When you enter Dilnavaz Mehta’s third-floor apartment in central Mumbai, the sounds of the city’s famed bustle begin to fade away and the sights and memories of another era come alive as you segue into a world of nabobs and Hindoos, thugs and nautch, or dancing, girls.

Mehta, ever willing to talk about the provenance of the thousands of old prints stacked in the room, will take you deeper into the period between the late 18th and 19th centuries. This was the peak of the British reign in India, till the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 rang the first warning signal for the British empire. Photography had not yet become widespread and paintings and prints were the only means of showing a curious British populace the many wonders of the exotic East.

In the early years, travellers drew rough sketches on the spot, then returned to England, where they sat with a professional artist to recreate their memories. It was only a matter of time before the professional made his entry. Francis Swain Ward, an officer of the Madras Artillery, was the first trained artist to come to India. A full-time soldier who arrived in 1757 and travelled with the army, he was the first to make on-the-spot drawings of India’s many monuments. After him came the deluge — a procession of artists who spent decades immortalising the exotic landscapes and peoples of India.

The Daniells — Thomas and William, uncle and nephew — are the best known of these artists. Thomas was a professional engraver as well, which accounts for the quality of their prints. The duo came to India in 1786 and their first work was Views of Calcutta. Their magnum opus was Oriental Scenery — a massive effort divided into six parts, each containing 24 plates of their paintings. (Some of their paintings can be viewed in Kolkata’s Victoria Memorial today.)

Then there was the adventurer Captain Robert Melville Grindlay, who sailed to India in 1803. If the name rings a bell, well, a travel advisory firm and money exchange service he set up is what later came to be known as the ANZ Grindlay’s bank. A series of 36 aquatints titled Scenery, Costumes and Architecture is one of his best-known works.

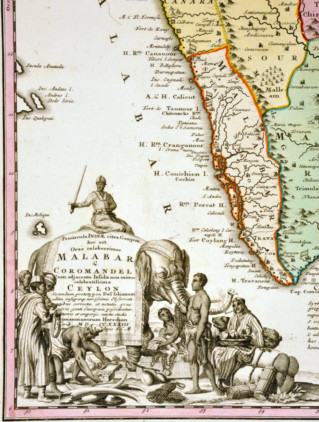

Many artists were also commissioned to make detailed maps, often the first of a particular region, to document the lands under the control of the empire. James Rennell, who went on to become surveyor general of Bengal, is believed to be the first to draw an accurate map of the whole of India as it then existed.

Engravings of these paintings were made to produce limited edition prints, each of which was considered a work of art. Since colour printing had yet to come in, the prints were coloured by hand. Engravings were the most popular method of reproduction; other methods were etchings, lithographs and aquatints.

These prints were sold in loose sheets or bound in volumes that were, as Mehta points out, “The precursor to the coffee-table books of today.”

And thus was born a new art form that not only continues to fascinate but has emerged as an invaluable record of a bygone era. In these yellowing sheets, we can see monuments in their original glory, costumes and headgear that look familiar yet quaint, landscapes of the heart of Mumbai that show it looking like the tropical island it once was.

The etchings also introduced a new painting style to India, which traditionally favoured formal portraiture.

If you love antiques but find them pricey, if you like art but find it even pricier, these charming prints could give you a lot of pleasure on a far lower budget: prices start as low as Rs3,000 (about Dh198). If you are looking for a good investment, and can afford a couple of lakhs, Mehta will even manage a portfolio for you.

“If you keep it well, a print will appreciate steadily in value and not fluctuate the way paintings or stocks might,” says Mehta. How much of an appreciation could one expect every year? “It’s difficult to generalise, but on an average, you could say 10 to 15 per cent, though it could go up as high as 200 per cent,” she says.

However, she advises clients to buy pieces they like. “It can’t be just about money; you also have to derive pleasure from it. So I give clients a choice and tell them to pick what their heart chooses,” she reveals.

Other tips: Pick blue-chips (well-known artists); they’re always a safe bet. Buy prints in good condition; fungus-ridden pictures could endanger your other pieces. (Restoration is possible but expensive.) And always buy from a well-established dealer.

Mehta, who has quite a few buyers from Dubai and the Gulf region, laughs, “There’s one client from Abu Dhabi who always buys in bulk and I’m sure he sells them at a mark-up. But it doesn’t matter so long as I get my price.” And that’s precisely the attitude you should adopt whether you buy for pleasure or profit or both. As she says, it’s not just about the money.