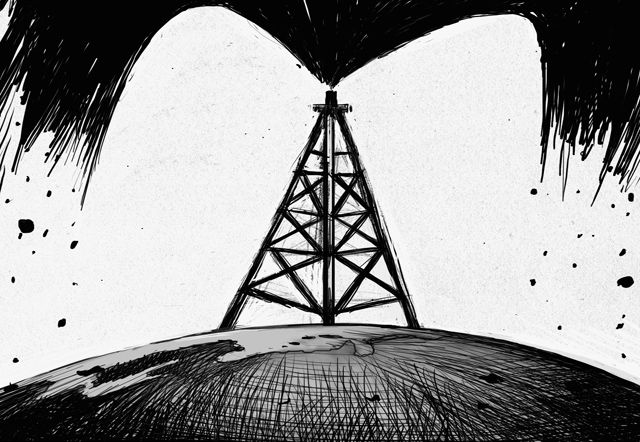

Crude is still being discovered; existing fields are not being exploited to the full. So it's hard to predict the exact point at which the world's dwindling reserves will precipitate a crisis. But it's coming. Massive new oil finds off the southern states of America and Brazil plus exciting discoveries in currently non-producing countries such as Ghana and Uganda sit uneasily with claims the world is running out of crude.

BP recently boasted about a "giant" strike on the Tiber field in the Gulf of Mexico and BG, the former exploration arm of British Gas, talked of its "supergiant" at the Guar prospect off South America, yet critics argue they cannot make up for the fast depletion of existing fields.

These "peak oil" believers say the high point of oil output could even have passed already. They argue it will take 10 years to develop the likes of Tiber while a string of similar discoveries would have to be made at very regular intervals to move the peak point back towards 2030 the projection used in some scenarios put forward by the International Energy Agency.

The debate has intensified in recent weeks after whistleblowers claimed the IEA figures were unreliable and subject to political manipulation, something the agency categorically denies. But the subject of oil reserves touches not just energy and climate change policy but the wider economic scene, because hydrocarbons still oil the wheels of international trade.

Even the Paris-based IEA admits the world still needs to find the equivalent of four new Saudi Arabias to feed increasing demand at a time when the depletion rate in old fields of the North Sea and other major producing areas is running at seven per cent year on year.

Deep concerns

"The fields which are producing today are going to significantly decline. We are very worried about these trends," says Fatih Birol, the chief economist at the IEA, who has gradually ramped that depletion figure upwards and has expressed deep concerns at a huge fall-off in the current levels of investment in the sector.

Birol and the wider industry are well aware the days of "easy" oil are over. The big global companies are struggling to find enough new oil to replace their exploited reserves year-on-year and Shell found itself on the end of a major fine for exaggerating its reserves report to the Securities and Exchange Commission in the US.

The energy groups used to rely on the easily exploited shallow waters in the Gulf of Mexico, politically friendly areas of the Middle East and geologically simple reservoirs off Britain to feed their refineries and petrol stations. But as these wells begin to run dry, Big Oil is being forced into ever more physically or politically demanding areas to bring home the crude at much greater financial cost.

The Tiber find is just one example. There may be as many as four billion barrels of oil in place but the hydrocarbons are located in 4,100 feet of water, which makes them very expensive to extract.

Peter Odell, professor emeritus of international energy studies at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, but with close links to Opec (Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries), says the new finds really are highly significant.

"It shows the industry is capable of finding more oil than it uses and shows we have not come to any peak."

But that is not accounting for politics and the rise of the "resource nationalism" that has made the multinationals persona non grata in some of the great oil-bearing regions. Developing countries such as Venezuela, Nigeria and Russia have increasingly been moving down the road to self-reliance, developing their own state-owned firms at the expense of the international players.

The western firms see part of their salvation coming from being able to enter markets from which they have previously been barred, such as Iraq. But, leaving aside continuing questions about physical safety, both BP and Exxon have signed deals there in recent weeks on terms so tight they would have been inconceivable only a few years ago.

Increasingly, Big Oil is also moving into environmentally sensitive areas that put it in collision with environmentalists, such as the Barents Sea off Norway, the waters around Alaska and if it can get its hands on it the Arctic itself.

In the meantime, the oil companies have moved into all sorts of "unconventional" projects such as "gas-to-liquids" (converting natural gas into petrol and diesel) and, most controversially, the tar sands of western Canada. The Athabasca sands being developed by Shell and others in Alberta are a number one hate target for Greenpeace and the new breed of socially responsible investment funds run by the Co-op and others. They could hold reserves of 170 billion barrels, making Canada number two behind Saudi Arabia, but are only considered commercially viable if the crude price remains above at least $50 a barrel.

Demand growing

The IEA predicted in the just-published 2009 World Energy Outlook oil demand would grow from 85 million barrels a day today to 88 million in 2015 and reach 105 million in 2030. The organisation presumes the challenge of meeting that demand can equally be met with a mixture of higher Opec production and considerably more output from unconventional sources.

These assumptions became the centre of an explosive debate three weeks ago after the Guardian spoke to IEA insiders who expressed deep concerns about the methodology and "politicisation" of the figures. Some senior figures are unhappy about what they see as over-optimistic forecasts coming out of the agency which represents the interests of 28 consumer countries, particularly the US.