique because it can get behind enemy lines and affect people,” Oberst said. “Some kid in Utah can get his hands on a Clash record and be introduced to whole new ideas, and that’s still a powerful thing.”

At the Koreatown show, hearing Oberst’s voice singing Lua again, in the dead silence of an actual sanctuary, was both a great comfort and almost a cruel joke. All that work of the last eight years to make the world more just, and now we’re right back here again.

Even before this, Obersthad a very rough few years, dealing with a since-retracted accusation of sexual assault and a brain cyst.

I don’t know what the new era of protest music will sound like. I know it will be black, it will be Latino, it will be Muslim and indigenous and it will be done by women and members of the LGBT community. These are the people with much to lose in Trump’s America, and they should be listened to with moral authority now.

The best artists making protest music today — Beyonce, Kendrick Lamar — use the personal to catalyse the political. Insisting on the validity of your life and emotions in the face of it is an act of bravery.

“I don’t know what Trump means for art,” Oberst said, “but art does thrive in adversarial times, so hopefully, people will continue that.”

Stumbling out of that church after Oberst’s performance, I was reminded that protest music isn’t necessarily about affecting change or fixing things. Making music at all can be an act of defiance, if just to say that you existed and felt this way at a specific time, in spite of every reason to despair and stay quiet.

“Go listen to The Future by Leonard Cohen,” Oberst said. “It sums up the dark side of my perspective and it pretty much envisions Trump’s America: ‘Give me crack and... sex, take the only tree that’s left... I’ve seen the future, brother. It is murder.’”