Masanori Fukuoka remembers the first time he was moved by art. “I must have been ten or 12 years old. It was a rainy day in Japan and it was at my house. I remember seeing this big spider’s web. In the centre was a huge black and yellow spider. I don’t like spiders. But I was fascinated. The sky was grey, it was rainy and the gardens were green. There were hundreds of dewdrops on the web and in the centre was this spider. I couldn’t move. It was a very uncomfortable feeling, to see such a huge web and at the same time, those beautiful raindrops.

“That experience, of having two contradictory feelings at the same time, is what I get from Jogen Chowdhury’s work. Now I can say it’s vibrant and sensitive, but at the time it was why I bought his work,” the affable Japanese collector says, talking to GN Focus at Sovereign, the new Dubai gallery that’s had the expatriate Indian community abuzz since its launch earlier this year.

Fukuoka, whose family is in the fish processing business, has the largest collection of work by Chowdhury, with more than 400 of his drawings and paintings, and is probably the single biggest collector of post-independent Indian art with works by M.F. Husain, Ram Kumar, Tyeb Mehta, F.N. Souza, V.S. Gaitonde and other household names in his collection. About 5,000 of these are housed in his Glenbarra Art Museum, near Osaka, where 80 to 100 are on display at any point. Fukuoka owns a lot more, but refuses to say how many.

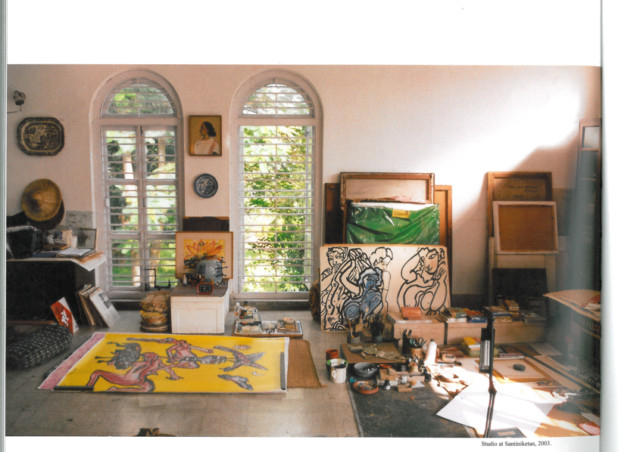

Chowdhury, of course, is one of India’s greatest living artists. At 74, he still does new work and will bring several of his latest pieces to Dubai in October, for a solo exhibition at Sovereign. A total of 30 pieces will be on display and sale at the Jumeirah Lakes Towers gallery from October 2 to 31, spanning five decades of his career.

“Jogen has evolved a distinct language of his own, and the stages of development in this language will be clearly visible at our exhibition,” says Sovereign owner Dadiba Pundole. His Mumbai gallery has been associated with the artist for more than 30 years. “Jogen belongs to what I term the second generation of modern Indian artists, and is one of its most important voices. Buyers for his work are not limited to the Indian diaspora; he appeals to both East and West,” he adds.

It was Pundole, now a close friend of both Chowdhury and Fukuoka, who got the latter started on collecting the former’s work. “Dadiba told me, ‘Just buy’,” Fukuoka says. Pundole’s only explanation — now — is that he believed in Chowdhury. The story exemplifies the sort of trust the art buyer has in the gallerist; Pundole’s convictions paid off substantially.

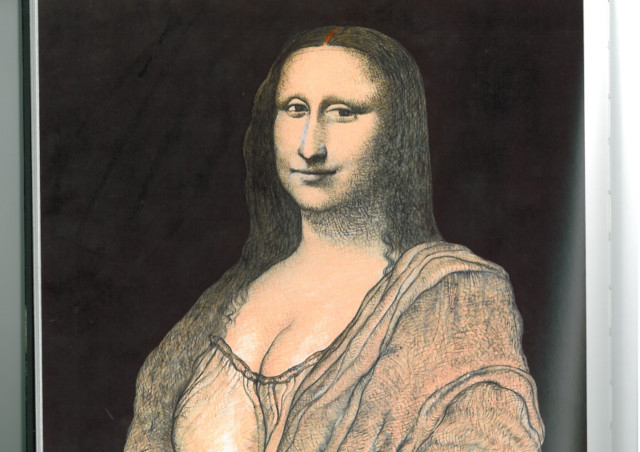

Chowdhury’s work sells for millions of dirhams. His 1979 ink and pastel composition, Day Dreaming — a fine illustration of his distinctive fluid lines and simple forms defined by crosshatching — sold for a record $609,629 (about Dh2.2 million) in 2009, after a furious bidding war.

Fukuoka will not put a price on his collection — either whole or in part. “I’m not a dealer, I’m a collector. I haven’t thought about investment,” he says. “[Years after] I bought, the price went up. I started seriously collecting Indian art in 1990, maybe the price went up in 2002, 2004.”

First travelling to India in the seventies because of an interest in Buddhism, which he studied at university, Fukuoka became a regular visitor. He was soon buying Indian art as souvenirs, but didn’t become a serious collector until he clashed with >

his father on the costs. “I had some art from Bali, Singapore and Holland. But I didn’t have any from India, which was a shame because I thought I knew India. And instead of buying a few, I bought 40 or 50. I was shocked; the price was so cheap. I felt it was unfair and couldn’t understand it. At the time, I thought maybe I could introduce Indian art to Japan,” he says. “But over the first decade, there were always arguments with my father, who wanted me to stop buying. My mother, in between us, told me to do what I believed in.”

So he took her advice, befriended the artists, bought more work, set up a museum in one wing of his factory, invited the artsy crowd around and even put out a book. By 1998, once liberalisation had spawned its first batch of millionaires, the Indian art world was in a flap: who was this Japanese man buying up all these suddenly desirable artworks? Fukuoka was persuaded to bring the works to India to display them in the country of their origin, in Mumbai, Bangalore and Kolkata.

That was a turning point of sorts, he says. “Until then, I had a motive… my collection was more than what I wanted, partly to show and introduce art to people. From then on, I’d have my own works, what I liked. I’d collect eight or ten artists, about 10 works each.

“I wanted to get to know some of these artists; when you have more of one artist, you feel you know the artist,” he says.

Given that his efforts buoyed prices for several painters — he acquired Tyeb Mehta’s triptych, Celebrations at a New York auction in 2002 for a record Rs 1.5 crore (about Dh 894,000) — he now found himself in the position of having to sell bits of his collection to buy strategic pieces.

“To have good works, I have to sell and then buy,” Fukuoka says. “Some of them I puzzled over — why did I buy these?”

Among those whose work he has bought since is Chowdhury, whose pre-liberalisation work really appeals to him. He says art created today appears borderless and it’s often impossible to tell whether the artist is Japanese, Chinese, American or Indian. “But when I see work from the sixties and seventies, I feel something. So I have Husain from the sixties, Ram Kumar and Gaitonde from the seventies and Jogen from the seventies and eighties.”

But why does he buy art at all? “It’s like a human being,” he tells me after much probing. “You have a different reason for liking different art. Some people may be nice and sweet, some people you admire and respect. Certain artists, I like to buy to know their work. Jogen’s work I want to know — just to read books about it are not enough. Art by different artists resonates differently.”

Now that he’s buying art for himself again, he says the next step is to build a museum close to his house where he can enjoy these paintings with his favourite music. “I want to be able to walk to the museum in my pyjamas,” he smiles. As he learnt early, art is best enjoyed in the home.